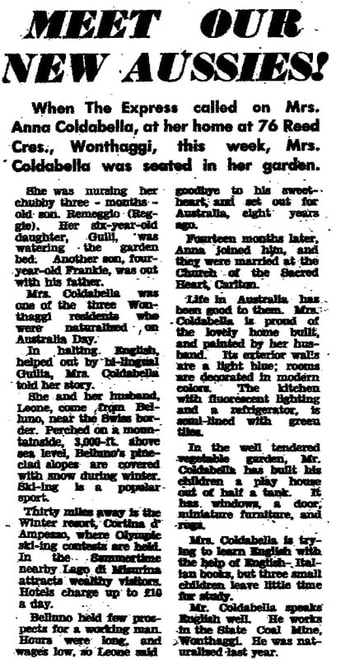

In January 1958, the Powlett Express interviewed Wonthaggi’s Anna Coldebella, who had just become a naturalised Australian. Fifty-five years later, almost to the day, Anna’s son fills in the back story about her early years in Wonthaggi.

The Express, January 28, 1958

The Express, January 28, 1958 By Frank Coldebella

ANNA Melchioretto, one of eight children – two girls, six brothers – arrived in Melbourne in May 1950. She had left her family in Italy, not expecting to see them again. Back then, to emigrate was almost like dying – nobody returned.

She married Leone Coldebella in Carlton. They lived in a shed in Mine Road, Kilcunda, next door to Luigi Coldebella, her husband’s uncle, who had come to Australia in the 1920s. Kilcunda was known as Dago Valley. Other families there included the Mabilias, the Marsiglios and Anna’s cousins, the Grisottos and Piasentes.

Life in her new country was lonely for Anna at first – the men worked long hours in the mines, six days a week, to pay off fares and build a future for their families. She missed the vibrancy of extended family and neighbours that characterise compact rural village life in Italy. Nor was she used to such hot summers and such big snakes.

Six months after she arrived, the Kilcunda mine closed and they moved to what is now Sanderson Street. They shared a four-room cottage with two other families. The only water tap was in the front yard. The water wasn’t as good as the alpine stream that ran through their home villages but it didn’t freeze in winter. Once the new settlers had cleared the blackberries, they established gardens, built chook pens – it was handy being near the tip – made jam and bottled fruit.

Like most Italians, from the Angaranes to the Zotties, my parents had inherited a peasant ethic of working from daylight till dark. In the evenings when my father was on afternoon shift, which meant getting home at 11pm, my mother would sit with her feet on the edge of the coal stove oven, meditatively knitting, sewing and rereading letters from family.

After the evening meal in summer, we might do a giro around the neighbourhood or suburb. People walked a lot then, to the shops, mines, school, theatre, dances. There were no fat people. There were few cars and still the odd horse and cart, as well as house cows and goats tethered on unmowed nature strips and vacant lots. On someone’s advice, we might detour along a lane to admire someone’s beans or corn or sample overhanging fruit or berries.

One of my earliest memories is of walking along the crescents and down Hagelthorn Street, which was predominately Italian. Most houses were close to the road, where it was easy to engage with passers-by. You could smell the produce on the stove or tomatoes being boiled down to paste. My parents talked to other Italians sitting on their verandahs, knitting or sewing. The kids played marbles in the street and there would be the sound of a piano, accordion or bagpipes from somewhere.

My mother recalls that, apart from Hagelthorn Street, summer evenings in Wonthaggi were so quiet it seemed as though there had been a death in every house. Undoubtedly some were camping at the beach a few kilometres away, between Harmers and the river. Some of the old-timers who were born in tents on diggings up north took every chance to cook on a campfire.

The postman came twice a day, blowing a whistle with each delivery. I’d often be asked to go and see if there were any letters. Letters from Europe were pure gold – read and reread, every syllable a tiny thread of connection to home. Letters were written with pen and ink on thin paper. We loved the colourful stamps, a contrast to Australia’s which featured Queen Elizabeth’s head in a range of colours.

Some Italians returned to Italy, unable to cope with a resentful minority who believed Italians took jobs from true-blue Aussies but for those who had survived the hunger, deprivations and horror of war Australia was paradise enough.

My mother was in Jack Phillips grocery store one day with two young kids. Seeing her situation, the Anglo man in overalls who was in front of her let her get served first. Later she learned he was the mayor of the town, Jim Longstaff. In Wonthaggi, the hierarchy was based on co-operation, not competition.

In 1966 she returned to Italy to find that it, too, had prospered and changed. People dressed fashionably and consumed conspicuously. The bush mountain paths were overgrown – they were no longer tramped by gatherers of mushrooms and berries.

In Europe, all the art, history, culture, religion and faith in leaders had not stopped the Fascists from bringing death and misery to millions. In Wonthaggi it was ordinary people who got things done and the mayor wore overalls to the grocer’s shop.

It was time for Anna to become an Australian citizen.

Anna Coldebella still lives at 76 Reed Crescent, in the house where she and Leone raised their family. Four of her five children have houses in the same street.

ANNA Melchioretto, one of eight children – two girls, six brothers – arrived in Melbourne in May 1950. She had left her family in Italy, not expecting to see them again. Back then, to emigrate was almost like dying – nobody returned.

She married Leone Coldebella in Carlton. They lived in a shed in Mine Road, Kilcunda, next door to Luigi Coldebella, her husband’s uncle, who had come to Australia in the 1920s. Kilcunda was known as Dago Valley. Other families there included the Mabilias, the Marsiglios and Anna’s cousins, the Grisottos and Piasentes.

Life in her new country was lonely for Anna at first – the men worked long hours in the mines, six days a week, to pay off fares and build a future for their families. She missed the vibrancy of extended family and neighbours that characterise compact rural village life in Italy. Nor was she used to such hot summers and such big snakes.

Six months after she arrived, the Kilcunda mine closed and they moved to what is now Sanderson Street. They shared a four-room cottage with two other families. The only water tap was in the front yard. The water wasn’t as good as the alpine stream that ran through their home villages but it didn’t freeze in winter. Once the new settlers had cleared the blackberries, they established gardens, built chook pens – it was handy being near the tip – made jam and bottled fruit.

Like most Italians, from the Angaranes to the Zotties, my parents had inherited a peasant ethic of working from daylight till dark. In the evenings when my father was on afternoon shift, which meant getting home at 11pm, my mother would sit with her feet on the edge of the coal stove oven, meditatively knitting, sewing and rereading letters from family.

After the evening meal in summer, we might do a giro around the neighbourhood or suburb. People walked a lot then, to the shops, mines, school, theatre, dances. There were no fat people. There were few cars and still the odd horse and cart, as well as house cows and goats tethered on unmowed nature strips and vacant lots. On someone’s advice, we might detour along a lane to admire someone’s beans or corn or sample overhanging fruit or berries.

One of my earliest memories is of walking along the crescents and down Hagelthorn Street, which was predominately Italian. Most houses were close to the road, where it was easy to engage with passers-by. You could smell the produce on the stove or tomatoes being boiled down to paste. My parents talked to other Italians sitting on their verandahs, knitting or sewing. The kids played marbles in the street and there would be the sound of a piano, accordion or bagpipes from somewhere.

My mother recalls that, apart from Hagelthorn Street, summer evenings in Wonthaggi were so quiet it seemed as though there had been a death in every house. Undoubtedly some were camping at the beach a few kilometres away, between Harmers and the river. Some of the old-timers who were born in tents on diggings up north took every chance to cook on a campfire.

The postman came twice a day, blowing a whistle with each delivery. I’d often be asked to go and see if there were any letters. Letters from Europe were pure gold – read and reread, every syllable a tiny thread of connection to home. Letters were written with pen and ink on thin paper. We loved the colourful stamps, a contrast to Australia’s which featured Queen Elizabeth’s head in a range of colours.

Some Italians returned to Italy, unable to cope with a resentful minority who believed Italians took jobs from true-blue Aussies but for those who had survived the hunger, deprivations and horror of war Australia was paradise enough.

My mother was in Jack Phillips grocery store one day with two young kids. Seeing her situation, the Anglo man in overalls who was in front of her let her get served first. Later she learned he was the mayor of the town, Jim Longstaff. In Wonthaggi, the hierarchy was based on co-operation, not competition.

In 1966 she returned to Italy to find that it, too, had prospered and changed. People dressed fashionably and consumed conspicuously. The bush mountain paths were overgrown – they were no longer tramped by gatherers of mushrooms and berries.

In Europe, all the art, history, culture, religion and faith in leaders had not stopped the Fascists from bringing death and misery to millions. In Wonthaggi it was ordinary people who got things done and the mayor wore overalls to the grocer’s shop.

It was time for Anna to become an Australian citizen.

Anna Coldebella still lives at 76 Reed Crescent, in the house where she and Leone raised their family. Four of her five children have houses in the same street.