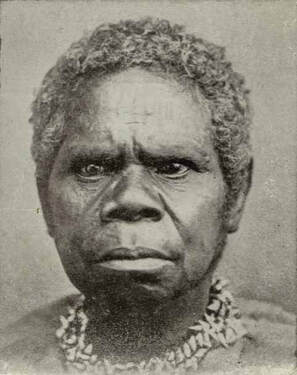

Truginini, photographed in 1866. Photo: Tasmanian Archives and Heritage Office

Truginini, photographed in 1866. Photo: Tasmanian Archives and Heritage Office By Ian Hayward Robinson

CASSANDRA Pybus's new book about Truginini, a Nuenonne woman from Bruny Island, off the south-east coast of Tasmania, is of special relevance to Bass Coast residents, as one of the most fateful episodes of her life occurred right here, near the mouth of the Powlett River, when she and her four indigenous companions were responsible for the deaths of two white whalers, an action for which the two males in her party were subsequently hanged.

Truganini survived and became famous in her later years as “the last Tasmanian Aborigine”. That she was the “last” was of course wishful thinking on the part of the Tasmanian white population. According to the ABS, there are currently about 20,000 people of Aboriginal descent living in Tasmania. Truginini’s celebrity presence in Hobart lasted until her death in 1876, and, as we shall see, for many years beyond.

CASSANDRA Pybus's new book about Truginini, a Nuenonne woman from Bruny Island, off the south-east coast of Tasmania, is of special relevance to Bass Coast residents, as one of the most fateful episodes of her life occurred right here, near the mouth of the Powlett River, when she and her four indigenous companions were responsible for the deaths of two white whalers, an action for which the two males in her party were subsequently hanged.

Truganini survived and became famous in her later years as “the last Tasmanian Aborigine”. That she was the “last” was of course wishful thinking on the part of the Tasmanian white population. According to the ABS, there are currently about 20,000 people of Aboriginal descent living in Tasmania. Truginini’s celebrity presence in Hobart lasted until her death in 1876, and, as we shall see, for many years beyond.

Truganini’s early history is not so well known. Born in about 1812, in her late teens Truganini was taken under the wing of the flawed do-gooder George Augustus Robinson (no relation) who saw his mission in life to save the native population of the newly settled colony from the genocidal settlers and to make good Christians out of them. Truginini and Robinson formed a relationship of sorts and she accompanied him on his extended journeys into the Tasmania wilderness during which he hoped to round up the surviving tribes-people and relocate them to Flinders Island. This was only partly successful, firstly because some of the Aboriginals managed to evade him, and secondly because Finders Island proved such a harsh inhospitable environment that many of the people he did manage to “save” died there prematurely. In 1847 the 46 survivors had to be moved back to the Tasmanian mainland to a (relatively) more hospitable site at Oyster Cove southeast of Hobart.

Truginini: Journey through

Truginini: Journey through the apocalypse

By Cassandra Pybus

Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 2020

In 1838 Robinson was appointed Chief Protector of Aborigines for the fledging Port Phillip District and he took Truganini and some of her companions with him to the new settlement in what would eventually become Victoria. Subsequent events have achieved some notoriety. Not long after they got there the Tasmanians were effectively abandoned by Robinson. Eventually Truganini joined up with two of the Tasmanian men, Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener, and two other women, Plorenernoopner and Maytepueminer. In 1841 they set out on a trek through the Bass Coast area of Gippsland, ostensibly to look for a third Tasmanian man, Lacklay, the husband of Maytepueminer, who had disappeared in the area.

The subsequent train of events is too complicated to summarise here, but the upshot was that Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener shot and killed two whalers who happened to be passing through the area, apparently in the mistaken belief that one of them was a settler called Watson, who, they also mistakenly believed, had killed Lacklay, the man they were looking for.

After a manhunt, the five Tasmanians were captured and were put on trial in Melbourne for murder. The three women were spared because Robinson convinced the jury that women in Tasmanian Aboriginal culture were totally under the control of the men and therefore had no agency in the murders. Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener were not permitted to testify in their own defence, on the grounds that they were not Christians, so could not give sworn evidence.

Despite a spirited plea by their court-appointed counsel, Redmond Barry, later famous for founding the University of Melbourne and being the judge in Ned Kelly’s trial, they were both convicted, and became the first people to be hanged in the new colony of Port Phillip. A plaque has recently been installed near where the hanging took place to commemorate their lives.

There has recently been some talk of erecting a monument to Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener in Bass Coast, celebrating them as “freedom fighters” who were “part of the widespread Aboriginal resistance to colonisation of the day”. However this seems to be reading too much into the sad events. Although they had all personally experienced enough betrayal and witnessed enough bastardry to justify an uprising, nothing they said or did supports this contention. As Pybus points out: “If they had intended to exact some kind of retribution for colonial dispossession it made no sense to travel all the way to a place almost bereft of settlers.” Moreover, if they were indeed “making war on the invaders”, as has been claimed, “[a]fter the shooting, the obvious course would have been to head westwards and make common cause with the aggrieved Kurnai in Gippsland, who had attacked the squatters the previous year. That is not what they did.” Instead they wandered around aimlessly for three weeks in the Western Port area, virtually waiting for the authorities to find them.

No, concludes Pybus, “[t]here was some other reason for their murderous action, a reason specific to that place.” The precise motivation for the shooting may never be known. Tunnerminnerwait remained resolutely silent after his capture. Maulboyheener blamed Tunnerminnerwait for forcing him to fire the fatal shot. Truganini’s only partial explanation was that they thought it was the settler Watson, who had fired on them previously.

These five Tasmanians had a long history of co-operating with the European invaders, which was why they were brought to the Port Phillip District by Robinson in the first place. This was not their country. As Tasmanians they were “strangers in a strange land” and thus unlikely to be part of any “anti-colonial resistance” as has been claimed. They were abysmally treated, initially by Robinson, and then by the colonial justice system. They were convicted by a foreign court under foreign laws and not allowed to speak in their own defence. The vengeful judge ignored the jury’s strong plea for mercy and was determined to have them hanged. It is for their shameful treatment by the white invaders that they should be remembered, not for any imaginary acts of resistance.

After the executions, Truganini and the other two women returned to Flinders Island and then Oyster Bay. Robinson had no further contact with her, despite the fact that she had twice saved his life in the Tasmanian wilderness. She spent her last years living with a settler family in Hobart and was a minor local celebrity. In 1868 she was presented to the visiting Duke of Edinburgh.

Before she died in 1876, she was concerned about her remains being exploited and exhibited, as had happened to other members of her people. To prevent this she was buried in a secret location. But two years later, her grave was raided, not by criminals but by the Royal Society of Tasmania! Her body was stolen and reduced to a skeleton, which was put on display in the Tasmanian Museum. It remained displayed there until 1947, an ironic monument to the way our ancestors treated the original (and arguably current) owners of this land as little better than animals: less than human whilst alive and museum exhibits once dead.

This is a book all Australians should read. They will not enjoy it. It is a painful experience. The author, Cassandra Pybus, takes us on a journey through the experience of the European invasion of Australia as experienced through the life story of this iconic Tasmanian Aboriginal woman. It is a tale of one betrayal after another. As the title warns us, the book evokes an apocalypse, and in both lower-case senses of the word. For every reader it involves reliving the ‘widespread destruction and disaster’ visited on indigenous lives and culture by Europeans. For the European reader, one hopes, it also leads to apocalypse as ‘revelation and discovery’, to a deeper understanding of what we have done.

In a moving Afterword Pybus places the tale of Truganini in the context of her own life and the current Aboriginal struggle for recognition and reconciliation. Without taking anything away from Truganini and her story, she brilliantly places it in both a personal and a national framework. She quotes the resonant words of Poor Fellow My Country author Xavier Herbert:

“Until we give back to the black man just a bit of land that was his and give it back without provisos, without strings to snatch it back, without anything but complete generosity of spirit in concession for the evil we have done him – until we do that, we shall remain what we have always been so far: a community of thieves.”

The Greek god Zeus gave Pybus’s namesake, the original Cassandra of ancient myth, the gift of always speaking the truth. But because she later rejected the god Apollo’s advances, while he couldn’t alter Zeus’s decree, Apollo cursed her so when she did speak the truth no one would believe her. Cassandra Pybus is speaking the truth in this important book. Forget fealty to Apollo. Pybus must be believed.

Ian Hayward Robinson has had a long interest in Truganini since he had a major role in the world (non-professional) premiere of Bill Reid’s play of the same name at Melbourne University in the early 70s. He is a member of the Bass Coast South Gippsland Reconciliation Group.

The subsequent train of events is too complicated to summarise here, but the upshot was that Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener shot and killed two whalers who happened to be passing through the area, apparently in the mistaken belief that one of them was a settler called Watson, who, they also mistakenly believed, had killed Lacklay, the man they were looking for.

After a manhunt, the five Tasmanians were captured and were put on trial in Melbourne for murder. The three women were spared because Robinson convinced the jury that women in Tasmanian Aboriginal culture were totally under the control of the men and therefore had no agency in the murders. Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener were not permitted to testify in their own defence, on the grounds that they were not Christians, so could not give sworn evidence.

Despite a spirited plea by their court-appointed counsel, Redmond Barry, later famous for founding the University of Melbourne and being the judge in Ned Kelly’s trial, they were both convicted, and became the first people to be hanged in the new colony of Port Phillip. A plaque has recently been installed near where the hanging took place to commemorate their lives.

There has recently been some talk of erecting a monument to Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener in Bass Coast, celebrating them as “freedom fighters” who were “part of the widespread Aboriginal resistance to colonisation of the day”. However this seems to be reading too much into the sad events. Although they had all personally experienced enough betrayal and witnessed enough bastardry to justify an uprising, nothing they said or did supports this contention. As Pybus points out: “If they had intended to exact some kind of retribution for colonial dispossession it made no sense to travel all the way to a place almost bereft of settlers.” Moreover, if they were indeed “making war on the invaders”, as has been claimed, “[a]fter the shooting, the obvious course would have been to head westwards and make common cause with the aggrieved Kurnai in Gippsland, who had attacked the squatters the previous year. That is not what they did.” Instead they wandered around aimlessly for three weeks in the Western Port area, virtually waiting for the authorities to find them.

No, concludes Pybus, “[t]here was some other reason for their murderous action, a reason specific to that place.” The precise motivation for the shooting may never be known. Tunnerminnerwait remained resolutely silent after his capture. Maulboyheener blamed Tunnerminnerwait for forcing him to fire the fatal shot. Truganini’s only partial explanation was that they thought it was the settler Watson, who had fired on them previously.

These five Tasmanians had a long history of co-operating with the European invaders, which was why they were brought to the Port Phillip District by Robinson in the first place. This was not their country. As Tasmanians they were “strangers in a strange land” and thus unlikely to be part of any “anti-colonial resistance” as has been claimed. They were abysmally treated, initially by Robinson, and then by the colonial justice system. They were convicted by a foreign court under foreign laws and not allowed to speak in their own defence. The vengeful judge ignored the jury’s strong plea for mercy and was determined to have them hanged. It is for their shameful treatment by the white invaders that they should be remembered, not for any imaginary acts of resistance.

After the executions, Truganini and the other two women returned to Flinders Island and then Oyster Bay. Robinson had no further contact with her, despite the fact that she had twice saved his life in the Tasmanian wilderness. She spent her last years living with a settler family in Hobart and was a minor local celebrity. In 1868 she was presented to the visiting Duke of Edinburgh.

Before she died in 1876, she was concerned about her remains being exploited and exhibited, as had happened to other members of her people. To prevent this she was buried in a secret location. But two years later, her grave was raided, not by criminals but by the Royal Society of Tasmania! Her body was stolen and reduced to a skeleton, which was put on display in the Tasmanian Museum. It remained displayed there until 1947, an ironic monument to the way our ancestors treated the original (and arguably current) owners of this land as little better than animals: less than human whilst alive and museum exhibits once dead.

This is a book all Australians should read. They will not enjoy it. It is a painful experience. The author, Cassandra Pybus, takes us on a journey through the experience of the European invasion of Australia as experienced through the life story of this iconic Tasmanian Aboriginal woman. It is a tale of one betrayal after another. As the title warns us, the book evokes an apocalypse, and in both lower-case senses of the word. For every reader it involves reliving the ‘widespread destruction and disaster’ visited on indigenous lives and culture by Europeans. For the European reader, one hopes, it also leads to apocalypse as ‘revelation and discovery’, to a deeper understanding of what we have done.

In a moving Afterword Pybus places the tale of Truganini in the context of her own life and the current Aboriginal struggle for recognition and reconciliation. Without taking anything away from Truganini and her story, she brilliantly places it in both a personal and a national framework. She quotes the resonant words of Poor Fellow My Country author Xavier Herbert:

“Until we give back to the black man just a bit of land that was his and give it back without provisos, without strings to snatch it back, without anything but complete generosity of spirit in concession for the evil we have done him – until we do that, we shall remain what we have always been so far: a community of thieves.”

The Greek god Zeus gave Pybus’s namesake, the original Cassandra of ancient myth, the gift of always speaking the truth. But because she later rejected the god Apollo’s advances, while he couldn’t alter Zeus’s decree, Apollo cursed her so when she did speak the truth no one would believe her. Cassandra Pybus is speaking the truth in this important book. Forget fealty to Apollo. Pybus must be believed.

Ian Hayward Robinson has had a long interest in Truganini since he had a major role in the world (non-professional) premiere of Bill Reid’s play of the same name at Melbourne University in the early 70s. He is a member of the Bass Coast South Gippsland Reconciliation Group.