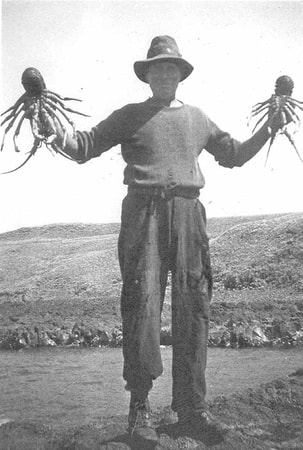

Norm’s grandfather Bill Jenner pictured on one of the back beaches in the late 1940s. There was full and plenty on Phillip Island if you knew where to look for it.

Norm’s grandfather Bill Jenner pictured on one of the back beaches in the late 1940s. There was full and plenty on Phillip Island if you knew where to look for it. By Norm Jenner

Following the great Depression of the early 1930s, there was little money around for luxuries such as bought food. On the Island, the farming community, especially, continued to live much as their ancestors had, on what they could grow themselves and on animals, birds and fish that they could capture. Among the favourite delicacies were the mutton bird (stormy petrel or shearwater) and their eggs.

The mutton birds breed in shallow burrows dug into the coastal dunes around the southern side of the island. Unlike the penguin, which is a permanent resident, the mutton bird migrates to warmer northern waters each autumn and returns with the mutton bird gales that usually start on November 4.

The mutton bird always returns to the same mate and the same burrow each year. There is hell to pay if something else is in there, such as a snake or rabbit. The birds look harmless enough but they have a savage hooked beak that can chop pieces out of your hand if you are not quick in retracting it. Last year’s chicks have to find an abandoned burrow to start their breeding life or scratch out a new one.

Following the great Depression of the early 1930s, there was little money around for luxuries such as bought food. On the Island, the farming community, especially, continued to live much as their ancestors had, on what they could grow themselves and on animals, birds and fish that they could capture. Among the favourite delicacies were the mutton bird (stormy petrel or shearwater) and their eggs.

The mutton birds breed in shallow burrows dug into the coastal dunes around the southern side of the island. Unlike the penguin, which is a permanent resident, the mutton bird migrates to warmer northern waters each autumn and returns with the mutton bird gales that usually start on November 4.

The mutton bird always returns to the same mate and the same burrow each year. There is hell to pay if something else is in there, such as a snake or rabbit. The birds look harmless enough but they have a savage hooked beak that can chop pieces out of your hand if you are not quick in retracting it. Last year’s chicks have to find an abandoned burrow to start their breeding life or scratch out a new one.

After scratching out the debris from the burrow, the female lays a single egg. It is this egg that we harvested, using a specially made wire loop about two metres long – called a mutton bird hook – to poke down the burrow and gently work out the egg. This can be tricky as the hen bird always tries to stop her egg being stolen and gets more savage as it is being moved out.

You have to wait until the egg is well out of the burrow before picking it up. Putting your hand down the burrow invites a savage peck from an irate bird or, worse, from the island’s only dangerous reptile – the copperhead snake, which also liked to frequent the burrows. The egg harvesting was carried out at dusk and dawn as it was illegal. The Fisheries and Game wardens were always on the lookout for perpetrators. In those times (the ’30s and ’40s) it was no trouble to bring home a big bucket of 10 or 12 dozen eggs.

The birds would lay a replacement egg, which we didn’t take. Instead we would pick up the loose eggs on top of the rookeries laid by hens caught short before they could get to a burrow.

You have to wait until the egg is well out of the burrow before picking it up. Putting your hand down the burrow invites a savage peck from an irate bird or, worse, from the island’s only dangerous reptile – the copperhead snake, which also liked to frequent the burrows. The egg harvesting was carried out at dusk and dawn as it was illegal. The Fisheries and Game wardens were always on the lookout for perpetrators. In those times (the ’30s and ’40s) it was no trouble to bring home a big bucket of 10 or 12 dozen eggs.

The birds would lay a replacement egg, which we didn’t take. Instead we would pick up the loose eggs on top of the rookeries laid by hens caught short before they could get to a burrow.

We would collect these latter eggs from around 2am on as the scavenger birds would arrive at daylight to eat any eggs that were lying about. “Picking up” required walking around the rookery in complete darkness and silence as any lights or noise could alert the inspectors.

Mutton bird eggs are an acquired taste. They make beautiful omelettes and are a gourmet’s delight hard boiled and eaten with vinegar, salt and pepper. Eggs surplus to immediate requirements were put down with “keepegg” for eating later in the year.

By the following March, the chicks are as big as their parents and the second harvest takes place. The same mutton bird hooks are used to gently coax the chick out of the burrow, where its neck is wrung. The birds are then taken down to the rocks on the seashore where the valuable oil sack that is part of their digestive system is removed together with their oil skins. The dressed birds would be taken home for roasting or to be smoked for later on.

The birds are also an acquired taste, but they were a part of our staple diet. At all times care had to be taken to dodge the authorities. Bill Gummisch (married to Dad’s sister Olive) would tell us how he would send his mate with no eggs or birds tearing up the road in his ute to be chased by the Fisheries and Game while Bill sneaked away quietly in the other direction with the booty. Bill said that he learnt all those tricks from his father Charlie, who was the Island’s policeman for many years.

Rabbits were an important part – both good and bad – of the Island economy. Mum liked to bake two young rabbits for our Sunday roast lunch with her special seasoning and gravy. Rabbits were a thriving pest, eating a lot of young green chicory and other crops. Most of the cropping paddocks were fenced with rabbit proof wire netting, but the rabbits would dig under the netting or squeeze through anywhere that the netting had been damaged. These rabbit runs, as they were called, were ideal spots for setting rabbit traps.

In the 1930s and 1940s, many otherwise jobless men made a living trapping rabbits. Their skins were dried and sold to merchants in Melbourne. The number of rabbits you could catch in a night was limited only by the number of traps that you could carry and set by yourself and also by the number of times you could go round them to remove the rabbits and reset the traps.

You had to do the first round at sunset to take out any magpies and other strays. You had to make at least one round after dark with the aid of a kerosene lantern and a chaff bag to carry the rabbits home in. Walking around in the dark by yourself could be a bit scary. Sometimes there would be a feral cat or a big hare to cope with. I never liked hares as they were too big and strong to do much with.

A bag of rabbits was no light weight to carry back home. My sister Lorraine liked to come around the traps with me. To make sure she would be ready for the early dawn round, she would go to bed fully dressed, including her footwear.

During the summer of 1947/48 Henry Jenner and I did quite well out of trapping rabbits. We made good money by just gutting the rabbits, hooking their back legs together into pairs and putting them over a broom handle strung across the handlebars of our bike. We could carry about 12 pairs each into Cowes to sell to the butcher for two shillings a large pair and one shilling a small pair. The two pounds or more earned was equal to a day’s wages hoeing chicory.

The other income came from selling rabbit skins. The skins were dried over V-shaped wire stretch frames and then packed in bundles and sent to a skin merchant in Melbourne to make men’s hats. The dried skins were quite light and it took a lot to make much money.

Another source of food supply and a favourite recreation was fishing off the ocean rocks along the southern part of the Island facing Bass Strait. Our fishing gear was rather crude – just a long thin tea-tree pole with a length of strong lightweight cord tied to it. We used a fairly heavy sinker to stop the line moving about too much in the rough water. The best fishing was from the most distant rocks that could only be reached at low tide. In most cases, there would be a big drop down to the water.

We caught parrot fish, leather-jackets, sweet lip and whiting. However, our favourite catch was crayfish or lobster. Dad was the resident crayfish-net maker. He would weave a round hooped net of just under a metre from fine cord. The net had two hoops, one about half a metre above the other, with the net across the bottom and round the sides. The top was open. We tied some ageing meat in the middle as bait, then tied three bridle ropes to the top hoop. They were attached to a single rope and the net was lowered into the water by means of a long forked stick holding out the single part of the rope. After about 20 minutes, the forked stick would be used in the same way to quickly reef the net upwards and out of the water. This fast upward motion would pull up the top hoop to trap whatever was inside – preferably at least one crayfish. Cooked crayfish tails are beautiful to eat, especially with salt pepper and vinegar.

As with fishing everywhere, there were favourite spots, the location of which was always jealously guarded. Dad always took several crayfish nets to cover all the likely spots. We always went fishing as a group: Dad, Uncle Allan, my cousin Henry, Pa and me.

Our grandfather, Pa Jenner, was a great fisherman. Fishing at the edge of rock outcrops has its dangers. “Never turn your back on the ocean,” Pa would tell us boys. “Watch for the turn of the tide.” And “Every seventh wave is a big one.”

All this advice was important as every so often a big wave would break right over the rock that we were fishing from and you had to be ready to hang on to everything, including your fishing gear. A succession of big waves meant the tide had turned and was now coming in and it was time to retreat to a safer position.

By the following March, the chicks are as big as their parents and the second harvest takes place. The same mutton bird hooks are used to gently coax the chick out of the burrow, where its neck is wrung. The birds are then taken down to the rocks on the seashore where the valuable oil sack that is part of their digestive system is removed together with their oil skins. The dressed birds would be taken home for roasting or to be smoked for later on.

The birds are also an acquired taste, but they were a part of our staple diet. At all times care had to be taken to dodge the authorities. Bill Gummisch (married to Dad’s sister Olive) would tell us how he would send his mate with no eggs or birds tearing up the road in his ute to be chased by the Fisheries and Game while Bill sneaked away quietly in the other direction with the booty. Bill said that he learnt all those tricks from his father Charlie, who was the Island’s policeman for many years.

Rabbits were an important part – both good and bad – of the Island economy. Mum liked to bake two young rabbits for our Sunday roast lunch with her special seasoning and gravy. Rabbits were a thriving pest, eating a lot of young green chicory and other crops. Most of the cropping paddocks were fenced with rabbit proof wire netting, but the rabbits would dig under the netting or squeeze through anywhere that the netting had been damaged. These rabbit runs, as they were called, were ideal spots for setting rabbit traps.

In the 1930s and 1940s, many otherwise jobless men made a living trapping rabbits. Their skins were dried and sold to merchants in Melbourne. The number of rabbits you could catch in a night was limited only by the number of traps that you could carry and set by yourself and also by the number of times you could go round them to remove the rabbits and reset the traps.

You had to do the first round at sunset to take out any magpies and other strays. You had to make at least one round after dark with the aid of a kerosene lantern and a chaff bag to carry the rabbits home in. Walking around in the dark by yourself could be a bit scary. Sometimes there would be a feral cat or a big hare to cope with. I never liked hares as they were too big and strong to do much with.

A bag of rabbits was no light weight to carry back home. My sister Lorraine liked to come around the traps with me. To make sure she would be ready for the early dawn round, she would go to bed fully dressed, including her footwear.

During the summer of 1947/48 Henry Jenner and I did quite well out of trapping rabbits. We made good money by just gutting the rabbits, hooking their back legs together into pairs and putting them over a broom handle strung across the handlebars of our bike. We could carry about 12 pairs each into Cowes to sell to the butcher for two shillings a large pair and one shilling a small pair. The two pounds or more earned was equal to a day’s wages hoeing chicory.

The other income came from selling rabbit skins. The skins were dried over V-shaped wire stretch frames and then packed in bundles and sent to a skin merchant in Melbourne to make men’s hats. The dried skins were quite light and it took a lot to make much money.

Another source of food supply and a favourite recreation was fishing off the ocean rocks along the southern part of the Island facing Bass Strait. Our fishing gear was rather crude – just a long thin tea-tree pole with a length of strong lightweight cord tied to it. We used a fairly heavy sinker to stop the line moving about too much in the rough water. The best fishing was from the most distant rocks that could only be reached at low tide. In most cases, there would be a big drop down to the water.

We caught parrot fish, leather-jackets, sweet lip and whiting. However, our favourite catch was crayfish or lobster. Dad was the resident crayfish-net maker. He would weave a round hooped net of just under a metre from fine cord. The net had two hoops, one about half a metre above the other, with the net across the bottom and round the sides. The top was open. We tied some ageing meat in the middle as bait, then tied three bridle ropes to the top hoop. They were attached to a single rope and the net was lowered into the water by means of a long forked stick holding out the single part of the rope. After about 20 minutes, the forked stick would be used in the same way to quickly reef the net upwards and out of the water. This fast upward motion would pull up the top hoop to trap whatever was inside – preferably at least one crayfish. Cooked crayfish tails are beautiful to eat, especially with salt pepper and vinegar.

As with fishing everywhere, there were favourite spots, the location of which was always jealously guarded. Dad always took several crayfish nets to cover all the likely spots. We always went fishing as a group: Dad, Uncle Allan, my cousin Henry, Pa and me.

Our grandfather, Pa Jenner, was a great fisherman. Fishing at the edge of rock outcrops has its dangers. “Never turn your back on the ocean,” Pa would tell us boys. “Watch for the turn of the tide.” And “Every seventh wave is a big one.”

All this advice was important as every so often a big wave would break right over the rock that we were fishing from and you had to be ready to hang on to everything, including your fishing gear. A succession of big waves meant the tide had turned and was now coming in and it was time to retreat to a safer position.

Born in 1934, Norm Jenner lived on Phillip Island with his family until 1948 when they shifted to Queensland in search of opportunities. This is an extract from a family history he wrote for his children and grandchildren. Norm died in 2015.