A memoir of life at Griffiths Point (San Remo) in the 1870s and 1880s makes fascinating and often harrowing reading.

By Samuel Jabez Pickersgill

I WAS born at Fiddler’s Green, so called by the old bay fishermen because they could always rely on getting fish they referred to as fiddlers in their nets when fishing there. So at Fiddler’s Green at San Remo, then known as Griffiths Point, I arrived on the scene on September 22nd, 1866. My parents, after six years at Churchill Island, having failed to acquire the right of occupying same, had lost their home to a Mr Rogers. My father was advised several times to select but he would not bother about it.

Mother had made a comfortable home on the little island. It is I think about 160 acres or so. Three of my sisters were born there: Louisa, Kate and Annie. Priscilla was born on French Island. The oldest sister Elizabeth was born in England and Robert William Pickersgill, the eldest of our family, was born in Melbourne.

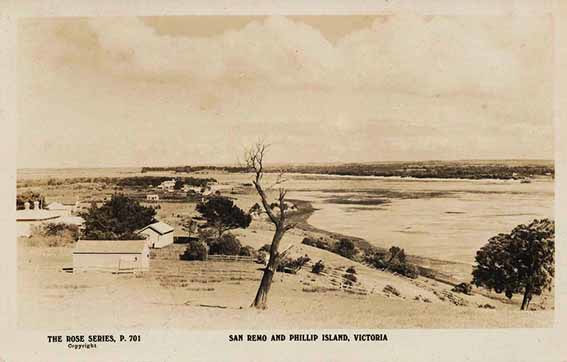

We lived only a few years at Fiddlers Green, then went on to the Bass where there was a small settlement at that time. My brother Walter was born there and shortly afterwards, the family settled down in a home on land father had selected, 163 acres fronting the ocean directly opposite Cape Woolamai. It was a lovely spot overlooking the bay and island on one side, and the ocean on the other. At that time Griffiths Point was very well timbered with sheoak trees and manna gums and black wattle. As the land was taken up and fenced, most of the occupiers (who were as a rule hard up) went in for log fences which was the start of the destruction of the timbered hills.

My first recollection of anything at Griffiths Point is our first arrival at the new home. I remember sitting up in the old cart behind the old bay horse Jock with a switch in hand to hurry him along.

Some year later, in 1878, my brother Robert William – known as Will – fell in love with Jennie McDonald of Stockyard Creek (now known as Foster). He first met her at Yanakie station, then owned by Willie Millar. Yanakie was originally taken up by McHaffie after he lost the lease of Phillip Island. Will met her while he was shearing for Millar who had taken over from McHaffie. She was a lovely little girl, fair with platinum hair. Her people were farmers. I remember that her brother Tom, a tall, weathered giant, brought her to Griffiths Point for the marriage. I was about 13 and Will was twenty five. Will and his bride lived at the old farm with us until his house was built. The old farm was in two blocks eighty odd acres each. Will was supposed to get one of them. There were at that time a number of unoccupied houses at Grantville, built of hardwood from an adjacent mill. Will bought one of them – a four roomed place complete with brick chimney, all for two pounds, pulled it to pieces, loaded it on a bullock wagon. He brought it to the farm block, all for another two pounds. No shortage of houses in those days. It was soon rebuilt. Father was very handy with tools and they were very comfortable in it for a year or so.

Jennie was expecting a baby and was having a very bad time in labour. Mother decided that it was beyond her and that she must have a doctor, as soon as possible. At that time the nearest doctor was at Cranbourne, forty miles away. No telephone or telegraph those days, or any means of communication at all. So Will must ride and ride fast. So off he went in frantic haste. At Bass he borrowed a fresh horse from Jack O’Meara, an old friend, and rode on through Lang Lang. At Caldermeade estate he got another fresh horse from McMillan the owner, a good one too, that carried him to Cranbourne. When he found the doctor and told him what he could about the trouble, Dr Eltham would not opt to have anything to do with a trip like that. Will was very much upset and pleaded with him. The doctor said “Well if you are prepared to give me fifty pounds before we start and find a buggy and a pair of hoses, I will think about it.”

Fifty pounds was a great lot of money in those times. Will said “I can’t give you the money now, but I shall see that you get it later on.” Doctor would not agree to that. After some little time he said “On second thoughts I do not care to go at all. I have patients here and can’t leave them. The best thing you can do it go to Hastings. There is a doctor there. Get him to go across the bay by boat.”

What with worrying about his wife and thinking of how she was suffering, Will must have been very upset and disappointed about the doctor’s refusal. So after a few minutes thought, he decided to go to Hastings. So he mounted his horse again and off he went. He knew a man and his wife is Hastings. A Mr and Mrs Barclay, both very old friends. So he went to them in his distress. They were both at home, but, before he could tell them what was the matter, he fainted for the first time in his life. He’d had nothing to eat since he left home. That and the worry was too much for him.

After they brought him around and gave him some stimulant and he had told them why he was there, they said “Doctor has been on the spree for the last week, he is not fit to see anyone. If he is fit at all I will take him and you over in my boat, but I’m afraid it is useless, but come along and we will see him.” So off they went. A housekeeper came to the door of the doctor’s house saying that he had not been out of bed for days: drunk and dead to the world. They had a talk to the housekeeper and told her all the facts. She was a woman and in sympathy with them. They all talked the matter over and came to the conclusion that the only thing to do was to bundle the doctor up and carry him to the boat. Mrs Barclay was I believe quite enthusiastic about it. And so they started across the bay with him.

It was unfortunately a very calm day so no wind at all. Barclay said “No good taking the big boat, we will have to take the skiff and row over”. Will said the doctor seemed quite unconscious of what was happening, as if he was in a state of torpor. They made him comfortable with rugs and cushions in the stern of the skiff and set out, Barclay and Will rowing and the Doctor lying on his back facing them. At times he would open his eyes and stir about a bit, but taking no notice of anything.

After a couple of hours or so he became violently sick and, after a while, appeared to be a bit brighter. It is I think about 25 miles from Hastings to San Remo, and, before the end of the long row, the doctor seemed to make a quick recovery and began to take stock of his surroundings. Will told us afterwards that he would never forget the look on his face and the flitting expressions passing over it. He said “My God, where in hell am I?? What are you men doing with me?? Are you going to drown me or what??”

Both Will and Barclay wore beards and must have looked rough and very determined men for anything. However, he at last recognised Barclay and was reassured when they explained matters to him. He behaved very well and did not blame them for what they had done. In fact he decided that they had probably acted in the best way for him, breaking him off his spree. I believe he was a good sort of chap, only for his fondness of whiskey.

In the meantime the baby had been born and everything was OK. The doctor went back next day per SS Eclipse and Will helped Barclay back with the skiff and returned the borrowed horses.

The baby had been born during the night after Will had left for the doctor. So in the morning I was told to saddle up my pony and ride along the main Melbourne road until I met them to give Will the good news. I was expected to meet him in a few hours. So off I went. I had never been further than the Bass township from Griffiths Point. After leaving Bass the road ran along the bayside at the foot of hills through scrubby country unfenced at the time. The track got too rough to follow and I had to make a new one through the scrub. When I got as far as Lang Lang, I began to think I had missed them on one of the bypasses through the scrub. However, I went on until I got to Tooradin. I had then travelled about thirty eight miles, so decided to turn back and head for home.

When we at last arrived home both the pony and I were tired and hungry. They had given me no lunch in my pocket and when I told them how far I had gone and seen nothing of Will and the Doctor, father said “I have a good mind to belt you from here to Tooradin”. I thought that rather tough after a ride of 75 miles. It must have been a good old pony though for she carried me along quite merrily, especially coming home.

Jennie and Will’s marriage was a love match, but as things turned out, very tough on them both. Up to Will’s wedding all he earned during that time went into the old home. When he married and settled on the block held by father, it was with expectation that it was to be his. Owing to some reason it did not turn out that way.

After a year or so he selected land up near Lang Lang, heavily timbered and only middling country. Somehow or other he built a house on it. He and Jennie and their family lived there for a few years under very hard and cruel conditions. They started absolutely from scratch. Not a penny behind them. Will working day and night. Mr Cox, the racing man of Moonee Valley, had taken up a lot of land in the neighbourhood. Will worked for him in the daytime and put in most of the night trying to clear his farm. It was hopeless from the start. Three other children were born there at great risk to Jennie’s life. During one of Will’s longer absences from home, the younger children were taken gravely ill.

Bob the eldest boy was at that time at his grandfather’s house at Griffiths Point. There were no near neighbours and no way of getting word to their father. The children seemed to be getting worse. Jennie was frantic, not knowing what was best to do with no Doctor anywhere near. She knew there was one at Griffiths Point, so she decided to pile rugs and blankets in the old trap they had, yoke up the horse, make the children as comfortable as she could and start out for the grandparents’ home at Griffiths Point and the Doctor 30 miles away. Poor girl, she had a dreadful time trying to attend to the poor sick kiddies and urge the slow old horse along.

Before she got there one of the children died. It was Diphtheria they had. Another died at the old home. Jennie herself, with the dreadful time she had gone through and the worry and pain of watching her child die, was almost dead too when she got there. She must have been rather a wonderful person to do what she did. Times were hard those days for anyone on the bread line, trying to get a start on the land, unless they had money to back them up.

They put in a few more years on the farm called Cherry Tree, trying hard to get a start. My brother after getting a lease of the land, borrowed money from the insurance companies on that security and, for the time, got some relief.

Jennie was going to have another baby. A nurse was engaged to attend her on the farm, but no doctor was available. The baby was born dead and in a few hours afterwards Jennie was dead also. Flooding had set in. No doctor being there, she had no hope.

Starting off as they did, sadly they had no real chance of success.

This essay was first broadcast on community radio station 3MFM with the assistance of a Local History grant from the Public Records Office of Victoria. It was edited and read by Christine Grayden, a descendant of the writer, and is published on the Phillip Island & District Historical Society website.

I WAS born at Fiddler’s Green, so called by the old bay fishermen because they could always rely on getting fish they referred to as fiddlers in their nets when fishing there. So at Fiddler’s Green at San Remo, then known as Griffiths Point, I arrived on the scene on September 22nd, 1866. My parents, after six years at Churchill Island, having failed to acquire the right of occupying same, had lost their home to a Mr Rogers. My father was advised several times to select but he would not bother about it.

Mother had made a comfortable home on the little island. It is I think about 160 acres or so. Three of my sisters were born there: Louisa, Kate and Annie. Priscilla was born on French Island. The oldest sister Elizabeth was born in England and Robert William Pickersgill, the eldest of our family, was born in Melbourne.

We lived only a few years at Fiddlers Green, then went on to the Bass where there was a small settlement at that time. My brother Walter was born there and shortly afterwards, the family settled down in a home on land father had selected, 163 acres fronting the ocean directly opposite Cape Woolamai. It was a lovely spot overlooking the bay and island on one side, and the ocean on the other. At that time Griffiths Point was very well timbered with sheoak trees and manna gums and black wattle. As the land was taken up and fenced, most of the occupiers (who were as a rule hard up) went in for log fences which was the start of the destruction of the timbered hills.

My first recollection of anything at Griffiths Point is our first arrival at the new home. I remember sitting up in the old cart behind the old bay horse Jock with a switch in hand to hurry him along.

Some year later, in 1878, my brother Robert William – known as Will – fell in love with Jennie McDonald of Stockyard Creek (now known as Foster). He first met her at Yanakie station, then owned by Willie Millar. Yanakie was originally taken up by McHaffie after he lost the lease of Phillip Island. Will met her while he was shearing for Millar who had taken over from McHaffie. She was a lovely little girl, fair with platinum hair. Her people were farmers. I remember that her brother Tom, a tall, weathered giant, brought her to Griffiths Point for the marriage. I was about 13 and Will was twenty five. Will and his bride lived at the old farm with us until his house was built. The old farm was in two blocks eighty odd acres each. Will was supposed to get one of them. There were at that time a number of unoccupied houses at Grantville, built of hardwood from an adjacent mill. Will bought one of them – a four roomed place complete with brick chimney, all for two pounds, pulled it to pieces, loaded it on a bullock wagon. He brought it to the farm block, all for another two pounds. No shortage of houses in those days. It was soon rebuilt. Father was very handy with tools and they were very comfortable in it for a year or so.

Jennie was expecting a baby and was having a very bad time in labour. Mother decided that it was beyond her and that she must have a doctor, as soon as possible. At that time the nearest doctor was at Cranbourne, forty miles away. No telephone or telegraph those days, or any means of communication at all. So Will must ride and ride fast. So off he went in frantic haste. At Bass he borrowed a fresh horse from Jack O’Meara, an old friend, and rode on through Lang Lang. At Caldermeade estate he got another fresh horse from McMillan the owner, a good one too, that carried him to Cranbourne. When he found the doctor and told him what he could about the trouble, Dr Eltham would not opt to have anything to do with a trip like that. Will was very much upset and pleaded with him. The doctor said “Well if you are prepared to give me fifty pounds before we start and find a buggy and a pair of hoses, I will think about it.”

Fifty pounds was a great lot of money in those times. Will said “I can’t give you the money now, but I shall see that you get it later on.” Doctor would not agree to that. After some little time he said “On second thoughts I do not care to go at all. I have patients here and can’t leave them. The best thing you can do it go to Hastings. There is a doctor there. Get him to go across the bay by boat.”

What with worrying about his wife and thinking of how she was suffering, Will must have been very upset and disappointed about the doctor’s refusal. So after a few minutes thought, he decided to go to Hastings. So he mounted his horse again and off he went. He knew a man and his wife is Hastings. A Mr and Mrs Barclay, both very old friends. So he went to them in his distress. They were both at home, but, before he could tell them what was the matter, he fainted for the first time in his life. He’d had nothing to eat since he left home. That and the worry was too much for him.

After they brought him around and gave him some stimulant and he had told them why he was there, they said “Doctor has been on the spree for the last week, he is not fit to see anyone. If he is fit at all I will take him and you over in my boat, but I’m afraid it is useless, but come along and we will see him.” So off they went. A housekeeper came to the door of the doctor’s house saying that he had not been out of bed for days: drunk and dead to the world. They had a talk to the housekeeper and told her all the facts. She was a woman and in sympathy with them. They all talked the matter over and came to the conclusion that the only thing to do was to bundle the doctor up and carry him to the boat. Mrs Barclay was I believe quite enthusiastic about it. And so they started across the bay with him.

It was unfortunately a very calm day so no wind at all. Barclay said “No good taking the big boat, we will have to take the skiff and row over”. Will said the doctor seemed quite unconscious of what was happening, as if he was in a state of torpor. They made him comfortable with rugs and cushions in the stern of the skiff and set out, Barclay and Will rowing and the Doctor lying on his back facing them. At times he would open his eyes and stir about a bit, but taking no notice of anything.

After a couple of hours or so he became violently sick and, after a while, appeared to be a bit brighter. It is I think about 25 miles from Hastings to San Remo, and, before the end of the long row, the doctor seemed to make a quick recovery and began to take stock of his surroundings. Will told us afterwards that he would never forget the look on his face and the flitting expressions passing over it. He said “My God, where in hell am I?? What are you men doing with me?? Are you going to drown me or what??”

Both Will and Barclay wore beards and must have looked rough and very determined men for anything. However, he at last recognised Barclay and was reassured when they explained matters to him. He behaved very well and did not blame them for what they had done. In fact he decided that they had probably acted in the best way for him, breaking him off his spree. I believe he was a good sort of chap, only for his fondness of whiskey.

In the meantime the baby had been born and everything was OK. The doctor went back next day per SS Eclipse and Will helped Barclay back with the skiff and returned the borrowed horses.

The baby had been born during the night after Will had left for the doctor. So in the morning I was told to saddle up my pony and ride along the main Melbourne road until I met them to give Will the good news. I was expected to meet him in a few hours. So off I went. I had never been further than the Bass township from Griffiths Point. After leaving Bass the road ran along the bayside at the foot of hills through scrubby country unfenced at the time. The track got too rough to follow and I had to make a new one through the scrub. When I got as far as Lang Lang, I began to think I had missed them on one of the bypasses through the scrub. However, I went on until I got to Tooradin. I had then travelled about thirty eight miles, so decided to turn back and head for home.

When we at last arrived home both the pony and I were tired and hungry. They had given me no lunch in my pocket and when I told them how far I had gone and seen nothing of Will and the Doctor, father said “I have a good mind to belt you from here to Tooradin”. I thought that rather tough after a ride of 75 miles. It must have been a good old pony though for she carried me along quite merrily, especially coming home.

Jennie and Will’s marriage was a love match, but as things turned out, very tough on them both. Up to Will’s wedding all he earned during that time went into the old home. When he married and settled on the block held by father, it was with expectation that it was to be his. Owing to some reason it did not turn out that way.

After a year or so he selected land up near Lang Lang, heavily timbered and only middling country. Somehow or other he built a house on it. He and Jennie and their family lived there for a few years under very hard and cruel conditions. They started absolutely from scratch. Not a penny behind them. Will working day and night. Mr Cox, the racing man of Moonee Valley, had taken up a lot of land in the neighbourhood. Will worked for him in the daytime and put in most of the night trying to clear his farm. It was hopeless from the start. Three other children were born there at great risk to Jennie’s life. During one of Will’s longer absences from home, the younger children were taken gravely ill.

Bob the eldest boy was at that time at his grandfather’s house at Griffiths Point. There were no near neighbours and no way of getting word to their father. The children seemed to be getting worse. Jennie was frantic, not knowing what was best to do with no Doctor anywhere near. She knew there was one at Griffiths Point, so she decided to pile rugs and blankets in the old trap they had, yoke up the horse, make the children as comfortable as she could and start out for the grandparents’ home at Griffiths Point and the Doctor 30 miles away. Poor girl, she had a dreadful time trying to attend to the poor sick kiddies and urge the slow old horse along.

Before she got there one of the children died. It was Diphtheria they had. Another died at the old home. Jennie herself, with the dreadful time she had gone through and the worry and pain of watching her child die, was almost dead too when she got there. She must have been rather a wonderful person to do what she did. Times were hard those days for anyone on the bread line, trying to get a start on the land, unless they had money to back them up.

They put in a few more years on the farm called Cherry Tree, trying hard to get a start. My brother after getting a lease of the land, borrowed money from the insurance companies on that security and, for the time, got some relief.

Jennie was going to have another baby. A nurse was engaged to attend her on the farm, but no doctor was available. The baby was born dead and in a few hours afterwards Jennie was dead also. Flooding had set in. No doctor being there, she had no hope.

Starting off as they did, sadly they had no real chance of success.

This essay was first broadcast on community radio station 3MFM with the assistance of a Local History grant from the Public Records Office of Victoria. It was edited and read by Christine Grayden, a descendant of the writer, and is published on the Phillip Island & District Historical Society website.