By Mrs I K Ledwidge

As Miss Somerset, I was appointed by the Victorian Education Department to the Powlett Coal Field School in 1910. The school was situated opposite the State Mine Office, one of the few buildings that wasn’t a tent in a town of tents that had sprung up, almost miraculously, when the first shaft was lowered for the State Coal Mine in November 1909.

As Miss Somerset, I was appointed by the Victorian Education Department to the Powlett Coal Field School in 1910. The school was situated opposite the State Mine Office, one of the few buildings that wasn’t a tent in a town of tents that had sprung up, almost miraculously, when the first shaft was lowered for the State Coal Mine in November 1909.

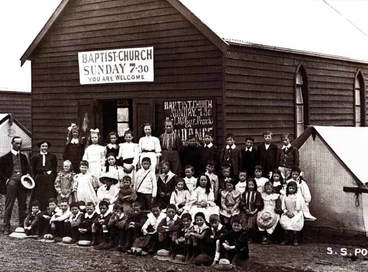

I was to teach under Mr Abercombie, Head Teacher, who opened the school in February 1910. By the time I was appointed, the Baptist Church had been moved by bullocks and dray from Morwell to Tent Town on the coal field. We two teachers shared the small one-room weatherboard church building to teach in. Later, a tent was erected at the back of the church for the lower grades. This contained a pine floor, boarded sides, but a tent roof and fly. It was very comfortable and novel to me, but was not to the children who all came from tent homes.

Mr Gardner was next to be appointed junior teacher. He shared the church with Mr Abercrombie for some time, while I taught the littlies in the tent.

A pupil of those days, Bessie Crawford, has a picture of this building with children then attending the school posing for the photographer out front. Although there was a big “Baptist Church” sign over the door and no signage at all indicating it was also a school, our school was known as the “Powlett School”. There was also a Powlett River School over at Heslop’s property two or three miles away, which was in existence many years before we started. No one confused us with them.

I rode my pony, Pepper, to school from Hicksborough every morning. The boys looked after my pony and I had plenty of grooms.

We were visited that first year by the Education Department Inspector, Mr Tate, who culled two marks from our Head Teacher’s report for a muddy assembly yard. How could it be anything but muddy when it was the street and surrounding area over which wagons passed daily with timber and mine supplies? My percentage from Mr Tate was 88 per cent. I never asked why the 12 per cent was deducted from my score. I was young and too afraid of the Inspector.

During 1910, surveyors were at work pegging out the township and shopping sites. Street construction was advancing with shops, houses and churches being built down the new street. It was not unusual for the surrounding country folk from far and wide to turn up to Wonthaggi – as the area was now known – each weekend to see the progress being made.

Our school, church and tent, was shifted and re-erected on the Church of England Hill; perhaps on the spot where the Church of England Sunday School now stands. Here we carried on with a growing attendance weekly until those two little buildings became inadequate.

Our next move was to the Methodist Church, which was a galvanized-iron building. We were all under one roof then. It was here that my colleague, Mr Lawson, took charge as senior assistant with two more junior teachers and we carried on in spite of attendance continuing to mushroom every week.

The Methodist church did not remain an iron building for very long. During part of our tenancy there, the carpenters built a wooden building over our heads, larger and more comfortable.

Meanwhile, the building of a brick school that was to become the Wonthaggi Primary School on Billson Street was begun and was growing apace. Senior classes were transferred to the new building as soon as rooms were sufficiently advanced to be serviceable. I never saw much of our head teacher after this. Gradually only from 2nd class down was left at the Methodist Church School and so we were moved into a hall at the back of the church near where the Union Theatre now stands. We had to squeeze through a narrow lane between two shops fronting Graham Street to get to the hall. It wasn’t very satisfactory.

Our last move was to the Wonthaggi Town Hall with one class being taught on the top of Pease’s building, which is now the Aywon Factory. As seating accommodation was not equal to the demand, the senior boys at the brick school borrowed planks from the builders and kerosene cases from the grocer’s to erect benches. On these sat many of my very young charges, who often dozed off to sleep.

A memorable day came with the visit of another Education Department Inspector named Mr Betheras. He was very different from Mr Tate. He laughed when he arrived and told Miss Lawson we were mad to try to teach under such conditions. He gave us full marks on sight.

Our staff by this time was considerable. Before we moved into the brick school, several seniors were enrolled as student teachers and many were helpers at morning tea or afternoon periods. One of these was Miss Humphries, now Mrs F. Quinn.

The last class occupying the Town Hall was the second class, compromising approximately one hundred pupils. Mr Jack Findlayson and I were in charge. When these children were accommodated at last in the brick building, I joined the relieving staff of the Victorian Education Department and served in many one-teacher country schools until I got married and became Mrs I. K. Ledwidge.

This essay was first published in The Plod, the newsletter of the Wonthaggi Historical Society, from a manuscript held in the Wonthaggi Museum.

Mr Gardner was next to be appointed junior teacher. He shared the church with Mr Abercrombie for some time, while I taught the littlies in the tent.

A pupil of those days, Bessie Crawford, has a picture of this building with children then attending the school posing for the photographer out front. Although there was a big “Baptist Church” sign over the door and no signage at all indicating it was also a school, our school was known as the “Powlett School”. There was also a Powlett River School over at Heslop’s property two or three miles away, which was in existence many years before we started. No one confused us with them.

I rode my pony, Pepper, to school from Hicksborough every morning. The boys looked after my pony and I had plenty of grooms.

We were visited that first year by the Education Department Inspector, Mr Tate, who culled two marks from our Head Teacher’s report for a muddy assembly yard. How could it be anything but muddy when it was the street and surrounding area over which wagons passed daily with timber and mine supplies? My percentage from Mr Tate was 88 per cent. I never asked why the 12 per cent was deducted from my score. I was young and too afraid of the Inspector.

During 1910, surveyors were at work pegging out the township and shopping sites. Street construction was advancing with shops, houses and churches being built down the new street. It was not unusual for the surrounding country folk from far and wide to turn up to Wonthaggi – as the area was now known – each weekend to see the progress being made.

Our school, church and tent, was shifted and re-erected on the Church of England Hill; perhaps on the spot where the Church of England Sunday School now stands. Here we carried on with a growing attendance weekly until those two little buildings became inadequate.

Our next move was to the Methodist Church, which was a galvanized-iron building. We were all under one roof then. It was here that my colleague, Mr Lawson, took charge as senior assistant with two more junior teachers and we carried on in spite of attendance continuing to mushroom every week.

The Methodist church did not remain an iron building for very long. During part of our tenancy there, the carpenters built a wooden building over our heads, larger and more comfortable.

Meanwhile, the building of a brick school that was to become the Wonthaggi Primary School on Billson Street was begun and was growing apace. Senior classes were transferred to the new building as soon as rooms were sufficiently advanced to be serviceable. I never saw much of our head teacher after this. Gradually only from 2nd class down was left at the Methodist Church School and so we were moved into a hall at the back of the church near where the Union Theatre now stands. We had to squeeze through a narrow lane between two shops fronting Graham Street to get to the hall. It wasn’t very satisfactory.

Our last move was to the Wonthaggi Town Hall with one class being taught on the top of Pease’s building, which is now the Aywon Factory. As seating accommodation was not equal to the demand, the senior boys at the brick school borrowed planks from the builders and kerosene cases from the grocer’s to erect benches. On these sat many of my very young charges, who often dozed off to sleep.

A memorable day came with the visit of another Education Department Inspector named Mr Betheras. He was very different from Mr Tate. He laughed when he arrived and told Miss Lawson we were mad to try to teach under such conditions. He gave us full marks on sight.

Our staff by this time was considerable. Before we moved into the brick school, several seniors were enrolled as student teachers and many were helpers at morning tea or afternoon periods. One of these was Miss Humphries, now Mrs F. Quinn.

The last class occupying the Town Hall was the second class, compromising approximately one hundred pupils. Mr Jack Findlayson and I were in charge. When these children were accommodated at last in the brick building, I joined the relieving staff of the Victorian Education Department and served in many one-teacher country schools until I got married and became Mrs I. K. Ledwidge.

This essay was first published in The Plod, the newsletter of the Wonthaggi Historical Society, from a manuscript held in the Wonthaggi Museum.