By Carolyn Landon

WHEN we moved from our farm in the Strzelecki hills to Wonthaggi in 2005 our focus was mainly on the beaches. We would wander from the Channel at Cape Paterson past First and Second Surf beaches towards Harmers Haven, past Wreck Beach where the “biggest whale ever” had been beached and where the rusted ribs left over from the Artisan wreckage lay. It took a bit of time and familiarity for us to discover the path to Williamsons Beach through the scrub followed by the walk to Powlett River, our eyes on the waves and surfers rather than the dunes and nesting birds. Later, with some guidance, we found the path through the bush to Cutlers Beach at the end of Chisholm Road and recognised the middens there spread out over millennia by the Bunurong.

WHEN we moved from our farm in the Strzelecki hills to Wonthaggi in 2005 our focus was mainly on the beaches. We would wander from the Channel at Cape Paterson past First and Second Surf beaches towards Harmers Haven, past Wreck Beach where the “biggest whale ever” had been beached and where the rusted ribs left over from the Artisan wreckage lay. It took a bit of time and familiarity for us to discover the path to Williamsons Beach through the scrub followed by the walk to Powlett River, our eyes on the waves and surfers rather than the dunes and nesting birds. Later, with some guidance, we found the path through the bush to Cutlers Beach at the end of Chisholm Road and recognised the middens there spread out over millennia by the Bunurong.

It took a long time for us to turn our focus inland and enter the State Coal Mine at Eastern Area for a tour underground. The experience was truly unforgettable: a bit frightening, a bit awe inspiring. The experience convinced us to explore the area out past the hospital on West Area Road where the deteriorating No.5 Brace stands. We had been familiar with No.5 Brace long before we actually went to look at it since its image was ever-present at local art exhibitions or in photographs in store windows, or on display in the Historical Society. Artists seemed fascinated by its tragic grandeur as it slowly deteriorated over the years after coal ran out in the area it served and it stopped operating after 57 years of constant operation. Even before we actually experienced being underground or had any clear sense of what it took to be a coal miner, or how extracting coal from underground actually worked, or even what a brace was, we understood that those images of No.5 Brace were iconic and powerful.

The structure had been the largest and most productive of all the braces around Wonthaggi and seemed to represent all that Wonthaggi stood for: the pride in the extraordinary work that went on here starting in 1909, the camaraderie of workers from many nations, the belief in the power of the Miners Union to protect the workers and their families, the cherishing of community and equality, the right of every citizen to have a voice and the need for all to care for one another.

That No.5 Brace was deteriorating and would soon be gone altogether seemed to be locking away that proud past. And people clearly felt it was a tragedy. When we finally cycled along West Area Road to look at the structure, the gate was closed, and we merely looked from the road. The area was very much overgrown and uninviting for novice walkers, and so we rode on.

In 2009, the overgrown bush near 5 Brace had made it almost impossible to find the first shafts 1, 2, 3 and 4 sunk for the new mine 100 years earlier, until some dedicated people from the Historical Society mounted a concerted effort. It was John Bordignon and Dennis Leversha who pushed their way through the scrub and confirmed that they had at last found the first shafts that began the extraordinary endeavour that would become the Wonthaggi Coal Mine. Dennis’s son Ben used his machinery to carve a path past the overgrown stone slagheap, through “clumps” of tea-tree which had been there since time immemorial and masses of weedy foreign bushes blown in over time.

These shafts were pretty much in the shadow of No.5 Brace, and it was there that the Historical Society held a celebration to mark the opening of the walk to the “Pioneer Mines” that included a performance from the Wonthaggi Citizens’ Band, a loud singing of “Part of my Heart”, a dramatic performance written by Gill Heal and acted by well-known local performers in front of a large crowd as it pushed past the shafts. All of this was followed by a picnic lunch held in the shadow of a tragically crumbling No.5 Brace looming in the background.

This celebration should have been a new beginning for a remembered past, but soon Parks Victoria realised that exposed shafts posed a danger to walkers and so they “capped” the shafts, filling them with stone partly to find out if they would sink, which one of them seems to be doing. Although, Parks has kept the path somewhat cleared and overlaid with gravel, the historical signs supplied by the Historical Society explaining the area have disappeared.

Nevertheless, Parks began to realise that many people loved to walk around the area dominated by No.5 Brace, and so they cleared a parking area, and have kept the cleared paddock around the Brace and near the Rescue Station mowed. They have minimally cleared the trails that had evolved from the footsteps of walkers, the tyres of bicycles and motorbikes, and now they regularly spray the thistles and flowering weeds and mow along the paths at intervals. A new map was been drawn up in detail by Dennis Leversha which includes most of the area served by 5 Brace – the Pioneer Mines (Shafts 1, 2, 3 and 4), Central Area (Shafts 9 and 10), Western Area (shafts 21 and 22) and the three McBride Tunnel benches, which all together had been the most productive area in the Wonthaggi Coal mines’ history.

The first time we walked there was with friends – not all of them old timers or any more au fait with Wonthaggi’s mining history than we were – we headed from the car park across the field towards No. 5 Brace taking note of its dilapidation, then veered off to the left to climb up some steep steps shoved into the side of a hill with stones and logs. The hill was long and narrow and the top of it was easy walking since it was absolutely level and layered with red stone. This part of the walk was labelled “Endless Haulage” on Dennis’s map, but we realised we were walking on the 3-kilometre-long shunt that had once carried skips pulled by an “Endless Haulage Line” from Western Area mines to No.5 Brace where they were emptied and sent back to be re-filled. It wasn’t the only Endless Haulage Line: there was another one pulling skips to and from McBride Tunnel and yet another one from 9 & 10 shafts, which were up near the bird hide Nola Thorpe and Terri Allen had first shown us.

Of course, on that first walk we didn’t know how the shunt was created or what it was for or where the shafts it served were; we didn’t know how it came to be there or who built it or how it was connected to the Brace; we had no idea what “endless haulage” meant; we didn’t know about the two other older haulage lines; we didn’t recognise that the huge hill covered in bush we had to walk around on our way back to the car park was actually a slag heap or stone dump that had once been three times bigger than it is now and had always for years been on fire as all the slag heaps around the different braces in Wonthaggi were since it was impossible to remove all the coal dust off the stone that came out of the mines with the coal and so as the stone waste settled the coal dust would heat up and burn turning the stone red.

The structure had been the largest and most productive of all the braces around Wonthaggi and seemed to represent all that Wonthaggi stood for: the pride in the extraordinary work that went on here starting in 1909, the camaraderie of workers from many nations, the belief in the power of the Miners Union to protect the workers and their families, the cherishing of community and equality, the right of every citizen to have a voice and the need for all to care for one another.

That No.5 Brace was deteriorating and would soon be gone altogether seemed to be locking away that proud past. And people clearly felt it was a tragedy. When we finally cycled along West Area Road to look at the structure, the gate was closed, and we merely looked from the road. The area was very much overgrown and uninviting for novice walkers, and so we rode on.

In 2009, the overgrown bush near 5 Brace had made it almost impossible to find the first shafts 1, 2, 3 and 4 sunk for the new mine 100 years earlier, until some dedicated people from the Historical Society mounted a concerted effort. It was John Bordignon and Dennis Leversha who pushed their way through the scrub and confirmed that they had at last found the first shafts that began the extraordinary endeavour that would become the Wonthaggi Coal Mine. Dennis’s son Ben used his machinery to carve a path past the overgrown stone slagheap, through “clumps” of tea-tree which had been there since time immemorial and masses of weedy foreign bushes blown in over time.

These shafts were pretty much in the shadow of No.5 Brace, and it was there that the Historical Society held a celebration to mark the opening of the walk to the “Pioneer Mines” that included a performance from the Wonthaggi Citizens’ Band, a loud singing of “Part of my Heart”, a dramatic performance written by Gill Heal and acted by well-known local performers in front of a large crowd as it pushed past the shafts. All of this was followed by a picnic lunch held in the shadow of a tragically crumbling No.5 Brace looming in the background.

This celebration should have been a new beginning for a remembered past, but soon Parks Victoria realised that exposed shafts posed a danger to walkers and so they “capped” the shafts, filling them with stone partly to find out if they would sink, which one of them seems to be doing. Although, Parks has kept the path somewhat cleared and overlaid with gravel, the historical signs supplied by the Historical Society explaining the area have disappeared.

Nevertheless, Parks began to realise that many people loved to walk around the area dominated by No.5 Brace, and so they cleared a parking area, and have kept the cleared paddock around the Brace and near the Rescue Station mowed. They have minimally cleared the trails that had evolved from the footsteps of walkers, the tyres of bicycles and motorbikes, and now they regularly spray the thistles and flowering weeds and mow along the paths at intervals. A new map was been drawn up in detail by Dennis Leversha which includes most of the area served by 5 Brace – the Pioneer Mines (Shafts 1, 2, 3 and 4), Central Area (Shafts 9 and 10), Western Area (shafts 21 and 22) and the three McBride Tunnel benches, which all together had been the most productive area in the Wonthaggi Coal mines’ history.

The first time we walked there was with friends – not all of them old timers or any more au fait with Wonthaggi’s mining history than we were – we headed from the car park across the field towards No. 5 Brace taking note of its dilapidation, then veered off to the left to climb up some steep steps shoved into the side of a hill with stones and logs. The hill was long and narrow and the top of it was easy walking since it was absolutely level and layered with red stone. This part of the walk was labelled “Endless Haulage” on Dennis’s map, but we realised we were walking on the 3-kilometre-long shunt that had once carried skips pulled by an “Endless Haulage Line” from Western Area mines to No.5 Brace where they were emptied and sent back to be re-filled. It wasn’t the only Endless Haulage Line: there was another one pulling skips to and from McBride Tunnel and yet another one from 9 & 10 shafts, which were up near the bird hide Nola Thorpe and Terri Allen had first shown us.

Of course, on that first walk we didn’t know how the shunt was created or what it was for or where the shafts it served were; we didn’t know how it came to be there or who built it or how it was connected to the Brace; we had no idea what “endless haulage” meant; we didn’t know about the two other older haulage lines; we didn’t recognise that the huge hill covered in bush we had to walk around on our way back to the car park was actually a slag heap or stone dump that had once been three times bigger than it is now and had always for years been on fire as all the slag heaps around the different braces in Wonthaggi were since it was impossible to remove all the coal dust off the stone that came out of the mines with the coal and so as the stone waste settled the coal dust would heat up and burn turning the stone red.

| We had a lot to learn but in the meantime we walked along the shunt marvelling at the stunning views way below us of the landscape between the shunt and the Rail Trail until we found the paths that meandered off the other side of the shunt and walked down into beautiful gullies filled with natural bush that hadn’t been touched since the main activity at the mine ceased in Central Area and left the No.5 Brace area dormant. We marvelled at the thick trunks of the forest of messmates with their over-reaching branches, and the thick ferns and many flourishing grasstrees that Terri says were the only species actually planted there by the Conservation Society. All the rest was natural and stunningly beautiful. There was something magical there, and we returned regularly through the seasons as plants flowered and grew and trees blossomed or dropped leaves and wildlife flourished. By the time we started walking regularly at No.5 Brace, I had learned a fair bit – especially from Lyn Chambers – about the politics of Wonthaggi, about the Union, the organisation of workers in bords, the actual working conditions in the mine, the Miners’ Women’s Auxiliary, the Co-op, the hospital, but I had no idea how the mine actually worked, how, once the coal was hewed down in the dark mines and picked up in the skips drawn by the ponies with their wheelers, then clipped to haulage lines and where the coal went after that. |

So I went to the Historical Society archive, grabbed a handful of books, photographs and general information and went to see John Bordignon.

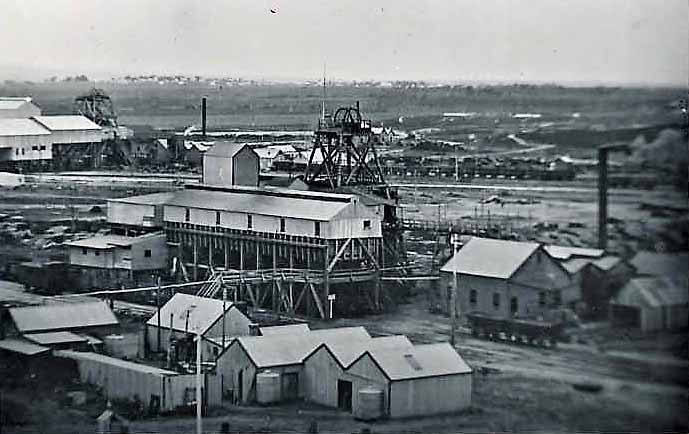

The first thing John showed me was a photograph of the land before any mine had ever been there, when it was basically a low-lying open and sometimes swampy paddock running from Anderson along the Powlett past Wonthaggi that had for years been grazed by cattle. There were no gullies and no valleys, no trainline, no mountainous slagheaps, no shafts, no shunts, no braces or powerhouse or brickworks. But from 1909, it all began to change at a rate of knots.

John Bordignon claims he did not write the information that comes next from an anonymous piece found in the archives at the Historical Society, but he says it is accurate:

No.5 Brace was built in early 1910. It was intended to become the main screening plant for several mines in the area. The mine manager, Mr Broome, a man at the top of his game and highly respected, oversaw the creation of a very large and modern brace, incorporating large coal bunkers and modern coal tipplers to accommodate all the coal coming – at first – from six connected shafts in Central Area all at once. All the coal was wound through 6, 7, 8 and 11 shafts through to 3 and 5 shafts. In the beginning, all the coal in skips that came into No.5 Brace came to the surface at the third floor of the brace in cages from a shaft 46 metres deep. The skips were then weighed and gravitated to a three-compartment tippler which relied on the weight of the skip to rotate one-third of a rotation at a time and by the time the tippler had made a full rotation the skip would be empty and would be knocked out of the way by the next full skip and gravitate back to the shaft.

The first thing John showed me was a photograph of the land before any mine had ever been there, when it was basically a low-lying open and sometimes swampy paddock running from Anderson along the Powlett past Wonthaggi that had for years been grazed by cattle. There were no gullies and no valleys, no trainline, no mountainous slagheaps, no shafts, no shunts, no braces or powerhouse or brickworks. But from 1909, it all began to change at a rate of knots.

John Bordignon claims he did not write the information that comes next from an anonymous piece found in the archives at the Historical Society, but he says it is accurate:

No.5 Brace was built in early 1910. It was intended to become the main screening plant for several mines in the area. The mine manager, Mr Broome, a man at the top of his game and highly respected, oversaw the creation of a very large and modern brace, incorporating large coal bunkers and modern coal tipplers to accommodate all the coal coming – at first – from six connected shafts in Central Area all at once. All the coal was wound through 6, 7, 8 and 11 shafts through to 3 and 5 shafts. In the beginning, all the coal in skips that came into No.5 Brace came to the surface at the third floor of the brace in cages from a shaft 46 metres deep. The skips were then weighed and gravitated to a three-compartment tippler which relied on the weight of the skip to rotate one-third of a rotation at a time and by the time the tippler had made a full rotation the skip would be empty and would be knocked out of the way by the next full skip and gravitate back to the shaft.

The coal would fall onto shaking screens on the second floor with different sized meshes which graded the contents of the skip to “slack” or “fine powdery coal” or “nutty coal” 25-50mm round. Only the nutty coal wash was transported to hopper bins via conveyor belt. The large coal ran onto picking tables where the brace boys [14 years old in their first jobs at the mine] or older men would pick out any splint or rock from the coal prior to the coal falling into rail trucks that ran under the brace and from there to be carted away.

In 1911, one year later, 9 and10 shafts opened up a fair distance from the Brace near the bird hide and an endless haulage line two kilometres long was established to take the coal past the Powerhouse where the electricity for the mine was being produced – one of the first all-electric braces in the world – around a bend and into No.5 Brace, entering the building via a long ramp to the top storey on the south- east corner. Then when McBride Tunnel area opened up, in 1915, skips entered the Brace from a ramp on the north-east corner via another endless haulage system.

In 1927, after producing good coal for 16 years, 9 &10 shafts closed, and McBride Tunnel was also near closure. It meant the end of No.5 Brace except that it was decided to develop West Area, Shafts 20 and 21, to keep things going. A new endless haulage ramp had to be built and it had to be ready by 1936. The existing ramps had both come from the east and worked by gravity. The new ramp would come from the west and the skips would be running up hill unless No.5 Brace could be reconfigured. The engineers and carpenters from the mine workshops used their incredible ingenuity to figure out how to set about jacking up the building so it sloped from west to east.

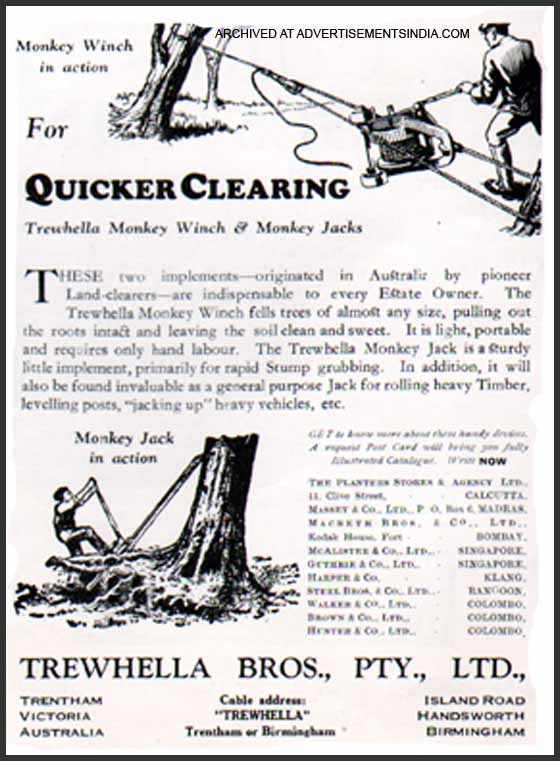

This was a long process where Trewhella jacks were set up on each of the wooden legs on the Brace. The tackle gang foreman, Eric “Knocka” Lewis, would set his men on a row of legs and on his whistle, they would all madly crank until the signal to stop. The same process was repeated on the next row and so on along the Brace.

In 1911, one year later, 9 and10 shafts opened up a fair distance from the Brace near the bird hide and an endless haulage line two kilometres long was established to take the coal past the Powerhouse where the electricity for the mine was being produced – one of the first all-electric braces in the world – around a bend and into No.5 Brace, entering the building via a long ramp to the top storey on the south- east corner. Then when McBride Tunnel area opened up, in 1915, skips entered the Brace from a ramp on the north-east corner via another endless haulage system.

In 1927, after producing good coal for 16 years, 9 &10 shafts closed, and McBride Tunnel was also near closure. It meant the end of No.5 Brace except that it was decided to develop West Area, Shafts 20 and 21, to keep things going. A new endless haulage ramp had to be built and it had to be ready by 1936. The existing ramps had both come from the east and worked by gravity. The new ramp would come from the west and the skips would be running up hill unless No.5 Brace could be reconfigured. The engineers and carpenters from the mine workshops used their incredible ingenuity to figure out how to set about jacking up the building so it sloped from west to east.

This was a long process where Trewhella jacks were set up on each of the wooden legs on the Brace. The tackle gang foreman, Eric “Knocka” Lewis, would set his men on a row of legs and on his whistle, they would all madly crank until the signal to stop. The same process was repeated on the next row and so on along the Brace.

As he was explaining this, John Bordignon was impressing upon me how much strength and stamina it would take from each man to keep frantically cranking for more than two minutes at a time and all at the same time. And they didn’t do it just once because the building had to be lifted incrementally. They would start on the west side again and repeat the process, each time lifting the Brace a little more until it was sloping at the correct angle for the skips to gravitate from west to east once they arrived the three kilometres along the shunt on the endless haulage line. In this way the Brace operated until West Area closed in September 1968, making No.5 Brace the longest continuously operating building at the State Coal mine.

There is no description that I have found yet about how they managed to create the shunt itself at the right height and angle with two tracks one for full skips coming in and the other for empty skips going out on an endless haulage line. Of course, it was all done by hand – there were no Fergie tractors then – but when you think about what could be accomplished with clever practical thinking and innovation, plus horses and coal mining men, the sky is the limit.

When No.5 Brace finally falls away completely, I am sure its ghost will linger and the shunt to West Area will always be there to remind us of a remarkable past.

This essay was first published in The Plod, the newsletter of the Wonthaggi & District Historical Society.

There is no description that I have found yet about how they managed to create the shunt itself at the right height and angle with two tracks one for full skips coming in and the other for empty skips going out on an endless haulage line. Of course, it was all done by hand – there were no Fergie tractors then – but when you think about what could be accomplished with clever practical thinking and innovation, plus horses and coal mining men, the sky is the limit.

When No.5 Brace finally falls away completely, I am sure its ghost will linger and the shunt to West Area will always be there to remind us of a remarkable past.

This essay was first published in The Plod, the newsletter of the Wonthaggi & District Historical Society.