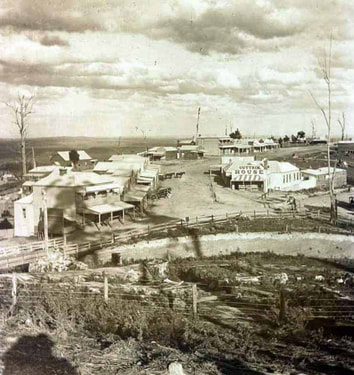

The thriving Outtrim township, complete with railway station, coffee palace and hotels, ca 1897. Photo, John Henry Harvey, courtesy of State Library of Victoria

The thriving Outtrim township, complete with railway station, coffee palace and hotels, ca 1897. Photo, John Henry Harvey, courtesy of State Library of Victoria From The Argus,

31 December 1909

By our Special Reporter

POWLETT RIVER, Thursday –

“The Powlett! The Powlett! Right away for the Powlett!” several coachmen shouted lustily at the Outtrim Railway station as the train drew up to the platform yesterday morning. There was no occasion for the traveller to ask his way. He placed himself with a number of others in the hands of the coachman, and he remained under his care for a number of hours.

The coachman packed his eight passengers aboard the open coach as if they were so many parcels and drove about two- hundred yards up the steep hill to the North Outtrim township. He stopped at the door of the first hotel and said, “You get dinner here.”

31 December 1909

By our Special Reporter

POWLETT RIVER, Thursday –

“The Powlett! The Powlett! Right away for the Powlett!” several coachmen shouted lustily at the Outtrim Railway station as the train drew up to the platform yesterday morning. There was no occasion for the traveller to ask his way. He placed himself with a number of others in the hands of the coachman, and he remained under his care for a number of hours.

The coachman packed his eight passengers aboard the open coach as if they were so many parcels and drove about two- hundred yards up the steep hill to the North Outtrim township. He stopped at the door of the first hotel and said, “You get dinner here.”

A passenger mildly suggested that it would be preferable to run on to Inverloch, 12 miles distant, for lunch, for it was only half-past 11 o’clock, but the coachman became indignant at the idea. He was doing his best to look after the health and pockets of his passengers, and his efforts were not appreciated. A passenger thereupon invited the coachman to have a drink. He condescended and became mollified for the time being.

At the end of an hour the travellers were still advanced only two hundred yards on their journey. The coachman could not be found. In order to delude themselves that they were making some progress to the Powlett River, the travellers mounted the coach, where they made great sport of the wind which tried to blow them collectively over the hilltop. At last on the wings of the wind came the coachman in a great bluster.

“If you fellows had all my work to do, you would never get to the Powlett at all,” he said. “What’s your hurry? You’ll get there tonight. Must move your leg a little over. There. That’s right. Now push over there. Squeeze up a bit in that corner.”

At the end of every sentence the coachman had wedged a parcel into the coach. When he came to the last package, he looked round regretfully, and his gaze lingered for a moment on an empty packing case standing outside a shop. Fortunately, the case did not belong to him.

“You won’t fall out now,” he said with an air of great satisfaction, as he surveyed the coach and its contents. A passenger vainly tried to move his foot as the break groaned down the long hill to the Inverloch road. It is a never-to-be-forgotten road.

Several of the passengers were miners returning to the mines after a holiday. One was a saw miller, with an eye to starting a sawmill on the field. Another was a businessman going to have a look at the prospect from his point of view. One miner had under the seat a bag of green peas and French beans, and a Christmas present for his mates. “It’ll be a change from the tinned stuff,” he said, “and it will show them that I did not forget them when I was away.”

The miners talked of distant fields: “Were you ever at Cobar? Were you ever at Kalgoorlie? Did you know Jack Rafferty?” were some of the questions by one to the other. Soon the talk was all about Western Australia. It was the dust which introduced the subject.

There is a big traffic now between Outtrim and Inverloch, and the track is cut into fine white sand several inches deep. The sand reminded the miners of Western Australia. “It is like the road from Southern Cross to Mount Jackson,” said one man. A strong westerly blew the white sand down the long road in one long cloud, which cut sharply into the dreary forest of messmate, and the marshy flats covered with button grass and other hungry weeds, and the scrub in the distance. A portion of the sand cloud stretched higher into the sky, and further into the forest. It marked the progress of a bullock team hauling another slice of Outtrim to Powlett River, viz., a three-roomed weatherboard house.

The passengers in the coach were slowly losing all resemblance to their former selves. One who left the train with a black beard looked grey with age; his blue serge suit was a dirty white. Every face was covered with a thick mask. One had to look hard at a man to identify him from his fellow travellers. The conversation came to a standstill. It was inviting suffocation to open one’s lips. The only word spoken for several miles was the driver’s occasional encouragement to his horses, “Get erp.”

At Inverloch all the winds of the ocean appeared to have been let loose. There must be 200 bullocks at work between the Powlett River and Inverloch, and the track for the whole 10 miles consists of loose sands. The streets of Inverloch are also unmetalled. The people of the port faced the dust with equanimity. They regard it as the product of traffic and the representative of thriving business. They shut their street doors to the dust and make the best of that which forces its way through the crevices. Inverloch is a busy port now.

At the end of an hour the travellers were still advanced only two hundred yards on their journey. The coachman could not be found. In order to delude themselves that they were making some progress to the Powlett River, the travellers mounted the coach, where they made great sport of the wind which tried to blow them collectively over the hilltop. At last on the wings of the wind came the coachman in a great bluster.

“If you fellows had all my work to do, you would never get to the Powlett at all,” he said. “What’s your hurry? You’ll get there tonight. Must move your leg a little over. There. That’s right. Now push over there. Squeeze up a bit in that corner.”

At the end of every sentence the coachman had wedged a parcel into the coach. When he came to the last package, he looked round regretfully, and his gaze lingered for a moment on an empty packing case standing outside a shop. Fortunately, the case did not belong to him.

“You won’t fall out now,” he said with an air of great satisfaction, as he surveyed the coach and its contents. A passenger vainly tried to move his foot as the break groaned down the long hill to the Inverloch road. It is a never-to-be-forgotten road.

Several of the passengers were miners returning to the mines after a holiday. One was a saw miller, with an eye to starting a sawmill on the field. Another was a businessman going to have a look at the prospect from his point of view. One miner had under the seat a bag of green peas and French beans, and a Christmas present for his mates. “It’ll be a change from the tinned stuff,” he said, “and it will show them that I did not forget them when I was away.”

The miners talked of distant fields: “Were you ever at Cobar? Were you ever at Kalgoorlie? Did you know Jack Rafferty?” were some of the questions by one to the other. Soon the talk was all about Western Australia. It was the dust which introduced the subject.

There is a big traffic now between Outtrim and Inverloch, and the track is cut into fine white sand several inches deep. The sand reminded the miners of Western Australia. “It is like the road from Southern Cross to Mount Jackson,” said one man. A strong westerly blew the white sand down the long road in one long cloud, which cut sharply into the dreary forest of messmate, and the marshy flats covered with button grass and other hungry weeds, and the scrub in the distance. A portion of the sand cloud stretched higher into the sky, and further into the forest. It marked the progress of a bullock team hauling another slice of Outtrim to Powlett River, viz., a three-roomed weatherboard house.

The passengers in the coach were slowly losing all resemblance to their former selves. One who left the train with a black beard looked grey with age; his blue serge suit was a dirty white. Every face was covered with a thick mask. One had to look hard at a man to identify him from his fellow travellers. The conversation came to a standstill. It was inviting suffocation to open one’s lips. The only word spoken for several miles was the driver’s occasional encouragement to his horses, “Get erp.”

At Inverloch all the winds of the ocean appeared to have been let loose. There must be 200 bullocks at work between the Powlett River and Inverloch, and the track for the whole 10 miles consists of loose sands. The streets of Inverloch are also unmetalled. The people of the port faced the dust with equanimity. They regard it as the product of traffic and the representative of thriving business. They shut their street doors to the dust and make the best of that which forces its way through the crevices. Inverloch is a busy port now.

“Can you get a bed?” said an astonished hotelkeeper in answer to an inquiry by one of the travellers by coach. “I have not a bit of room to spare!” The passenger got a similar answer at a second hotel. He went through to Powlett River, and at 5 o’clock started on a four-mile walk to Dalyston, still in search of accommodation.

The travellers, when they reached Inverloch, were sorrier looking men than the dirtiest tramps who ever carried swags, and they still had ten more miles to go. “You’ll get it worst still,” was the disconsolate news they received when they prepared to resume their journey. The news was too true. The wind was right in their faces and the road was more cut-up than before. It was impossible to see more than a few yards in front of the horses, and a stoppage had to be made for fear that the horses would run into an outward-bound bullock wagon. The country behind the coach was swallowed up in an onrushing, enveloping cloud of irresistible force. At times glimpses could be seen of the sea with its cool, green, refreshing water, flecked by white foam. It was a tantalising picture, across which the dust speedily drew a veil. The suffering passengers buried their faces in their arms to protect their smarting eyes, but nothing could keep out the dust.

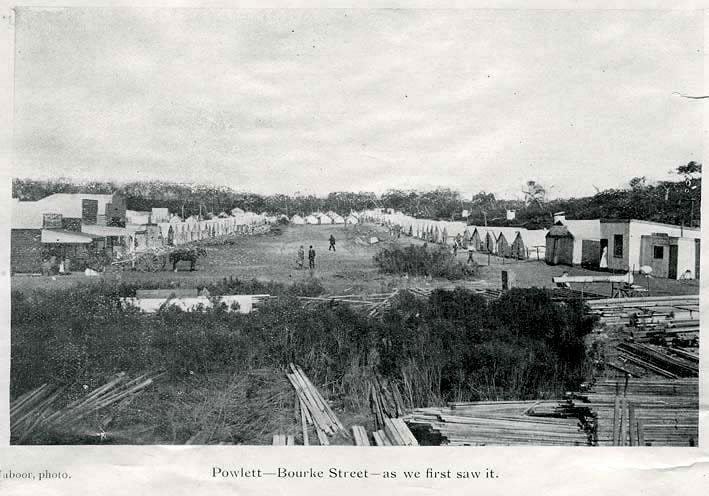

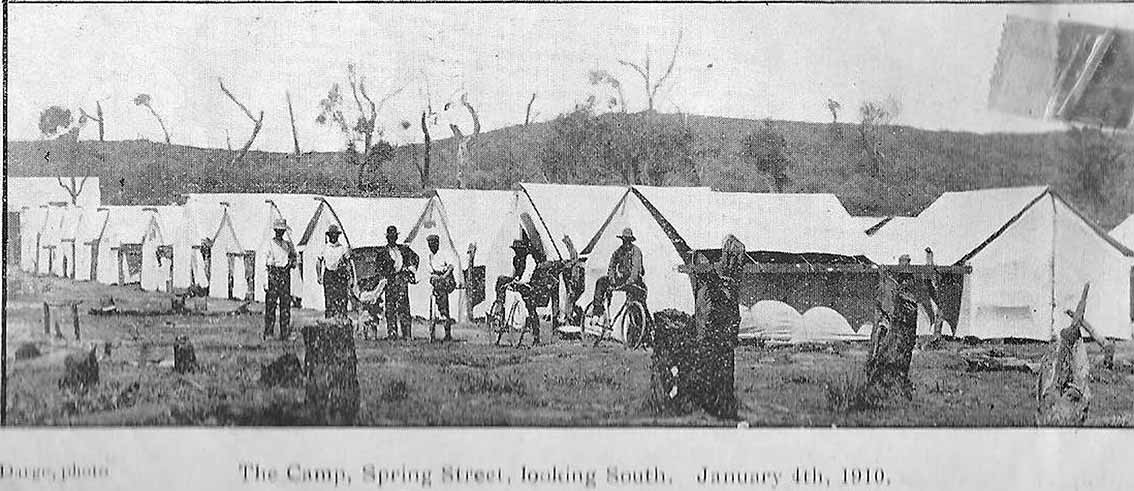

At last, from a slight rise, the township of Powlett River burst into view, and the dust disappeared. Bloodshot eyes lit up as best they could and gazed on one hundred tents systematically laid out. The tents flapped a welcome in the wind, looking like so many half-inflated balloons straining at their ropes. Miners popped their heads out of doors to regards the new-comers. The returned miners looked round for changes in the township and saw with pride that it had grown in the days they had been away. It looked a peaceful, reposeful camp in early evening.

The travellers, when they reached Inverloch, were sorrier looking men than the dirtiest tramps who ever carried swags, and they still had ten more miles to go. “You’ll get it worst still,” was the disconsolate news they received when they prepared to resume their journey. The news was too true. The wind was right in their faces and the road was more cut-up than before. It was impossible to see more than a few yards in front of the horses, and a stoppage had to be made for fear that the horses would run into an outward-bound bullock wagon. The country behind the coach was swallowed up in an onrushing, enveloping cloud of irresistible force. At times glimpses could be seen of the sea with its cool, green, refreshing water, flecked by white foam. It was a tantalising picture, across which the dust speedily drew a veil. The suffering passengers buried their faces in their arms to protect their smarting eyes, but nothing could keep out the dust.

At last, from a slight rise, the township of Powlett River burst into view, and the dust disappeared. Bloodshot eyes lit up as best they could and gazed on one hundred tents systematically laid out. The tents flapped a welcome in the wind, looking like so many half-inflated balloons straining at their ropes. Miners popped their heads out of doors to regards the new-comers. The returned miners looked round for changes in the township and saw with pride that it had grown in the days they had been away. It looked a peaceful, reposeful camp in early evening.

The time was then shortly after 5 o’clock. About an hour and a half later a man presented himself to the mine officials in search of work. He wore a dark suit, but he was not dirty in appearance as the occupants of the coach, who had reached the township before him. He had walked from Outtrim to Inverloch, thence to Powlett River, 22 miles in all. He did know the shorter route of 18 miles. He walked with machine-like stride, with a heavy swag on his back. He wanted work. He had staked everything on getting work. He had journeyed nearly 200 miles to the field and during the last 22 miles, he had spent his last shilling. Mr McKenzie gave him a job today. He had gone off to work a light- hearted man.

Strictly speaking, he should not have been given the job, for there are 4,000 men on the register of applicants for work on the mines. By all that is fair and honest, however, that miner – and by all accounts he was a skilled man – has earned his positions. Mr McKenzie, day after day, is being appealed to by men, who have travelled from distant parts of the State in search of work. It is an unpleasant office to have to refuse employment to such willing workers, but it is the duty of the officials to keep to the register of applicants, and they hope the men will refrain from journeying to the field on the off-chance of getting employment.

Afternoon tea, with Mr D.C. McKenzie and Mrs McKenzie as hosts of a company including a party of yachtsmen from San Remo, was an enjoyable experience after the journey through dust. Then followed a luxurious wash and an equally luxurious shave. The barber is a Scotch-man. His arrival in Australia is contemporaneous with the rise of the fields. He comes to your tent and you lie on the broad of your back on the bed. He adjusts the pillow to a nicety, and you close your eyes and forget about the dust.

“My hands don’t look clean for a barber,” he says apologetically. You look at his hands and see that they are stained black. “That is from coal mining,” he confides. “I had two days at it.” And he shook his head in a sadly reflective fashion. He is a better barber than a coal miner.

Many people are grateful for that fact, but everyman is a good workman at the camp. The cook at the Officials’ Mess was told late on Christmas morning that ten visitors had arrived for dinner.

“Very well,” he said, “dinner will be ready in half an hour.”

There were five courses, and there was ice cream at the finish. They carried up the camp organ from the canvas church to the officers dining room last evening, and, by the light of a hurricane lamp, the company sang Alexander’s hymns and choruses and finished up at midnight with a dance.

The oil engines at the pit, however, did not close at midnight. They are always at work, except on Sundays. Their steady puffing could be heard above the wind, and the bright acetylene gas lamps lit up the darkness of the western sky.

This story was originally published in The Plod, the newsletter of the Wonthaggi & District Historical Society.

Strictly speaking, he should not have been given the job, for there are 4,000 men on the register of applicants for work on the mines. By all that is fair and honest, however, that miner – and by all accounts he was a skilled man – has earned his positions. Mr McKenzie, day after day, is being appealed to by men, who have travelled from distant parts of the State in search of work. It is an unpleasant office to have to refuse employment to such willing workers, but it is the duty of the officials to keep to the register of applicants, and they hope the men will refrain from journeying to the field on the off-chance of getting employment.

Afternoon tea, with Mr D.C. McKenzie and Mrs McKenzie as hosts of a company including a party of yachtsmen from San Remo, was an enjoyable experience after the journey through dust. Then followed a luxurious wash and an equally luxurious shave. The barber is a Scotch-man. His arrival in Australia is contemporaneous with the rise of the fields. He comes to your tent and you lie on the broad of your back on the bed. He adjusts the pillow to a nicety, and you close your eyes and forget about the dust.

“My hands don’t look clean for a barber,” he says apologetically. You look at his hands and see that they are stained black. “That is from coal mining,” he confides. “I had two days at it.” And he shook his head in a sadly reflective fashion. He is a better barber than a coal miner.

Many people are grateful for that fact, but everyman is a good workman at the camp. The cook at the Officials’ Mess was told late on Christmas morning that ten visitors had arrived for dinner.

“Very well,” he said, “dinner will be ready in half an hour.”

There were five courses, and there was ice cream at the finish. They carried up the camp organ from the canvas church to the officers dining room last evening, and, by the light of a hurricane lamp, the company sang Alexander’s hymns and choruses and finished up at midnight with a dance.

The oil engines at the pit, however, did not close at midnight. They are always at work, except on Sundays. Their steady puffing could be heard above the wind, and the bright acetylene gas lamps lit up the darkness of the western sky.

This story was originally published in The Plod, the newsletter of the Wonthaggi & District Historical Society.