Author Christine Bell with Sam and Claire Gatto, members of

Author Christine Bell with Sam and Claire Gatto, members of the Wonthaggi Historical Society.

By Catherine Watson

WHEN children’s author Christine Bell visited the State Coal Mine museum in Wonthaggi in 2008 she was, like many visitors, in search of her family history.

At the museum shop that day she bought two replicas of the mining token of her great-grandfather, John McConochie. Later she strolled the streets of Wonthaggi and called into the museum,at the old railway station, where she found a treasure trove of newspapers, maps and artefacts. Volunteers were happy to help her fill in the gaps in her knowledge of her great-grandparents’ immigration journey that brought them to Wonthaggi in 1910.

WHEN children’s author Christine Bell visited the State Coal Mine museum in Wonthaggi in 2008 she was, like many visitors, in search of her family history.

At the museum shop that day she bought two replicas of the mining token of her great-grandfather, John McConochie. Later she strolled the streets of Wonthaggi and called into the museum,at the old railway station, where she found a treasure trove of newspapers, maps and artefacts. Volunteers were happy to help her fill in the gaps in her knowledge of her great-grandparents’ immigration journey that brought them to Wonthaggi in 1910.

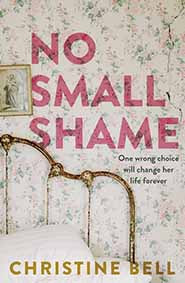

Last year, she published her first adult novel, No Small Shame, a rollicking family saga set in large part in the new mining town of Wonthaggi.

And last month she returned to the museum to fill in the gaps in her own story. “I had no clue how Wonthaggi was going to get into my blood,” she told members of Wonthaggi’s Historical Society during her talk.

And last month she returned to the museum to fill in the gaps in her own story. “I had no clue how Wonthaggi was going to get into my blood,” she told members of Wonthaggi’s Historical Society during her talk.

Conditions in the Wonthaggi mines were among the most difficult

Conditions in the Wonthaggi mines were among the most difficult in the country. Miners in number 20 shaft, 1930s before the

explosion that killed 13 men. Photo: The Age.

“From the moment I stepped into the museum, and everywhere I went in Wonthaggi, it was like a connection. A little voice kept saying to me ‘There’s a story here’.”

“I could focus on the novel I was then working on – and then Mary turned up with her very distinct voice, talking insistently in my ear until I had no choice but to give over and write her story.”

Mary O’Donnell, the central character of the story, is married to Liam, a Scottish miner who has migrated to Australia for a new life. To his despair, he finds himself back working in a mine in Wonthaggi. He hates the wet boots, the stink, the terror.

“I could focus on the novel I was then working on – and then Mary turned up with her very distinct voice, talking insistently in my ear until I had no choice but to give over and write her story.”

Mary O’Donnell, the central character of the story, is married to Liam, a Scottish miner who has migrated to Australia for a new life. To his despair, he finds himself back working in a mine in Wonthaggi. He hates the wet boots, the stink, the terror.

| In the novel, Liam tells Mary: “Do you know that I think of you sometimes when I’m down the pit in the dark. How lucky you are out in the daylight. Sometimes when the trees are talking underground*, I know I’m not going to heed their warning. I want the roof to come tumbling down and bury me so I never have to pick up my token another day of my life.” Bell did much of her original research in the State Library, reading the Wonthaggi newspapers of the time on microfiche. That was until Carolyn Landon, a member of the historical society and a fellow writer, took pity on her and sent CDs of the Sentinel Times newspapers from 1909-12. Of course there was far too much detail to include in the book but Bell said it was helpful to have the pictures and sounds and smells of Wonthaggi in her head as she wrote. “I’m a strong advocate of walking the ground for my research.” She found herself obsessed with researching Wonthaggi and its Scottish equivalent, the mining village of Bothwellhaugh, connected by a steamship voyage to Australia in 1910. She believes the far superior housing in Wonthaggi would have been a great incentive for her great-grandparents. “My great-great-grandmother had lost five childen. The loss of babies due to influenza and diptheria was very common for people living in the slums and tenement rows.” She’s amazed at how many people have contacted her since the book came out to tell her they have a connection with Wonthaggi. Her research – and her novel – drew warm applause from her audience of local historians last week, both for the accuracy of the Wonthaggi section and her epic family drama. On her part, Bell said she could not have written it without the generous help of the historical society members, in particular Sam Gatto and John Bordignon. “Dedicated historical societies, museums and archives are so important,” she said. “Without them, future writers will struggle.” * The miners use the expression “when the trees are talking underground” to refer to premonitions of a mine collapse. | Under the radar Author Christine Bell's great-grandfather John McConochie emigrated from a small Scottish colliery town called Bothwellhaugh to work at the State Coal Mine. Six months later his wife Mary and their children followed as “nominated passengers”. Christine’s grandmother, Alice, was 10 years old. From family stories, she knows that when they first arrived in Wonthaggi they lived in a tent in someone’s back yard in Hagelthorn Street for six months before moving to their own house in Ivor Street. “My great-grandmother apparently carried on for the whole six months. ‘I’ll never forgive you for bringing me all this way to live in a tent!’ “I doubt my grandparents were widely known in Wonthaggi. They were not political or public figures. They’re hard enough to find in any records as John was illiterate. Any records he initiated, as in the State Coal Mine, his name is generally spelt incorrectly. John would have said ‘Ae.’ Near enough. “By the time I wrote No Small Shame, I’d missed my opportunity to quiz my grandmother on her life in Wonthaggi. We never think to ask the questions we should ask until it’s too late.” |