Many of the mines were much shallower - the miners couldn't stand upright.

Many of the mines were much shallower - the miners couldn't stand upright. The opposite extreme was Kirrak Area where they had some of the deepest tunnels and they worked in heat about 35° to 40° with 80% humidity. It was murder.

At Kirrak, Dad and his mate, Blueboy, were putting a connection between two main tunnels that they called a ‘cut-through’. It was in an area they called Siberia. There they were working in a cut through about a metre high and the heat was so intense that they were getting hives all over themselves. You could go in there and work for half an hour/three-quarters of an hour and then get out in better air to recuperate for a while before they had to go back in again. The backs of their knees would just split open from all the sweat as they were kneeling while working. They had to take salt tablets while they worked in that section. Well, that’s the way it was.

“Well, I’m fishin’.”

“What the… What are you fishing for??”

“Well, I’m fishin’ for wet pay!”

His point was made.

Sometimes when miners drilled a hole in the stone in order to set a charge, the dust that came out was dry and if there was water, as there always was in Western Area, the dust wouldn’t sink but would float on the water making a puddle look like solid ground. It was a great joke to lure deputies to step on what seemed like solid ground and watch them sink up to their ankles. They’d come out soaking wet and yelling: “What’s going on here!?!”

The miners would ask them for their wet pay there and then.

The wet conditions in Western Area also meant that the miners had to put up with the ground heaving. Mud stone, as they called, when it got really wet, expanded. So, the miners might leave the tunnel one day with all the bords and rail in order and come back the next day with the tunnel having shrunk from the expanding mudstone. They would have to rip up the rails and sleepers and dig out the floor to maintain the road height and then re-set everything before they could hew any coal.

Well, Danny Carr told about one section of Western Area that was like this for more than a month. It was just total stupidity because no matter how much they dug out, the miners would have to do the same over and over again, day after day. Finally, they just gave up and closed that section of the mine down.

Wonthaggi miners sort coal.

Wonthaggi miners sort coal. As the miners’ extracted coal from the pillars, which were approximately 20 metres square, they would put in timber props to support the roof and prevent cave-ins. Once they had finished extracting the coal, the timber props were withdrawn and the timber re-used further down the line. Timber drawers would come in during the night shift and use what they called a Sylvester, which was really a large fence strainer. The Sylvester was anchored in the tunnel and steel cables wrapped about the props in the pillars so they could pull out all the timber safely and recycle it. They re-used the timber as much as they could.

After this operation, sometimes that roof caved in straight away, but sometimes it would just sit there for two or three weeks. Eventually, it would give, and when it did, it made a hell of a noise as you can imagine with all that stone caving in. Just imagine a young fellow newly working in the mine and he hears all this rumbling for the first time and if it is a dry area all this dust comes with it flying up the tunnel, he would be off, running to save his life, frightened out of his wits. The older miners would laugh their heads off, but, in fact, they would be remembering their first time running for their own lives.

Tales of the underground Part 1

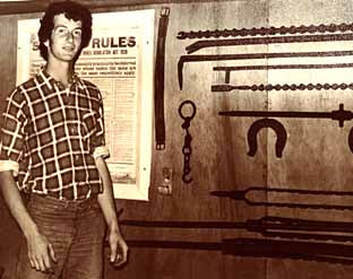

A young John Bordignon photographed not long after

A young John Bordignon photographed not long after the closure of the State Coal Mine in Wonthaggi.

THE following stories are part of Wonthaggi’s culture. For most of us – those of us who are curious about where we live – these stories are familiar and well loved. In my relatively short experience here, the best place to hear these stories is at the Railway Station Museum on weekends or hanging around after a Historical Society meeting or at the State Coal Mine where the guides, who take you into the mine itself, can talk a blue streak.

People love it when John Bordignon gets started. His fascination with the mines and miners of this town goes back to when his dad took him down into the tunnels at Kirrak not long before the final closure when all the ponies and skips and miners were winched up for the last time and the Wonthaggi Mines became the stuff of legend.

The following is essentially a transcription of the stories John told in his 15-minute talk to a large and enthusiastic group late this summer. He started on time at 11.30am but his audience was so rapt that he didn’t take a breath until the mine whistle blasted him into silence half an hour later.

For many years I worked at the State Coal Mine Heritage Area, as many of you know. Along the way I worked with many of the old miners who had tales to tell. We used to have a lot of fun, especially at morning tea-time, when the men would start with their yarns. Most of the stories I will tell today are ones I heard the old timers tell as they guided tours down in the mine. Some of these stories are true and some of these stories have elements where the truth got in the way of a good story. So, I will tell you the stories as they were told to me.

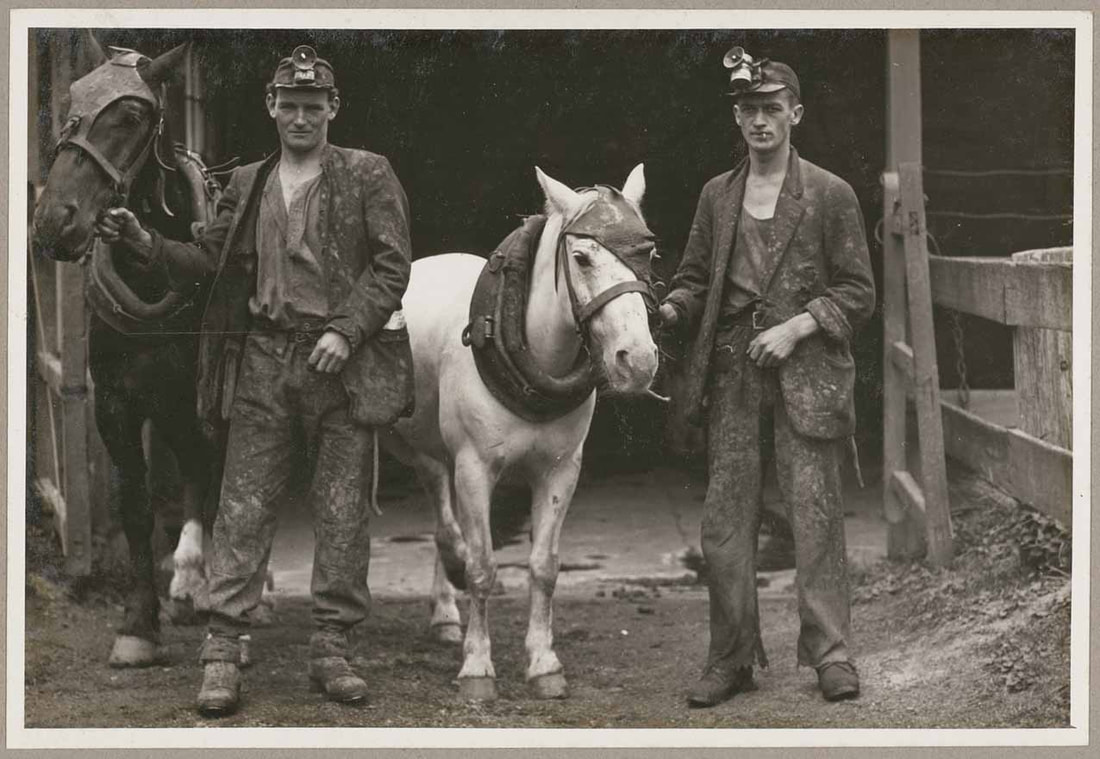

The pit ponies:

The ponies were an integral part of the mine. The wheelers worked with them and they became very attached to those ponies. The wheelers were characters in their own right, but so were the ponies. One pony that really stands out is Porky. Porky was a bit of a cantankerous old pony. He’d bite you and he’d kick his wheelers. If you were going along a tunnel and you called out to him to go right, he’d go left and derail the skip. He would then go along the roadway and come to a narrow spot and decide he would not go through. His wheeler, one day, came along the side of Porky in an attempt to get ahead of him and pull him through. So, Porky pinned him to the side of the wall. The old wheeler was stuck there so he yelled out to get some help. Another wheeler comes along and says, ‘I’ll walk along the other side of the pony and get him.” So just as he starts to move along the clear side, Porky puts his rump over and traps that miner as well. Both men were stuck. That’s the kind of pony he was.

It actually got to the point where no one wanted to work with Porky. Nobby Smith, who was the head stableman at the mine, managed to move him off to the speed coursing track where the greyhound races used to be. Porky’s job was to drag the smudger around the track for maintenance work. Eventually, the track closed down and so they had to get Porky back to the mine. They brought him back to Western Area in the truck and the minute they let him out he walked straight into his old stall as if he had been there yesterday.

Sometimes they would also put sand on the rails so the wheels would not slide quickly. Well, this day, Dad missed the sprag and also missed the second go at spragging on the next wheel. Socks heard that Dad had missed so he took off in an attempt to outrun the skip, but Dad knew there was a door halfway down the descent and he thought Socks would be tripped up and killed by the skips when he hit it. Dad ran after Socks knowing he couldn’t get to the door to open it before the horse got to it and dreading what he might see, but sure enough, Socks had outrun the skip, somehow shouldered his way through the door and went on until he got to the flat on the other side where the road levelled off. When Dad got to him, there was Socks quietly waiting for him to catch up. Remember, this was done in the dark since there were no lights in the tunnel. Tells you something about the instincts of those ponies. [And makes you wonder what Socks was thinking about John’s Dad right at that moment.]

Jack Keltie, another one of our guides at the Coal Mine who had been a wheeler, was telling us one day about one of his ponies. He said that some of the ponies would actually back up if a sprag was missed and lean against the skip to stop it from moving. This day, the pony had braced himself against the skip but he couldn’t get enough traction on the track to hold it and so he slid down the incline sitting on the skips’ buffers. When I heard this story I thought it might be a bit of a stretch but another miner, corroborated the story. He said, ‘Yeah, I was actually in a side tunnel and I saw the pony sliding past sitting on the skip’s buffers.’

Old Harry Sainsbury one day told the story about how he used to come to a wooden door which he would open and call his pony through. This day, his pony wouldn’t budge. Harry coaxed and coaxed and coaxed, but the pony wouldn’t go through so Harry used a few more adjectives that the horse would understand. Suddenly the pony bolted through the doorway, but no sooner had he done that than the roof caved in. The horse was trying to tell his wheeler of the danger by not moving but gave up and bolted through. luckily the pony wasn’t hit by any stone, saving both himself and his wheeler.

Here is a story from 20 Shaft: The miners were having their Crib [lunch]. Sometimes when you finished your food, you’d sit back and have a rest. One of the wheelers was having a little kip and all of a sudden they heard a pony running like a bat out of hell. The miners switched their lights on and looked up seeing a bit of dust sifting out of the roof and saw three rats run past. They cried out, “We’d better get out of here!” and sure enough not long after they had taken off the roof caved in.

Rats in the mine were the miners’ friends. They were the alarm system. If they were suddenly on the move, you knew something was wrong and you’d better move, too. No one worried too much about working near rats. The only problem with them might be after the holidays, say for the few weeks at Christmas time when the mine was always closed. Then the rats were glad to see the miners because they hadn’t had anything to eat for a while and they would start climbing their legs trying to get some food. Because they had been starving there was always evidence of the rats turning on each other as there were uneaten heads lying about and the smell was a bit strong. But the miners knew they were an important part of mine safety.

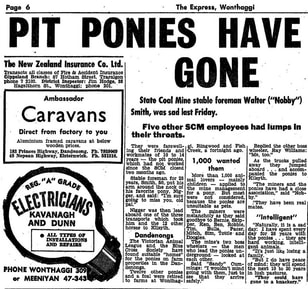

The Express, Wonthaggi, February 20 1969 - two months after the State Coal Mine closed.

The Express, Wonthaggi, February 20 1969 - two months after the State Coal Mine closed. Shimma Donohue used to pack an extra sandwich in his crib. When it was crib time and he sat down to eat, his pony would sidle up to him and sit back on his haunches and wait for Shimma to give him his bit of sandwich and then he was happy.

Danny Carr worked at the mine workshops, which was situated where DonMix is now. He regularly had to come down into the tunnels for maintenance duties. One time he was in Western Area and witnessed the following: Pit ponies knew their way around the tunnels, so they knew how to get around, even in the dark. Ponies would pull the skips along the tunnel at a normal pace until, at certain spots, they would begin to race along. One pony in particular was very clever and always knew when he got to a certain rise that there was a bend in the road and the only way to get those skips up to the top was to go for it. His hooves would hit the rails and sparks would flash out from his metal shoes until he went round the sharp bend at the top of the rise and slowed down to his normal pace while the wheeler caught up with him.

This essay, the first part of a three-part series, was first published in The Plod, the newsletter of the Wonthaggi Historical Society. Parts 2 and 3 will be published in future editions of the Post.