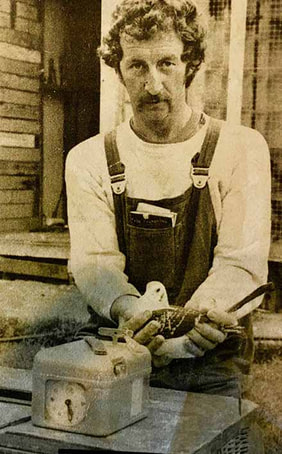

Rod Churchill became absorbed by the intricacies of pigeon racing

Rod Churchill became absorbed by the intricacies of pigeon racing By Rod Churchill

I’LL TELL a little story. I was born on a farm at Kilcunda. We had pigeons on the farm and so I brought a few of them into Wonthaggi when my parents sold the farm. I started playing cricket with the Workmen’s Club. There were a number of people in the team who raced pigeons.

It took me a while to become interested in pigeons because I was really into cars, racing cars. Back in those days, I had the fastest car around. If you had a fast car, blokes used to come from other towns to see if they could beat you. We used to go out to the Korumburra Road, which was straight and flat and a quarter mile. One Saturday night I was dragging this fellow from Traralgon. There would be cars on either side of the road and we would be dragging down the middle of the road. Well, I finished in front and when I got to the end of the run there were these blue lights flashing. All of a sudden I was pulled over. And who got out of the car but Terry Weir and Billy Studham, two Wonthaggi Policemen. I played cricket with them. And I knew they raced pigeons.

I said, “No fire, Bill.”

He said, “Well you were in a bloody hurry. Where were ya going?”

I said, “I was just draggin’ these blokes from Traralgon.”

He said, “Well, you got two options. You lose your licence and you go to jail or you take up racing pigeons.”

I said, “I’ll take up racin’ pigeons.”

He said, “You sure? Okay then. You be at my place tomorrow before 9 in the morning. You come two minutes late and I’ll come find you and lock you up.”

I got to his place at quarter to nine. I was sitting out the front when he came out and gave me three pair of pigeons and to this day, I thank him for saving me. I got out of cars and concentrated on the cricket and the pigeons.

He was saving the Pigeon Club as well as me because back then in the early 70s when Billy Studham was president the pigeon club had nearly folded. Through the Workmen’s Cricket Club and down at the Workmen’s with people like Johnny Baker, Jimmy McCulley, Kevin Williams … we got it fired up again.

Here’s what happened. A bloke named Jack Brosman came up to me at the bar one night. He said, “You fair dinkum about this racin’ pigeons? Right!” He put this big jar on the table that’s got money in it. I asked him what it was and he said, “That’s what’s left of the Wonthaggi Pigeon Club. There’s $68 in there.”

So that’s how we started. Johnny Baker had all the club gear in the garage at the back of his place behind the hospital. And so we went there and started again. The membership grew. We moved to where Warren Smith was behind the Bakehouse where there was a tin shed. We got all the baskets and we went down to Melbourne and bought new pigeons, spoke to different guys, handed out the birds for them to take care of plus we got a few of the old clocks and that’s how it started.

The club got bigger. We had some really good blokes who got involved in it. We used to have progressive dinners and people who weren’t even members came along. It was a really good group and we all got along. We decided we had to start looking for some land where we could build a real clubroom.

One of the guys who was racing pigeons with us was Milton Sibley. He was on the Council. He came over to the club one night. Porky (Jim) Dowson and I were there, President and Vice-president. Sib said to us that he had been through all the Council records and there was a bit of land we might be able to use up near McMahon’s oval. Up we go to see an area that had been the old cricket club rooms about 60 x 20 ft. and we thought this is all right. We thought: we raise $2000 and get another $2000 through the Council with Sib’s help.

Off we go to a meeting and Jack Clancy was a Councilor. He said, “What do you want?”

We said, “We want $2000 for a pigeon club.”

He said, “How long will it take you to build a new shed?”

We said, “Four Weeks.”

He was surprised and said, “If you can do it in four weeks, I move that we give you the money.”

We said, “All right! We’ll start next weekend.”

Donmix donated the concrete. The cement was delivered free of charge. Bricks were donated. Timber was donated. We laid the cement first of all, starting early in the morning. Two of us wore gumboots so we scrambled in the muck with shovels spreading it out and then John Lee did all the screening off for us. He had his own tools. We stayed there having a few drinks waiting for the concrete slab to go off when a female Labrador being followed by a pack of male dogs went straight down the middle of the wet cement. We thought, “Here we go!” Mick Sleeman, Jock Macdermid, went after them. After we chased them out we had to rush to smooth it all off again.

The next weekend Porky Dowson and Mick Sleeman did the brick work. We did the labour for them. We put the walls up. Rod Farrell and others helped puts the roof on and with all the help and everyone working we had the shed up within four weeks.

Probably the only money it cost us was Al McFadden. He said, “I’ll paint it but you supply the grog.” I think it cost about four or five slabs of VB. That was just the local town people that were like that all working together. No permit of course. Solid brick, a flat roof, you don’t need a permit. Everything was donated: the sink, the plumbing, hot water service, even the carpet. The council charged us $1 a year to use the land our shed was on. I don’t think we ever paid them.

There was a fellow who was just mates with some of the fellows, not a pigeon man, and he saw what we were doing and he offered to lend us the $2000 interest free. That’s what Wonthaggi people are like. You know?

I don’t know much about the older clubs from the 1930s, but I know some of them learned to fly pigeons in the army. Sometimes they would talk about the old days at the Workmen’s. We kept all the old trophies in our clubhouse.

We all kept our pigeons in lofts behind our houses. Once a starting place for a race was decided, we would bring the birds to the train station in baskets. And the Station Master, Kevin Grisham, would put the pigeons on the train. They would go to places like Ballarat, Horsham, Bendigo. We didn’t go with them. We watched them being put in the guard’s car. They were big wide baskets, and on the sides of them there would be a drinking tray with a note on to remind the stationmaster to please water the pigeons when they got to their destination. We’d also have a note on the basket telling the stationmaster to release the pigeons at 9 o’clock start. If the train trip took overnight, we would make sure the birds were fed and watered at certain times. Most important is water. A pigeon can go without food, but it can’t go without water.

The pigeons are registered in your name. They wear bands that stay permanently on their leg. It’s put on the pigeon when it’s 10 days old. That’s got a number on it and that pigeon is registered in your name. They used to have a rubber attached to the band that you have to bring to the clock at the finish. The clock would be set for 9 o’clock but it wouldn’t be going until first bird, sometimes out of hundreds, comes home and the rubber band is slotted into the clock and it turns on.

It’s when the pigeon lands at his loft that the owner grabs the rubber and races it down to the Workmen’s. There are stories here about people up on Graham Street. George Mortimer? He used to have a big A-framed pigeon loft. There were a few more up the street there. Of course, they’d be biking down the street at a fast pace and out would come a stick through the fence to skittle the bikes. That’s what they used to do. You hear all these stories. Those are from the old days.

Sometimes you’d have to wait hours for your bird to come back. We’ve all done that. I played football for years. I remember, when I was young, I had to con me mum or dad to wait at home for the pigeon to come home while I played in the game. I’d be playing, and at the same time I’d be watching, looking up in the sky, waiting for them to come over.

Pigeons can fly six hundred miles in a day. The biggest problem is they need water. The racing pigeon is special. They get the best treatment. They will race until they drop. I had a pigeon, a real champion, who flew his heart out. It was a sad day when I found him. There are all sorts of ways you can lose a pigeon. Through storms, for instance. Falcons will attack them. A pigeon can see for 25 miles. But it can only see down, not up. So the falcon comes from above.

We used to race to Tassie. The Tasmanians would send their birds over and I was in charge of tending to them and letting them go on time. Pigeons can fly so high they are specks in the sky. They look for no wind and find it very high. 90% of the pigeons will come home in a group.

When we were told the trains were closing down we didn’t know what we were going to do! We tried to work with other clubs down the line. I finished in Wonthaggi in 1984.

This is an edited version of Rod Churchill’s talk to the Wonthaggi Historical Society In March 2019. It first appeared in The Plod, the society’s newsletter.