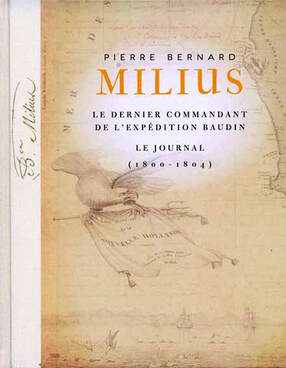

The diary of Captain Pierre-Bernard Milius gives us a rare window into the world of the Bunurong people in Bass Coast before European settlement.

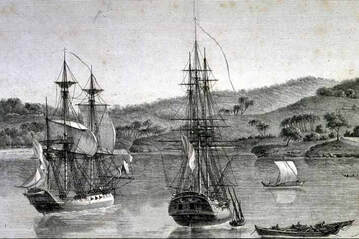

The diary of Captain Pierre-Bernard Milius gives us a rare window into the world of the Bunurong people in Bass Coast before European settlement. IN 1802, Napoleon Bonaparte sent two ships out to Australia as part of the Voyage of Discovery to the Southern Lands, led by Nicolas Baudin. In April, a party of explorers from one of the ships, Le Naturaliste, surveyed Western Port.

Four years earlier George Bass and his crew had seen fires burning on the cliffs on the eastern side of the bay. Now the French explorers finally met with Bunurong people, close to what is now Settlement Point at Corinella.

The following extract, taken from my thesis, is based on diaries of the expedition.

‘Toolumn’s people, who were connected with the Bonkoolawal (Bass River) clan, may have seen the pale men in George Bass’ whale boat sail into Warn-mor-in. Bass named it ‘Western Port’, ‘from its relative situation to every known harbour on the coast.’ ‘Bass River’ was the name given to the stream the Bonkoolawal called ‘Yallock Weardon’ and the island ‘Corriong’ became ‘Phillip Island’ after the white peoples’ Governor.

…

Casting off from ‘Isle des Francais’ on April 11, 1802, Captain Pierre-Bernard Milius and those with him saw thick smoke on Settlement Point and were beckoned by Aboriginal men to come ashore and climb a 50 foot cliff to meet with them. Milius recorded the following in his journal:

| Not one of them dared to descend though they had called to us. They babbled a very long time, without our being able to understand what they desired. Believing, nevertheless, that they were inviting us to leave our clothing, and that they would descend the cliff to get it, I took off my socks and my shirt. That appeared to satisfy them. I commenced to climb the cliff and as it was steep they indicated plants by which I should pull myself up. In vain I made demonstrations to induce them to reach out a hand to me. They showed the same mistrust. When I was nearly to the top, I pretended not to be able to climb further and extended my arms towards them, as though to supplicate them to save me; but none advanced to help me. Grey cells were working feverishly as both sides applied knowledge and experience to the novel situation and Captain Milius met the Bonkoolawal Clan members, the traditional owners of the eastern shore of Western Port. Who was this pale intruder, unschooled in Aboriginal Law, wearing bizarre garments and speaking a strange language? Could these people be mrarts (ghosts) come back to earth, or even their creator hero Lo-an, incarnate? The perception might have been reinforced when the Frenchman traced the path of the sun as he explained the workings of his watch, which could have been interpreted by them to mean that Milius had come from the west, beyond the sunset, from ngamat, where Kulin spirits paused after death before ascending to Tharangalk-bek, the sky country. | The French connection The Baudin expedition was noted for its artwork and the calibre of its scientific studies. These explorers were the first to chart 'Isle des Francais' as an island and it still retains the name 'French Island' in recognition of their exploration. In 2002, to mark the bicentennial of the visit, Dr Francoise Debard, a French veterinarian who had completed a Masters degree on seals studied by the 1802 Expedition, came to Western Port to work with with local people in taking a retrospective look at the Bay over the past 200 years and considering what the next 200 years might bring. Events include a re-enactment at Corinella, wildlife tours on Phillip and French Island, a commemorative seminar on 200 years of change in Western Port and placing plaques and time capsules around the bay. The diary of Theodore Leschenault, botanist on board Le Naturaliste, was translated for the seminar. A bicentennial commemoration is planned of the second French scientific expedition which came to Western Port in 1826. |

Social co-operation, language, music, and an ability to ask “Why?” had seen Aborigines and Europeans independently find their way to Western Port tens of thousands of years apart and had set the stage for another historic reunion, the second within four months, of distant cousins in our modern human family. Wariness and lack of a common language reduced complex communication to chimp-like charades.

Milius noted in his journal that the Western Port people, unlike Aboriginal people they had encountered in Tasmania and Western Australia, had blackened their skin with charcoal and some had a white cross painted on the middle of their forehead and white circles around their eyes. Several had red and white crosses all over their bodies, others had their nasal septum pierced with an ornament of dried straw.

The body ornament suggests the Bonkoolawal were involved in ritual ceremony, perhaps mourning a close relative or receiving messengers from another clan. Like the Europeans, they dressed according to rank and “had with them a big dog which by his skin and his tail resembled a fox, but his head appeared to be large and his muzzle short and gross”.

Pat Macwhirter is author of Harewood, Western Port: Stardust To Us. She supports the establishment of a Bass Coast national park on the eastern side of Western Port and suggests it could be named the Bonkoolawal National Park, after the Bass River Clan.