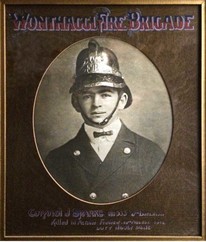

Wonthaggi Fire Brigade member John Sparks, who was killed in action in France

Wonthaggi Fire Brigade member John Sparks, who was killed in action in France WHEN you go into the CFA meeting room at the new fire station on White Road, you will see on the walls an array of portraits of past members going back to the very first days of the Wonthaggi Fire Brigade, which was formed early in 1910 with the sudden establishment of tent town. One picture has been with the brigade since those early days, when an ‘enlargement’ was made by the members to commemorate John Sparks, who, according to the Powlett Express, was “an active member of the Wonthaggi Fire Brigade, one of its [first] members, much respected and a favourite with his colleagues”.

Anyone who has been a member of the brigade over the last 100 years would have looked at the framed and engraved picture of John Sparks over and over again as they entered the station in its different locations. They would have had to acknowledge the robust young man in his brigade uniform and gleaming brass helmet starring down upon them, his expression reminding them of their proud duties and the honour of being an Australian volunteer.

But for so long no one really remembered why his portrait took pride of place at the station, except for the fact that he had been killed in the Great War of 1914-1918. Finally, with the imminent move into the new building and with the centenary of the battle at Gallipoli coming up, the current brigade members decided to do some research. With the help of Sam Gatto and the Historical Society archives, they turned to the local newspapers for information.

John Sparks was mentioned first as a football player, then as one of the young players who had enlisted in 1914, just as the war was beginning. Although he was in the Rifle Club, a precursor to enlisting for many young local fellows, he chose to go to Broadmeadows to enlist. On August 18 1914 the 22-year-old took the oath that he would “well and truly serve our Sovereign Lord, the King, in the Australian Infantry... …and faithfully discharge my duty according to the law”.

There is no further mention of Sparks in our local newspapers until 1916 when the Powlett Express reported, “Official information has been received by Mr John Sparks, Snr, of the death of his nephew, Private John Sparks, who was killed in action in France … he was only 24 years of age and was in the landing and evacuation of Gallipoli and, later, in France. He was held in the highest esteem by his comrades-in-arms in the trenches and around the camp fire.”

The report goes on to describe the customary ceremony that was carried out at the fire station by the members of the brigade where the muffled death-toll was sounded. The article finishes by stating “the Wonthaggi Fire Brigade has the distinction of supplying more volunteers in response to the Empire’s call than any other brigade in Victoria”.

In 1917, when the brigade unveiled their honour roll with the names of all their members who had gone to war, of course John Sparks’ name was among them. At the ceremony the firemen gave “a right-handed salute in honour of their gallant comrades; the memory of John Sparks was further honoured by the whole company standing with bowed heads for a few moments”.

Later it is reported that the members of the rifle club honoured two of their members who had made the supreme sacrifice: J Rhodenight and J. Sparks. After that, not much information could be found on John Sparks, except for the tragic report that his grandfather had died of a broken heart after he had word of John’s death. But, who was his grandfather? Wasn’t John Sparks Snr his uncle? Or perhaps his father?

Finally, in 2015, when the current brigade put the word out that they were looking for relatives of John Sparks, they found that the Morelys still lived in Wonthaggi and that members from the other side of the family lived in Drouin. The whole group came together one Sunday morning at the station and presented Sparks’ medals to the brigade: the Victory Medal, the Star Medal and the British War Medal plus the “Dead Man’s Penny”, a macabre offering given to the families of anyone killed in the war. These had been presented after the war to Sparks’ aunt, Mrs Frances Wardle, of South Dudley, whom the War Office deemed next of kin.

When he signed up, Sparks had little idea that he was headed for Gallipoli and, surviving that, for the north-east front along the German border in France after a short stint in hospital with an injured foot and then a pleasant rest and recreation leave in England where he met a young English woman, fell in love, and left her with child. He knew what he had done, and tried to have his enlistment transferred to the English Army so he could return to his love and his child when the war was over, but to no avail. He was shipped out along with his Australian comrades and died in a small town named Albert in the province of Pozières without ever knowing he had a son. His family back in Australia had no knowledge of the son either.

In fact, the full story only came out when the War Office tried to find out exactly who John Sparks’ relatives were so they would know who to give the medals to and who should receive the “widow’s” pension now that he was gone.

It turned out there was a fair bit of dispute over who was next of kin and who could claim Sparks’ effects, his medals and citations and the pension. In 1921, Warrant Officer R E Trewern in Dandenong documented the situation after he had made enquiries in Wonthaggi from various residents and solicitors to find the facts of the matter.

Sparks was born out of wedlock, but he was not aware of this when he enlisted. He thought his grandfather was his father and his aunts were his sisters. The aunts were “working women” and kept the home together until Sparks could earn his own living. The grandfather was a pensioned miner and respected union man. As we know from the local papers, he died upon hearing of his grandson’s death in 1916. It was the youngest aunt, Frances, who essentially brought Sparks up and was later deemed by the warrant officer to be morally most entitled to her nephew’s effects.

Sparks’ real mother had left the family home on Baillieu Street after giving birth, never to return. She married William Lamb, a relatively well-to-do farmer from Dollar near Stony Creek and bore him two children. The mother died early and so had no claim, but Mr Lamb made a claim on behalf of his two offspring since they were the birth mother’s children although they had never met their half brother, who did not know of their existence. No moral entitlement there.

So Frances Wardle of South Dudley received the medals and effects of John Sparks, deceased. Shortly thereafter, the war office received a one sentence note from Mrs Wardle saying the medals had been stolen from her house, although nothing else had been touched. The War Office replied that they could replace the stolen medals, but she would have to pay for them. Astonishingly, whoever took them decided to give them back by throwing them through the window. The Wonthaggi Fire Brigade now has them.

About the time Mr Lamb was arguing his children’s case for the war pension, another claimant turned up. Here is A. Reailly’s report made August 1920 to the Officer in Charge at Australia House, London, who had asked for discreet enquiries: “I beg to report having made enquiries at No. 20 Old Gloucester Street, W.C.1, London where I saw Miss Lucy Lockett, who produced her son John William Lockett, age 3½ years, the illegitimate child of Corporal J. Sparks for whom she receives a pension.”

It seems young John William Lockett was certainly morally entitled to Sparks’ pension. His mother generously made no claim on the medals in Mrs Wardle’s possession.

Members of the Fire Brigade intend to go to France in 2018 to, at last, make a formal pass over Corporal Spark’s grave in Albert. His family will also attempt to connect, at last, with the Lockett family at the same time.

This essay was first published in The Plod, the newsletter of the Wonthaggi Historical Society.