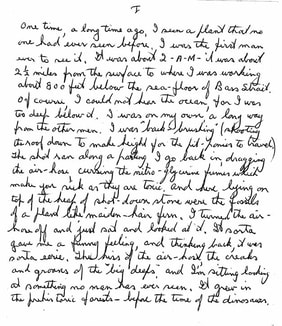

Plant fossil, by Arthur Baker, date unknown. In the collection of the Wonthaggi & District Historical Society

Plant fossil, by Arthur Baker, date unknown. In the collection of the Wonthaggi & District Historical Society Carol Cox, who is transcribing the stories, said they were passed to the historical society by Peter and Lorna Hall. In the 1980s they were lessees of a caravan park in East Gippsland where Arthur lived in an old small caravan, and he entertained them for many hours with his stories which he eventually put into writing for them.

Mr and Mrs Hall knew Arthur as a retired wild dog trapper who had a vast knowledge of the East Gippsland Highlands, possibly because his father had been a botanist. Judging from his notes, he was also a miner at some stage.

Arthur is buried in the Marlo cemetery - Mr Hall believes he died in the late 1980s aged in his late 70s.

By Arthur Baker

One time, a long time ago, I seen a plant that no one had ever seen before, I was the first man ever to see it. It was about 2 a.m. It was about 2½ miles from the surface to where I was working about 800 feet below the sea-floor of Bass Strait. Of course, I could not hear the ocean, for I was too deep below it.

I was on my own, a long way from the other men. I was “back brushing” (shooting the roof down to make height for the pit-ponies to travel). The shot ran along a parting, I go back in, dragging the air-hose, cursing the nitro-glycerine fumes which make you sick as they are toxic, and here lying on top of the heap of shot-down stone were the fossils of a plant like maiden-hair fern. I turned the air-hose off and just sat and looked at it. It sorta gave me a funny feeling, and thinking back, it was sorta eerie. The hiss of the air-hose, the creaks and groans of the “big deeps” and I'm sitting looking at something no man has ever seen.

It grew in the prehistoric forests – before the time of the dinosaur. It belonged to the Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous age, 350 – 400 million years old. When I knocked off I took some of the slabs “out-bye” (upstairs) with me. The mine kept some, and some went to the Geological Museum, Mines Dept, Melbourne, and I took some home, cut it into small slabs with a hack-saw (hard stone) and painted it with clear varnish to stop the air from destroying it. Most I gave away to the women and kids, and some to the local schools, and some I kept, as ornaments. I forget what its geological name was.

That was the oldest plant I have ever seen – and that night, I was the first and only man to have ever seen it.

I also got paid for the dog-watch shift – 6 shillings a day.

12 hours a day, start at midnight, 7 days a week, 6 shillings a day, that's 42 shillings a week (42/- = 2 pounds, 2 shillings) for 84 hours per week.

That was long ago – in the good old days !

“Magnart”

“Magnart”, German, she was quite big. I think she was a barque. She came ashore at Venus Bay, at Tarwin Meadows. The skipper had been in some sort of trouble on another voyage, and had to put some of his own money in, to get the job of the Magnart's captain.

She came out from Germany to Melbourne, but somehow missed out on a cargo at Melbourne, so she headed for Sydney. She was low in ballast and as she came around Cape Patterson she had trouble keeping her rudder deep enough to steer properly. The inshore current caught her and she stranded on the beach in heavy surf.

August Sorenson, an old Danish seaman I worked with in the mines, told me of this. Murray Black owned Tarwin Meadows Station, his farm-hands had a bank & school there, so it was a small town they all lived in. He told me nobody knew she was ashore, till next morning, when 2 of his musterers seen the big masts sticking up above the sand hills. When they rode over there, all the German seamen were in a fort they had built on the beach, from boxes and barrels. They were heavily armed for they had heard stories of the Australian blacks.

They stayed there living on the beach for a long time. It appears no attempt was made at salvage by the German company who owned the ship, and she began to break up. The story goes that barrels of brandy drifted down into Anderson's Inlet (Inverloch) and up the Tarwin River and were found by some of the Magnart's men. They would go over to the river and get drunk – and lost on the way back to the camp on the beach, so they pulled a mast out of the ship and stood it on the highest sand hill, with a ship's lantern hanging from it. I can show you this sand hill, and they say, that was the beginning of a licence for the Lower Tarwin pub.

Eventually Murray Black bought the ship. He had teams of working bullocks, so he and his men pulled her to pieces. Today the figurehead (a white lady) stands in the old homestead garden and staircases and ship's fittings/furniture are built into the old house.

As I told you, when children we would swim the channel that had formed on her landward side and climb up on to her, look down in the holds, half-full of water and a bit frightening too, then my father really frightened us with the story of the big octopus that lived in this wreck – and finish Magnart, no more visits to her! Of course, the old man's idea was to keep us out of the heavy surf, bad undertow there, but we were like little fishes, and it didn't frighten us that much, but by crikey, the old man's story did.

In later years I used to go there a lot at night after big gummies, as a big wash hole had formed there. She gradually got buried in the sand, but I know where she is. They say, in time, they got the seamen back home to Germany. I hope they did.

I don't know the date of her stranding, but it should be in the book, “Shipwrecks of the Gippsland Coast”.

Thanks to Carol Cox for alerting the Post to Arthur Baker’s distinctive stories. Carol, who is transcribing the stories, notes that the historical society is unable to verify the facts Arthur describes.