There was nothing in Agnes Doig’s middle class family background to indicate that she would become a champion of the poor and downtrodden and a legend of Wonthaggi. Photo: Melbourne University collection

There was nothing in Agnes Doig’s middle class family background to indicate that she would become a champion of the poor and downtrodden and a legend of Wonthaggi. Photo: Melbourne University collection WHEN you look at a picture of Agnes Doig from the Melbourne University Archive, she looks like your next-door neighbour – bright, energetic, kind – but take another look and you can see something else, something strong and clear-eyed.

“I had a storm in me,” she said when describing herself as a speaker at political meetings in Korumburra at first, then Wonthaggi, Melbourne, Sydney, Canberra. The storm was caused by a strong sense of social justice that drove her to political activism. Although she came to it late, she defined herself as a true believer, a Communist through and through.

“Strangely enough,” she said, “I had a middle class, religious background.”

She was born Agnes Smith, in 1908 in Shotts, Scotland, a coal mining town of about 40,000. Her father was a mining contractor, which meant he was in charge of the construction and maintenance of the colliery.

| His job was to keep the mine plant working so the miners could extract as much coal as possible without delay. He was directly answerable to the owners, who usually had little contact with the miners unless there was trouble. It was an important position and well-provided for, but fraught with anxiety, which Mr Smith kept hidden from his family as much as possible. | This essay was first published in The Plod, the newsletter of the Wonthaggi Historical Society. |

It was when a young man named Walter Doig came to work for her father that Agnes’s world made a dramatic shift. Walter, or Wattie, as everyone except Agnes called him, was a working man, well-read, articulate and extremely opinionated. 1926 was a year of strikes and strife in Scotland. The unions were fighting over wages, and the owners pushed the government to crush them. Wattie’s radical ideas about social justice, unions and conditions in the mines of Scotland opened Agnes’s mind to a world from which she had been protected. Coal mining was always dangerous and the fight between miners and the bosses in Scotland was ongoing. Wattie was especially concerned about the police bashing of the unionists. As he explained his ideas and the political situation in the mines to a receptive Agnes, she fell in love with him. They became engaged.

Wattie had joined the fray by becoming active in the Communist Party and was thus on the edge of real trouble such that the union offered him a ticket to Canada to avoid his being arrested. He decided, in spite of, or because of, his engagement to Agnes, that he had to leave Scotland to save himself and to find a better life. The plan was that he must accept the offer of passage to Canada where Agnes would meet him when he was established. However, when he got to the docks in Liverpool, there was no room on the Canadian ship. Wattie was given a ticket to Australia instead. The year was 1927.

One can only imagine the conversations that went on between 19-year-old Agnes and her parents when she informed them that she would follow Wattie to the ends of the earth. That she actually did so, on her own, in 1928 is strong indication of her independence and determination.

She met Wattie in Melbourne where they spent a year, then came to Wonthaggi where their only son, also Walter but called Terry, was born in 1929, the beginning of the Great Depression.

In 1932, Wattie took his young family to Korumburra where he got work in the small, private coal mine called Sunbeam Colliery. They found a coal industry with few regulations and minimum pay. There was barely enough air underground for the men to breathe and they were only paid for the amount of coal they produced. In a bad week with a cave-in, for example, that could amount to little or nothing.[1]

When Wattie began talking to the men about their terrible conditions and poor wages and told them what the power of organised action could do to change that, they made him the union president. As president, he organised representations to the Wages Board to set an award of 14/- per day. The mine owner refused to pay, so a period of strife ensued, that would end in the first “Stay-down Strike” in Australia in 1937.

Meanwhile, Agnes was becoming an active organiser herself. She said she was moved by the suffering of the miners’ families who were trying to make do on so little. She thought she could convince the Presbyterian Minister to help her create an organisation that would allow the miners’ wives to help themselves, but the minister was antagonistic toward anyone in a union movement. Agnes had a row with him and walked out of the church for ever. “I turned towards those who gave concrete help rather than those who gave lip service to us,” she said. “I became a teacher in the Salvation Army. I also turned to Wonthaggi because of the example set by the Wonthaggi Miners Women’s Auxiliary.”

The WMWA was started in 1934 as part of the Broad Committee the Union had established to get the workers through the ’34-’35 Strike, one of the longest stop-work events in the mine history. As part of the Broad Committee, the women focussed on assisting the miner’s wives to keep home and family intact. Over time it widened its focus to schools, hospital, mothers’ club, library, comfort station… and much more. Its members included nurses and trade unionists, mothers’ clubs volunteers and schoolteachers.

Agnes said, “I went to Wonthaggi to find out what they did and told them I needed help in starting a Women’s Auxiliary in Korumburra. I told them there was a lot of hardship among miners’ wives and children in Korumburra and I knew that women could raise funds in a way that the miners couldn’t. After discussion with the Wonthaggi Women, they sent over Kath Oakley, who was the secretary of the group. She and I went around to the women – miners’ wives to start with – throughout the town and recruited them for the Korumburra Women’s Auxiliary. We had a very good response from the women. Twenty joined almost immediately.”

Agnes also travelled to Melbourne speaking at universities and mothers’ clubs to elicit help as well as raising funds and distributing food, clothing, milk and fruit to the families.

“We found a place for the miners’ children and it was large enough for the rest of us as well. We raised money for fruit and milk for the children and for pregnant women. And we went from there. We ran fortnightly meetings. We had public meetings at the Mechanics Institute and at the Picture House and we had women’s meetings and some of us would present papers and read them out and the rest would respond and then we would set a target for what we would do. The topics were mainly around the women’s problems and also about fighting for better conditions. We did things like adopting a child from Spain during their civil war. The Auxiliary had picnics and entertainment and carried on for four-or-five years raising money. We women got to understand the fight the men were having over wages and conditions. Every woman in Korumburra, whether in the union or not, stood behind their men in their fight for better conditions.

“The Korumburra Women’s Auxiliary left a good mark on Korumburra at the time. Wherever we saw hardship we visited people. We do good work whether those in need were miners or not.”

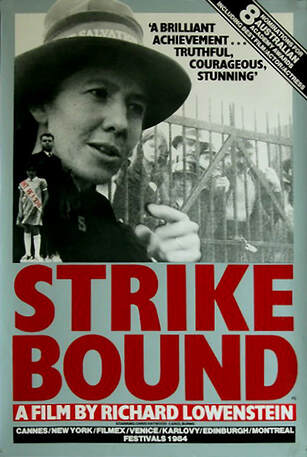

Richard Lowenstein’s 1984 film Strikebound was

Richard Lowenstein’s 1984 film Strikebound was based on the story of Agnes and Wattie Doig.

“Walter and I talked mostly about politics,” said Agnes. “We used to discuss conditions and all the ways we would beat the boss.”

The union, led by Wattie, was getting nowhere with the bosses, who regularly tried putting in scab labour on the sly: “When they introduced scab labour, the women played a big part,” said Agnes. “We had demonstrations down to the mine against the scab labour. There was one man (scab) who kept the whole mine running when the managers laid the men off, and the women decided they’d had enough of him. The police came with them, too, and they got him out of there. It wasn’t always easy. I was put in gaol three times in relation to this struggle.”

While Agnes was busy organising the women, Wattie was meanwhile organising the radical strike action the men at Sunbeam would take if the bosses continued their delaying tactics and refused to bargain for improved conditions and wages. He discussed his plans for action with the Miners Federation members in Wonthaggi, told them he was going to lead a ‘stay-down’ strike in September 1937 in an act of defiance and stay down there until the mine managers changed their minds. The Wonthaggi Branch of the Union vowed to support him. The Wonthaggi Women’s Auxiliary also joined the Korumburra Women in support and would bring goods and money with them.

In preparation for the strike, Agnes went to the secretary of the Korumburra Chamber of Commerce to ask for help. “I asked him if he would supply food without broadcasting it, and he agreed to supply food and medicine to the men to aid the strike. He was quite pleased to get the £20 we offered him. I think that came from Wonthaggi, if I remember,” said Agnes. “The Communist Party also sent up truckloads of food, clothing and things like that.”

On the day planned for the ‘Stay-down” action, the management tried to lock the miners out of the mine, but they managed to break in and go down into the mine to stay. Three days later, while the men were refusing to budge, the news of the strike was relayed to Wonthaggi, as planned, and an on-the-spot stop-work meeting was called at the State Mine where all agreed to adjourn and march en masse to the aid of the Sunbeam Strikers.

Waiting buses took the demonstrators to the outskirts of Korumburra. From there, 350 miners and their wives and supporters, from Wonthaggi and Korumburra, led by the Wonthaggi Union Band, followed by both the Korumburra Women’s Auxiliary and the Wonthaggi Women’s Auxiliary marched two and a half miles through the town to the Sunbeam pit head. At the same time two of the buses from Wonthaggi diverted to Jumbunna, “where non-union labour had been hired to break a nine-week strike for Union recognition and improved wages. Despite being menaced by armed men, Committeemen, Bill Stirton and Bob Hamilton and their crew, induced all the non-unionists to stop work; 9 September 1937 proved to be a day of massive and popularly supported action.”[2]

When the marchers got to the coal mine, the men began to come up, partly because one of them was very sick, but also because word had been sent down that the managers had given in and the conditions would be met. “We had a big meeting in the Picture Theatre after that!” said Agnes.

One can imagine Wattie and Agnes talking the whole thing over through that night. Their excitement at a goal achieved would have dominated their talk, but their plans for the future would have taken over. They knew that the strike would have big repercussions for the future. “Of course!” Wattie was absolute about the Communist Party leading the way. Very soon, Agnes, too, would be ready to give up on the Salvos as she had the Presbyterians and declare herself a true believer.

“I joined the Wonthaggi Chapter of the Communist Party in the late thirties,” she said, “although I was very sympathetic before that. It was when they sent those truckloads of goods to the miners underground that my ideas became firm.”

Agnes, continued to work with the Korumburra Women’s Auxiliary for three years after the stay-down strike, but the colliery was closing down by then. Sunbeam Mines didn’t completely fold until 1959, but by 1940, it was time for Wattie, Agnes and Terry to move on. They moved into a miner’s cottage in South Dudley.

“As soon as we were settled, I joined the WMWA,” Agnes said. “Agnes Chambers was President when I became Secretary. She and I did some excellent work together. I had a high regard for her. She did some wonderful work. Being a mining town, it was much easier for us to work than being in a country town like Korumburra where so many of the farmers were against the miners’ unions.”

Agnes knew that in Wonthaggi the Women’s Auxiliary commanded great respect. They were invited to all the events. There were many women who were in both the mothers’ club and WMWA. They did outstanding work. The Australasian Group Society was sponsored by WMWA and they raised the funds to send Noel Counihan (an Australian social realist painter and printmaker who spent some time in Wonthaggi) overseas and they helped a dancing group. Anything that was progressive at all was supported by the Women.

At election time, they gave £20 to Labor Party and £20 to the Communist Party. The women in the Auxiliary were politically aware. Agnes remembered one woman, “A Catholic woman who came along to one meeting, but then she kept coming for maybe six or seven meetings. When she finally had the courage to stand up, she said she had come to the meetings to spy, but when she saw the kind of work we did and the dedication we had for social justice and when she learned about the things we believed in she said, ‘I am only too proud to remain a member.’

“It was a very progressive auxiliary. Anyone who was in sympathy with the ideas of the miners’ union was welcomed into the group. The women were with their men.”

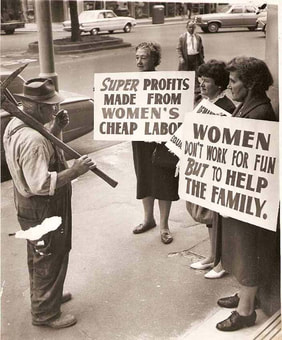

Taking the message to Melbourne: Agnes Doig, centre,

Taking the message to Melbourne: Agnes Doig, centre, on the steps of the Victorian Parliament, 1960s

“I’ve always been nervous about speaking,” she said, “but once I got going it was like there was a storm in me. I was on the Communist Party Senate team, and one year we all went to the Declaration of the Poll. The comrade who was going to speak for the Communists got asthma very badly, so they asked me to speak. He told me it wouldn’t be a trial because there would only be a few people there.

“Well, that was the year Frank McManus (DLP) got back into the Senate and the whole hall was full of people. There were policemen at the back and all the Labor people were there and the Country Party. And a whole bunch of Catholic women turned up to support McManus. And the whole crowd carried on with hooting and shouting and booing and campaigning. TV’s news cameras were there.

“However, when I, the speaker for the Communist Party, got up to speak, they turned the cameras off. Well, what could I do but carry on? And that’s what I did. I carried on and what was supposed to be a five-minute speech turned into three-quarters of an hour. No one doubted my ability to carry a crowd after that.”

Agnes Doig declared that she never regretted meeting Walter Doig and following him to Australia.

What a life!

References

[1] Karen Kissane, “The Man who Led The Miner’s Strike,” The National Times, 8 November 1984. P 10

[2] Reeves, Andrew, Up from the Underworld. Pp 89-90