Unless specified, all quotes come from Wonthaggi and District Post-War Reconstruction Plan written by Wonthaggi District Trades and Labor Council, published as WWII ended.

Unless specified, all quotes come from Wonthaggi and District Post-War Reconstruction Plan written by Wonthaggi District Trades and Labor Council, published as WWII ended. THE years between the wars – 1919 to 1939 – were hard years for the working man in Australia. After the First World War, the British Government sent Otto Niemeyer, a London banker, to tell Australia how to get out of debt. His advice was to slash government funding and wages by 30 per cent.

“The State Coal Mine began sacking many miners and cut wages,” Lyn Chambers wrote in a history of the Wonthaggi Miner’s Union Women’s Auxiliary. “It wasn’t long before they stopped improving safety in spite of thirteen miners being killed between 1930 and 1933. The Union called a strike in 1934 that lasted for five months.”

During that time, the miners and the community rallied together to keep their families’ heads above water. They created a committee that oversaw sub-committees for Relief (wood, clothing, food, fuel), Propaganda (speakers to explain conditions and raise funds), Entertainment (raising funds for food and alleviating stress), and Distribution (sharing food to each according to family size).

When World War II erupted, the people of Wonthaggi were used to volunteering, to hard work, to creating a united front in the face of adversity. They were ready to do their bit. Local groups – the men serving the cause in the mine as well as at the front, the women working with churches, MUWA, CWA and Mother’s Club making knapsacks, organising air-raid shelters and ambulance boxes, and, of course, the Air Observers group – kept the community going. All the groups worked together to get a maternity wing for the hospital, which was opened in 1944.

In the post-war era, the people of Wonthaggi felt that no section of the community had been more loyal than them in “Providing the coal to fire the furnaces of the Army of Freedom; the coal without which there could be no guns, tanks, planes, or shells, the coal that must be dug from the depths of the earth by sweat and skill and courage”.

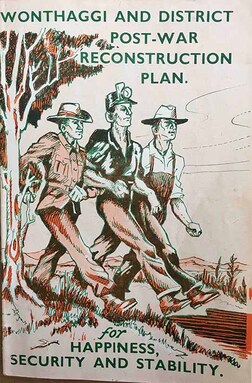

Determined to ensure happiness, security and stability in the post-war period, a reconstruction committee was formed with representatives from first and foremost the Miner’s Union and the Miners’ Union Women’s Auxiliary.

These were joined by the Amalgamated Engineering Union, Federated Engine Drivers and Firemen’s Union, Deputies’ Union, Shop Assistant’s Union, Teachers’ Union, Clothing Trades Union, Liquor Trades Union, hospital Employees’ Union and Miners’ Union, Wonthaggi Hospital Committee and Hospital Employees’ Union. Inverloch Citizens, Kilcunda Citizens and the San Remo Citizens and Fishermen’s Club could not be left out. And certainly the Wonthaggi branches of the ALP, Communist Party, and Eureka Youth Club, were included.

Together, these groups expressed their dreams for the future of the Wonthaggi District. They wanted to make a new world with equal opportunity for all; to ensure success for every citizen whether worker, farmer or small businessman. They declared that their program of reconstruction was not “a means to an end in itself, but evidence of a progressive movement in the interest of the people of the district”. They would be a broad body of representatives throughout the community and work together to make a new world of happiness, security and stability. It was an honourable dream.

The plan of the people

The idea, which was in the planning well before the War actually ended, began with coal, “the life blood of the District, an asset that must be preserved, expanded and exploited in the interest of the State as a whole, and worked in the public interest”, which meant that mine workers must be given representation in the administration of the industry.

They should begin by ascertaining the total black coal resources in the area of Jumbunna, Inverloch, Wonthaggi, Dalyston, Kilcunda and Bass Valley to Nyora and expand the rail services where necessary so all coal resources could be unified and accessible.

To this end, they had a dream of creating railway construction workshops. The central yard at the State Coal Mine with its existing network of railway lines and available space was considered ideally situated for creating a railway industry where locomotives, passenger cars, wagons and trucks and all railway requisites could be manufactured.

“This would provide an outlet for all apprentices upon becoming tradesmen, thus avoiding their need to leave the district in search of work. It would also provide for a flow of two-way rail traffic which would avoid waste and cheapen the cost of transport.”

They thought the existing power house could be up-dated and used in firing the furnaces of the workshop. They thought that what they had learned during the war effort about industrialisation and manufacturing could be put to use in establishing “a factory for the production of ball-bearings and other similar products.”

To that end they pointed out that bauxite deposits existing in Gippsland with close proximity to Wonthaggi could warrant the establishment of a new aluminium industry in the locality. They had a dream of expanding the already established White Manufacturing Company for production of clothing and employment of female labour, which would help with family stability and stop any population drift to the city.

They dreamt of establishing a local canning and dehydration plant to create economic stability for the large pastoral district, “with potentialities of vast expansion to meet requirements of internal and export trade…and elimination of all commission agents’ fees and freight.”

Their ideas expanded to creating farm co-operatives with shared use of machinery, co-operative marketing and even creating a municipal market along the lines of the major markets in the city.

Of course, all this would require educational improvements so that “Australia remains a vital link in the chain of world unity.” They supported the Australian Council of Trades Unions Educational Programmme and dreamt of all students “receiving their rights in elementary, vocational, literary, musical and artistic education.”

They listed 15 steps to that aim, including a calling on the Government to act as a co-ordinating and liberalising authority to establish free education for all, extension of facilities, free medical and dental services for students, reduction of class sizes, raising school leaving age to 16 years and revising teacher training.

They called for new school buildings, and many municipal improvements including higher standard of housing, sewerage, comfort station, public library, parks and playgrounds, swimming pool, bus service, youth cultural centre …

Many of the ideas came to fruition but, as the need for Wonthaggi’s coal waned, the dream of becoming a substantial mining, manufacturing, and industrial centre began to fade.

Although the mine eventually closed in 1968, the town did not die. Wonthaggi remains the municipal centre of the shire, and many of the dreams have been fulfilled: the new secondary school is almost finished, the leisure centre is in constant use, the streets are busy with shoppers who come from near and far, the Union Theatre is still the cultural

centre of the town.

Many of the original families, who came from around the world to mine the coal, never left the town; their off-spring are still here, still honouring the idea of it as a place of equal opportunity. The Wonthaggi Historical Society helps to maintain the memory of the dreams of the people who made this place, through recorded memories, photographs and archival documents like the Post War Reconstruction Plan.

This essay was first published in The Plod, the newsletter of the Wonthaggi & District Historical Society.