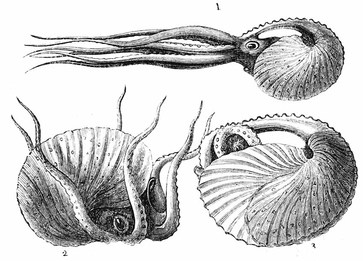

Illustration of paper nautilus" (Argonauta) by Philip Henry Gosse, from Natural History: Mollusca (1854)

Illustration of paper nautilus" (Argonauta) by Philip Henry Gosse, from Natural History: Mollusca (1854) By Mark Robertson

BACK in the olden days (the `60s and `70s), the centrepiece of many homes was the china cabinet, a glass-fronted tomb containing all the special and delicate treasures one accumulated and displayed: Royal Doulton figurines, special teacups and saucers, curios from the P&O cruise to the far east, and those strange silver-plated cake tongs, the least-used device ever invented.

BACK in the olden days (the `60s and `70s), the centrepiece of many homes was the china cabinet, a glass-fronted tomb containing all the special and delicate treasures one accumulated and displayed: Royal Doulton figurines, special teacups and saucers, curios from the P&O cruise to the far east, and those strange silver-plated cake tongs, the least-used device ever invented.

One resident of these "arks of the useless" always caught my eye – pure white globes, made of the thinnest, most translucent material, all identical, but all slightly different. Their other common habitat was on top of the lounge room pelmet, lined up from smallest to largest, but they were always less luminous there, covered in a layer of dust (coal dust if you lived in Wonthaggi).

I found out that this treasure was called the paper nautilus, and it was to be one of the catalysts for my ongoing obsession with our incredible local marine world.

The paper nautilus is produced by a small pelagic octopus (Genus Argonauta), which uses two of its tentacles to secrete a calcium substance, somehow forming two halves of a chamber in which it deposits its eggs, settling at the mouth to protect them. It often also shelters the much smaller male.

Illustration of paper nautilus" (Argonauta) by Philip Henry Gosse, from Natural History: Mollusca (1854)

Talk about maternal overprotection! These small cephalopods don't seek out a cavity on the sea floor to house their young – they construct their own, producing a home which far surpasses, in delicacy and beauty, the finest porcelain the cleverest human artist/engineer could imagine, let alone produce. Looking at such clever design only reinforces the reality that man is not the pinnacle of life.

After serving their purpose of sheltering the new offspring, certain tidal and weather conditions may lead to the shells being washed up along our beaches in large numbers. If you are attuned to these natural cycles, you may be lucky enough to find some. Flat Rocks and Venus Bay seem to attract them.

I have only ever found one – a pathetically small specimen, seven centimetres in diameter, nestled among the seagrass and mud on the Newhaven boat ramp. Nowhere near as impressive as the 20-centimetre giants I saw in many china cabinets. How it was not crushed under a boat trailer tyre, or a careless boot, I will never know.

When the paper nautiluses (or nautili) reach the shore, many still contain the remains of the parents. Pacific gulls are ready to pounce upon this delicacy, leading to many shells being damaged by vicious beaks, making undamaged shells a truly rare find.

Shells are one of the true treasures found by hardy beachcombers. The shell museum at the Inverloch environment centre displays many fine specimens. Each time I study a shell I marvel at the complexity and sheer skill of our neighbouring marine species.

We need to do all we can to protect and celebrate their home. In the modern world, increasing acidification of seawater from our ceaseless burning of fossil fuels may soon render such incredible shell-forming impossible. The acidic environment will dissolve calcium shells, rendering many species extinct. Too bad if your food chain relies upon krill or other molluscs – goodbye to the whales! It would be a tragedy if our grandchildren could not experience the delight of finding a fresh, beach-washed shell. They may have to make do with plastic instead.

I found out that this treasure was called the paper nautilus, and it was to be one of the catalysts for my ongoing obsession with our incredible local marine world.

The paper nautilus is produced by a small pelagic octopus (Genus Argonauta), which uses two of its tentacles to secrete a calcium substance, somehow forming two halves of a chamber in which it deposits its eggs, settling at the mouth to protect them. It often also shelters the much smaller male.

Illustration of paper nautilus" (Argonauta) by Philip Henry Gosse, from Natural History: Mollusca (1854)

Talk about maternal overprotection! These small cephalopods don't seek out a cavity on the sea floor to house their young – they construct their own, producing a home which far surpasses, in delicacy and beauty, the finest porcelain the cleverest human artist/engineer could imagine, let alone produce. Looking at such clever design only reinforces the reality that man is not the pinnacle of life.

After serving their purpose of sheltering the new offspring, certain tidal and weather conditions may lead to the shells being washed up along our beaches in large numbers. If you are attuned to these natural cycles, you may be lucky enough to find some. Flat Rocks and Venus Bay seem to attract them.

I have only ever found one – a pathetically small specimen, seven centimetres in diameter, nestled among the seagrass and mud on the Newhaven boat ramp. Nowhere near as impressive as the 20-centimetre giants I saw in many china cabinets. How it was not crushed under a boat trailer tyre, or a careless boot, I will never know.

When the paper nautiluses (or nautili) reach the shore, many still contain the remains of the parents. Pacific gulls are ready to pounce upon this delicacy, leading to many shells being damaged by vicious beaks, making undamaged shells a truly rare find.

Shells are one of the true treasures found by hardy beachcombers. The shell museum at the Inverloch environment centre displays many fine specimens. Each time I study a shell I marvel at the complexity and sheer skill of our neighbouring marine species.

We need to do all we can to protect and celebrate their home. In the modern world, increasing acidification of seawater from our ceaseless burning of fossil fuels may soon render such incredible shell-forming impossible. The acidic environment will dissolve calcium shells, rendering many species extinct. Too bad if your food chain relies upon krill or other molluscs – goodbye to the whales! It would be a tragedy if our grandchildren could not experience the delight of finding a fresh, beach-washed shell. They may have to make do with plastic instead.