By Meryl Brown Tobin

LAST spring hundreds of magnificent creamy-white flower spikes shot up out of grass skirts at the Grantville Nature Conservation Reserve (GNCR) and the adjoining sand and gravel reserve.

Nature-lovers were rapt to see this botanical phenomenon, which followed the February 2019 bushfires. On seeing a photo of Grantville’s grass tree forest, Dr Mary Cole, an honorary senior fellow at the University of Melbourne, wrote: “This is a wonderful picture because it shows healthy grass trees … There are few areas with such healthy grass trees around.”

LAST spring hundreds of magnificent creamy-white flower spikes shot up out of grass skirts at the Grantville Nature Conservation Reserve (GNCR) and the adjoining sand and gravel reserve.

Nature-lovers were rapt to see this botanical phenomenon, which followed the February 2019 bushfires. On seeing a photo of Grantville’s grass tree forest, Dr Mary Cole, an honorary senior fellow at the University of Melbourne, wrote: “This is a wonderful picture because it shows healthy grass trees … There are few areas with such healthy grass trees around.”

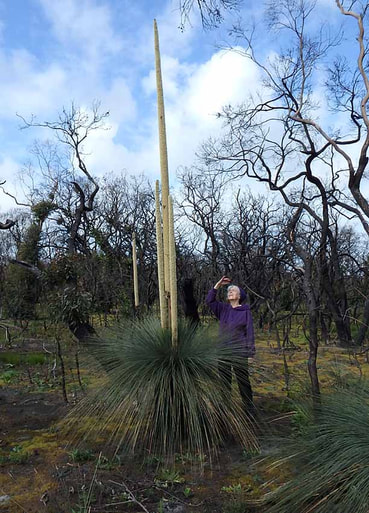

The author is dwarfed by the flower spike on a Grantville grass tree regenerating after the February 2019 fire. Photo: Hartley Tobin

The author is dwarfed by the flower spike on a Grantville grass tree regenerating after the February 2019 fire. Photo: Hartley Tobin Many wanted an assurance that the grass tree forest was protected but no one seemed to know. Their status depended on who owned or managed the land on which the forest was situated – the land covered by a sand mine company’s work authority, the buffer zone surrounding it or the conservation reserve.

As the GNCR is an undeveloped reserve with no formal tracks and almost no signage, it was hard to find out. No one seemed to have mapped the exact position of the forest; indeed, few were aware that one of the best sites for grass trees in Victoria, indeed Australia, existed in Grantville.

Finally, Robbie Viglietti, a director and quarry manager of Sand Supplies Pty Ltd, the company that runs the sand mine, provided the information. With the help of satellite photos/maps, he confirmed that most of the grass tree forest is situated on the excavation site, meaning there is virtually no protection.

Most of the remainder is on the mine’s buffer zone and so part of the conservation reserve. It is protected but it is closed to the public for the life of the sand mine. Fences, gates and signs have now been erected to keep people out.

So the protection status of the grass tree forest is far worse than suspected.

As the GNCR is an undeveloped reserve with no formal tracks and almost no signage, it was hard to find out. No one seemed to have mapped the exact position of the forest; indeed, few were aware that one of the best sites for grass trees in Victoria, indeed Australia, existed in Grantville.

Finally, Robbie Viglietti, a director and quarry manager of Sand Supplies Pty Ltd, the company that runs the sand mine, provided the information. With the help of satellite photos/maps, he confirmed that most of the grass tree forest is situated on the excavation site, meaning there is virtually no protection.

Most of the remainder is on the mine’s buffer zone and so part of the conservation reserve. It is protected but it is closed to the public for the life of the sand mine. Fences, gates and signs have now been erected to keep people out.

So the protection status of the grass tree forest is far worse than suspected.

*****

To understand how we got to this point we have to go back in history.

The 400-hectare Grantville reserve complex, made up of the Grantville Tip, the extractive site and the conservation reserve, was reserved in 1921 to protect its sand and gravel resource. As Robbie Viglietti points out, the reserve only exists at all today because of the sand.

In the late 1940s and ’50s extraction started at the Shire of Bass pit (now the Grantville Tip), at a Country Road Boards (CRB) pit next to it, and at The Gurdies. When the old shire pit ceased extraction, it became landfill by default – the Grantville Tip.

In the late 1980s Robbie Viglietti’s company applied to revive extraction at the CRB pit south of the tip. It was not until 2001 that they finally received a works authority. Much of the intervening 14 years had been taken up with compiling reports for Bass Coast Shire Council on the site’s flora and fauna, indigenous cultural heritage, groundwater and other environmental issues.

These included a 1994 Biosis report on the fauna of the gravel reserve by AS Kutt and JY Yugovic. They wrote that the Grantville gravel reserve and the adjoining conservation reserve "represent the southernmost remnant of native vegetation in a chain of partially connected remnants which collectively comprise most of the remaining native vegetation in West Gippsland, an area which is over 95 per cent cleared.

“Sand mining, residential development and land management are important issues affecting the future maintenance of these connections. Given these conflicting land-use pressures, gazetting this reserve should be a priority for regional conservation authorities.”

They concluded, "All vegetation communities [at the reserve] are considered to be of state (Grassy Woodland, Swamp Scrub) or regional (Dry Heathy Woodland, Dry Forest, Riparian Forest, Wet Heathy Woodland, Wet Scrub) conservation significance" (p58).

And they recommended that "consideration be given to transferring the south-eastern section of the gravel reserve, which includes the creek environment, to the adjacent nature reserve. This highly significant 17.5.ha area supports five vegetation communities, including Riparian Forest and Grassy Woodland".

In 1996 a regional sand extraction strategy adopted the recommendation and addressed the need to maintain vegetation linkages between the Grantville nature reserve/gravel reserve and areas of native vegetation further north, to facilitate wildlife movement and enhance reserve viability.

The strategy also listed significant flora, such as the green-lined greenhood and cobra greenhood, and fauna, such as the giant Gippsland earthworm and orange-bellied parrot and swift parrot, in the Grantville gravel reserve.

The 400-hectare Grantville reserve complex, made up of the Grantville Tip, the extractive site and the conservation reserve, was reserved in 1921 to protect its sand and gravel resource. As Robbie Viglietti points out, the reserve only exists at all today because of the sand.

In the late 1940s and ’50s extraction started at the Shire of Bass pit (now the Grantville Tip), at a Country Road Boards (CRB) pit next to it, and at The Gurdies. When the old shire pit ceased extraction, it became landfill by default – the Grantville Tip.

In the late 1980s Robbie Viglietti’s company applied to revive extraction at the CRB pit south of the tip. It was not until 2001 that they finally received a works authority. Much of the intervening 14 years had been taken up with compiling reports for Bass Coast Shire Council on the site’s flora and fauna, indigenous cultural heritage, groundwater and other environmental issues.

These included a 1994 Biosis report on the fauna of the gravel reserve by AS Kutt and JY Yugovic. They wrote that the Grantville gravel reserve and the adjoining conservation reserve "represent the southernmost remnant of native vegetation in a chain of partially connected remnants which collectively comprise most of the remaining native vegetation in West Gippsland, an area which is over 95 per cent cleared.

“Sand mining, residential development and land management are important issues affecting the future maintenance of these connections. Given these conflicting land-use pressures, gazetting this reserve should be a priority for regional conservation authorities.”

They concluded, "All vegetation communities [at the reserve] are considered to be of state (Grassy Woodland, Swamp Scrub) or regional (Dry Heathy Woodland, Dry Forest, Riparian Forest, Wet Heathy Woodland, Wet Scrub) conservation significance" (p58).

And they recommended that "consideration be given to transferring the south-eastern section of the gravel reserve, which includes the creek environment, to the adjacent nature reserve. This highly significant 17.5.ha area supports five vegetation communities, including Riparian Forest and Grassy Woodland".

In 1996 a regional sand extraction strategy adopted the recommendation and addressed the need to maintain vegetation linkages between the Grantville nature reserve/gravel reserve and areas of native vegetation further north, to facilitate wildlife movement and enhance reserve viability.

The strategy also listed significant flora, such as the green-lined greenhood and cobra greenhood, and fauna, such as the giant Gippsland earthworm and orange-bellied parrot and swift parrot, in the Grantville gravel reserve.

*****

In 2001, despite the copious information on significant flora and fauna, Sand Supplies was granted a work authority (originally a lease) to quarry sand. In view of the conservation status of much of the land, Bass Coast Shire Council imposed strict conditions on the miner. The company was required to retain all soil on site and progressively rehabilitate and revegetate the site, with a bond of hundreds of thousands of dollars and a possible gaol term for non-compliance.

The works authority stipulated that native vegetation could only be “removed, destroyed or lopped to the minimum extent necessary” to mine the sand in accordance with the work plan.

While many would argue conserving remnant pre-European native flora in the Grantville Nature Conservation Reserve and surrounds should take priority over extracting sand, Robbie Viglietti believes there has to be a trade-off to meet society’s needs for construction materials.

The works authority stipulated that native vegetation could only be “removed, destroyed or lopped to the minimum extent necessary” to mine the sand in accordance with the work plan.

While many would argue conserving remnant pre-European native flora in the Grantville Nature Conservation Reserve and surrounds should take priority over extracting sand, Robbie Viglietti believes there has to be a trade-off to meet society’s needs for construction materials.

*****

In autumn, 2021, he plans to start further excavation into the bush north-east of the grass tree forest. He points out that he likes grass trees too, and is committed to fulfilling the terms of his work authority to translocate grass trees to an excavated area on the north-west corner of the gravel reserve. A contractor is experimenting with the translocation. So far, he has dug up 28 grass trees, a mixture of ages and sizes, and replanted them off-site, and only one has died.

“The grass trees tend to grow in clusters, and I’m trying to replicate what we see in the natural world. To the untrained eye, it would look like native bush.

He is also keen to work with the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria to establish a forest of local grass trees at the Cranbourne Gardens.

However, experts, including Melbourne University’s Dr Mary Cole, say mature grass trees, some up to 600 years old and two metres tall, are unlikely to survive transplantation. Even if they do, at risk is an ecological system that has taken millions of years to evolve. What about the flying duck and other precious native orchids, wildflowers and other plants? What about the wildlife dependent on the forest?

Asked if it’s possible to do any sort of land swap, Robbie Viglietti says: “If you can find an alternative site for the sort of sand, the perfect sand with the right grading to do all the works we do, and we can get it without cutting down a tree and we can do it tomorrow, without having to go through another cumbersome 14 years of bureaucratic red tape, I would consider excising the grass tree forest from my work authority.”

“We can’t just decide where we can open a quarry. Nature decides that.”

But he pledges to use his best endeavours and preserve as much native bush as he can. “Where I create disturbance, I will restore it. I am committed to rehabilitation. I will disturb significant numbers of trees but I do have to preserve them. It’s not cursory. It took five consecutive years of surveys to determine specific examples of vegetation and come up with formulae to guarantee survival of trees.

“When we do finish up at the site, there will be a lag of one to two years after excavation and then rehabilitation occurs. The site will go back to Her Majesty and be accessible to the public again.”

“The grass trees tend to grow in clusters, and I’m trying to replicate what we see in the natural world. To the untrained eye, it would look like native bush.

He is also keen to work with the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria to establish a forest of local grass trees at the Cranbourne Gardens.

However, experts, including Melbourne University’s Dr Mary Cole, say mature grass trees, some up to 600 years old and two metres tall, are unlikely to survive transplantation. Even if they do, at risk is an ecological system that has taken millions of years to evolve. What about the flying duck and other precious native orchids, wildflowers and other plants? What about the wildlife dependent on the forest?

Asked if it’s possible to do any sort of land swap, Robbie Viglietti says: “If you can find an alternative site for the sort of sand, the perfect sand with the right grading to do all the works we do, and we can get it without cutting down a tree and we can do it tomorrow, without having to go through another cumbersome 14 years of bureaucratic red tape, I would consider excising the grass tree forest from my work authority.”

“We can’t just decide where we can open a quarry. Nature decides that.”

But he pledges to use his best endeavours and preserve as much native bush as he can. “Where I create disturbance, I will restore it. I am committed to rehabilitation. I will disturb significant numbers of trees but I do have to preserve them. It’s not cursory. It took five consecutive years of surveys to determine specific examples of vegetation and come up with formulae to guarantee survival of trees.

“When we do finish up at the site, there will be a lag of one to two years after excavation and then rehabilitation occurs. The site will go back to Her Majesty and be accessible to the public again.”

*****

The aftermath of last year’s Grantville bushfires has drawn attention to this magnificent grass tree forest. Now it’s up to us – community members, bureaucrats, politicians and, hopefully, sand miners – to protect them.

Maybe, with good will on both sides, it is possible to work out a trade-off so Mr Viglietti gets his sand while the community retains its spectacular and priceless grass tree forest.

Most urgently I urge the council to transfer the south-eastern section of the gravel reserve, which includes the creek environment, to the Grantville Nature Conservation Reserve.

We need an updated Biosis report on the whole Grantville reserve complex. The Grantville grass tree forest must be mapped and protected in perpetuity to ensure that none of its grass trees can be removed, destroyed, lopped or translocated.

Perhaps it’s also time to reactivate the dormant Bass Valley & District Branch of the South Gippsland Conservation Society to work on this and other local issues. Anyone interested please contact me on [email protected].

Sources

Maybe, with good will on both sides, it is possible to work out a trade-off so Mr Viglietti gets his sand while the community retains its spectacular and priceless grass tree forest.

Most urgently I urge the council to transfer the south-eastern section of the gravel reserve, which includes the creek environment, to the Grantville Nature Conservation Reserve.

We need an updated Biosis report on the whole Grantville reserve complex. The Grantville grass tree forest must be mapped and protected in perpetuity to ensure that none of its grass trees can be removed, destroyed, lopped or translocated.

Perhaps it’s also time to reactivate the dormant Bass Valley & District Branch of the South Gippsland Conservation Society to work on this and other local issues. Anyone interested please contact me on [email protected].

Sources

- 'Fauna of the Grantville Gravel Reserve, with Reference to Vegetation and Conservation Significance' by by AS Kutt and JY Yugovic, Biosis, 1994

- Regional Sand Extraction Strategy: Lang Lang to Grantville, October, 1996