Being part of a democratic community includes a responsibility to defend that community when necessary, writes Rod Gallagher in his essay on Australia and conscription.

Part 1

IN Still Spoiling for a fight (April 25, 2015, Frank Coldebella stated that during World War I “Australia voted against conscription in two referendums. (Wonthaggi voted no, although Victoria voted yes.)”

Not quite true, but I initially made a similar error when researching this article. Victoria voted “Yes” in the 1916 plebiscite but “No” in the 1917 plebiscite.

Did Wonthaggi have some great role to play in the Australian conscription debate? No. The town was just one of many communities who at the time actively argued again conscription, although it would be an interesting topic for some of our learned local historians to research the views about conscription held by others in the surrounding district at the time.

The important fact in the debate is that Australia was the only country during the period which allowed a democratic vote by plebiscite on the subject. Canada introduced conscription in 1917 but, facing an election, the government made it an election issue, modifying the electoral voting rules to include disenfranchised people, including Canadian women, who they felt might support conscription. But Canada never put a specific conscription question to their populace.

In any case, for both countries this vote shook the social fabric of each nation and continues to do so in many ways today. Britain has had conscription on only two occasions: World War I, commencing in 1916, and World War II. At other times it has relied on volunteer military service. Following the final defeat of Napoleon, it was British policy in the 19th and early 20th centuries not to be actively engaged in continental Europe. Large standing armies were not seen to be part of long-standing British culture.

In World War I, France, Germany, US, Italy, Balkans and Ottoman Turkey all had universal conscription with no choice in the matter, and in some cases impressment of men. Today, in Europe, Austria, Greece, Switzerland, Norway, Russia and Turkey still have active conscription. Many other states have abolished conscription but reserve the power to implement it in times of crisis, as allowed in Australia by the Constitution as reserve powers.

The two conscription plebiscites held during World War 1 caused great bitterness, divided much along sectarian, cultural and political lines, both in the general Australian community and within the governing Labor Party of the day. But in the case of Australia you cannot draw general conclusions by reporting particular examples. Many Irish expats and their descendants resisted it through hate of British home rule, but many did not. There were many Protestant Irish in Australia.

Trade unions were less concerned about social justice issues than the effect on wages and conditions. The worry was that working men who left their jobs to become soldiers would be replaced by cheap migrant labour and the hard-won rights fought for by unions would be lost.

“White Australia arguments” were used by sections of the Labor Party of the day to resist conscription. Some also believed conscription would make workers slaves of the military. A common view in accord with the Second International Comintern on worker rights, a movement that was seriously conflicted by World War I.

The Catholic Church in Australia had a neutral stance. Melbourne’s future Catholic Archbishop Daniel Mannix, an Irishman, strongly opposed conscription but not from the pulpit. The Archbishop of Sydney held the opposing view. The Anglian church accepted support for Britain to be a moral obligation, but not all individual ministers supported conscription. An individual Anglican minster telling a person that he had a moral obligation to volunteer in World War I can’t be represented as a universal view of all such ministers. There was a small but strong Anglian peace movement at the time.

By 1880 Australia had developed into an identifiable Anglo-Celtic culture with a strong liberal democratic tradition which actively resisted issues such as conscription, justified by its advocates on the grounds that under certain circumstances liberty must be subordinated to duty to the state or the community at large. In Australia this resistance was maintained in World War I and continues today. While conscription runs counter to the ideal of liberty and the primacy of the rights of the individual, and can be considered a form of coercion, there is the argument that under certain circumstances liberty must be subordinated to duty to the community at large to keep it safe.

In Australia, the question remains as to what constitutes the kind of threat to warrant exercising conscription to protect our democracy.

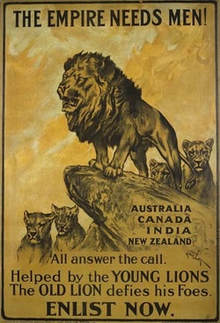

Before 1915 there were very few who asserted that men might be compelled to serve in armies beyond Australian territorial boundaries. The question was whether Australia had an obligation to assist Britain in time of war. It was felt at the time that Australians would volunteer in sufficient numbers in the defence of the Empire. The traditional objection to compelling men to fight outside the country was rooted in the belief, developed over the previous 30 years, that Australia was, or ought to be, free from “militarism”, a characteristic form of social oppression in older countries. However, the practical fact was that Dominion countries, including Australia, were not considered to be sovereign powers and possessed no independent foreign policy, since relations with other countries were determined by Great Britain at the time.

Were Australians, then, to be forced to fight in wars which their government had no part in making or any direct interest in prosecuting? It seemed essential that Australia should not be drawn into imperial ventures or caught up in struggles for power in Europe, but that proved an impossible dream.

In those countries that established a liberal tradition in the 19th century, the introduction of compulsory military service aroused deep controversies. In Britain it contributed to the divisions in the Liberal Party in 1915; in Canada, Australia and New Zealand it has provoked wide-ranging debate and sometimes political crisis. In Australia, the debate on conscription has continued since the founding of the Commonwealth in 1901. No other issue has divided the Australian community so sharply.

What people miss is the outcome for Australia, Canada and New Zealand at the end of World War I. These countries became truly independent of Britain and were able to make their own policies and express sovereign views and would no longer just accept British direction. The Dominion had moved on to the Commonwealth in its current form. For Australia this process of devolvement was completed in 1943-44, when, under the Labour Government, Australia aligned itself with the US.

I am a conscript, a detestable term in my view. National Serviceman, perhaps; citizen soldier, yes. During the Vietnam conflict, some 63,735 men from a 20-year-old cohort of 804,236 were called for National Service, with 18,735, or 2.3 per cent of the cohort, serving in Vietnam. In that period, 99,010 were rejected on physical grounds, there were 1242 conscientious objectors and only 14 men, including the famous Simon Townsend, refused the direction to obey the call-up notice. If you were born between 1945 and 1946 you had a one in six chance of call up. Between 1947 and 1972, you had a one in 12 chance. The first cohorts called up were 98 per cent Anglo-Celtic, with this ratio reducing in later intakes. The aim was to provide men at the rate of 8400 per year for the Army during this period.

The McMahon Government commenced the drawdown of Australian units from Vietnam 1971 in conjunction with the US policy of Vietnamisation of the conflict. The Whitlam Government completed the process and cancelled conscription when they came to power. This action did not mean that Whitlam was against conscription. He was very careful from 1966 to maintain the US alliances, but he and his deputy, Lionel Bowen, were World War II veterans and felt that conscription should only be used for the immediate defence of Australia in serious circumstances. Vietnam did not meet that criteria.

Whenever the issue of National Service (conscription) is raised, it’s almost always for the wrong reasons, and the vast majority of the armed forces in Australia are against it. Typically people favour it as a way of “sorting out” youths and giving them some discipline. This is the worst possible reason for supporting conscription.

But then the general public also wants to feel safe and secure. So the perennial question remains about how a democratic country defends itself when the population won’t pay for a sufficient professional volunteer deterrence and doesn’t want conscription. Certainly diplomacy won’t provide that security alone.

You cannot have your individual rights within a democratic community without accepting the responsibilities that go with it, including exercising the right to vote and to defend that community. However, there is that nice warm feeling when others do it for you.

Part 2

It’s arrogant to judge Australia’s actions of 100 years ago in terms of post-modern, liberal thought, argues Rod Gallagher in the second part of his essay on Australia’s involvement in the First World War.

FROM a distance of 100 years, the wringing of hands and brow-beating in suggesting that an aggressive Australia was spoiling for a fight in 1915 (Still spoiling for a fight, Frank Coldebella, April 25, 2015) is uninformed intellectual nonsense and not supported by history.

It’s also silly to suggest that we as a country invaded a Turkey defending itself from imperialist aggression in 1915. Gallipoli was a legitimate military campaign against a belligerent in the context of the time. It should not be lost that a number of Turks preferred the British to the Germans or the Russians, particularly the latter because their demand was the annexure of all European Turkey in the name of saving the Slavic races. And note that today those basic animosities in this region and the Middle East have not changed.

Of course when Germany breached Belgium sovereignty 1914 they were not spoiling for a fight! And in the Balkan Wars of 1912-13, Ottoman Turkey, Serbia, Bulgaria, Greece and Montenegro, with Russia cheering on the side lines, were also not spoiling for a fight, but simply sorting out local interests. And let us not forget that recently formed new European nation, Italy. In 1911 that country invaded the Ottoman Province of Libya and Somaliland, plus the Dodecanese islands in the Aegean Sea, helped in no small way by the large scale lobbying by the Italian press for the campaign. Many historians attribute this action taken by Italy to be a major precursor to World War One because it sparked the Balkan nationalism that led to the 1912-13 conflicts in that area. So much for Australia invading a defenceless Muslim country, Turkey, in 1915.

Nor should one overlook Italy’s behaviour in reaching its decision to enter World War I. In effect it auctioned its support to the highest bidder.

So what was Ottoman Turkey doing at this time other than being racked by internal dissent and looking squarely at internal revolution leading to devolvement of the Ottoman Empire? They joined an alliance with Germany on August 2, 1914, with the aim of recovering territories lost in Eastern Anatolia to Russia in earlier wars. The Germans hoped success in this region would force the Russians to divert troops from the Polish and Galician fronts. The Germans also had an economic interest with objectives to cut off Russian access to oil round the Caspian Sea, put pressure on the Russian fronts, pressure Persia to sever ties with Britain and threaten the Suez Canal. If successful, Ottoman Turkey would again establish hegemony over its lost Middle Eastern provinces and Egypt.

Colonial Australia’s involvement in the Sudan, Second Boer War and the concurrent Boxer Rebellion was not about any unilateral invasion policy of Australia at the time but a complex defence relationship between the colonies and the Britain. In all instances Britain requested support under colonial defence obligations. Bear in mind that British forces and navy units were stationed in Australia until 1870 for colonial protection and on leaving there was an expectation that the new states would participate in defence of the Realm.

World War II and Korea stand apart. The same cannot be said for Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan. As a Vietnam veteran, I am still conflicted over Vietnam. In the latter Middle Eastern countries, I would be quiet happy to let these people sort out their own problems even if it means many tens of thousands will die. At some stage, through sheer exhaustion, they will stop killing one another and do something positive. That may even mean another dictatorship; the French have suggested a supported monarchy as best suiting the cultural differences in the Middle East. Liberals can talk about their “human and democratic rights”. That means you need to accept democracy as the only construct in which to exercise these rights, but I accept that there are other legitimate systems of government in which human rights can exist and be nurtured.

To judge Australia’s behaviour and choices made 100 years ago in terms of post-modern, liberal and narrow-minded, socialist left thought is intellectual arrogance. It is concerning today to see the increasing habit by academia and intellectuals to engage in the censorship of ideas not in accord with their thinking by arguing academic integrity or simply that they know best. For example, the recent closure of the Longborg Consensus Centre at the University of Western Australia. Yes, “Longborg” is wacky, but you fight his ideas by aggressive logical debate, not through academic censorship or by arguing that you need to protect young students from “poor science”. A university is nothing without the engagement of all ideas. By the way, I am no supporter of the likes of the “Bolts” of this world.

The Australian Constitution is rather vague about who can declare war. Many point to other democratic countries where this requires a parliamentary debate. Here in Australia, the Prime Minister and Cabinet can commit Australian forces to legitimate security operations in support of treaties if it is gauged to be in Australia’s interests. You can argue what that can be. Convention requires that the Leader of the Opposition be consulted and can raise any decision for debate in Parliament and the public. The Prime Minister also needs the Foreign Minister and the Security Council on board because they advise of the international implications of any such decision and whether the Australian Defence Force has the resources to support the proposed action. Patently, it does not have the capacity to support brigade-sized operations and is not militaristic by nature in terms of the accepted definitions of militarism. As an example of the checks and balances in our system of government, if the Government decides to go to war which requires conscription, then conscription must now be put to both houses of Parliament, which means serious public scrutiny with political and electoral consequences. The hordes will need to be howling on our country’s shore before conscription is ever introduced again in Australia.

History shows that Australia alone has not engaged in self-interested military acts, and has only invaded one country once: Portuguese Timor in 1942 to deny the island to the Japanese, and that was not successful.

For every statement in Frank Coldebella’s article pondering the forgotten lessons of Gallipoli I could find similar examples of bad behaviour perpetrated by the military of other countries. For negative statement about the so-called bad behaviour of Australian troops, I can give 10 times as many examples of outstanding humanity expressed by Australian soldiers. In recent times, consider their involvement in Rwanda or after the Indonesian tsunami when the RAAF was on the ground within hours.

I know Australian troops killed Japanese prisoners on occasion, but read about the Japanese massacres at the Toll Plantation or the brothers from Wonthaggi executed by the Japanese in Timor at the end of World War II. By excluding those examples, he implies that our behaviour was unique and the worst.

I am tired of the self-loathing of my country expressed by some Australians with narrow, bigoted views that they claim to be objective assessments of our history.

Rod Gallagher is an Inverloch military historian and Vietnam veteran.

COMMENTS

Rod Gallagher is right, of course, you can't judge the actions of one hundred years ago by our standards, but you can judge our actions; and, speaking as a fairly recent blow-in from England, I would say that Australia seems to edging perilously close to celebrating those terrible events rather than commemorating them.

Mark Chevning, Wonthaggi

IN Still Spoiling for a fight (April 25, 2015, Frank Coldebella stated that during World War I “Australia voted against conscription in two referendums. (Wonthaggi voted no, although Victoria voted yes.)”

Not quite true, but I initially made a similar error when researching this article. Victoria voted “Yes” in the 1916 plebiscite but “No” in the 1917 plebiscite.

Did Wonthaggi have some great role to play in the Australian conscription debate? No. The town was just one of many communities who at the time actively argued again conscription, although it would be an interesting topic for some of our learned local historians to research the views about conscription held by others in the surrounding district at the time.

The important fact in the debate is that Australia was the only country during the period which allowed a democratic vote by plebiscite on the subject. Canada introduced conscription in 1917 but, facing an election, the government made it an election issue, modifying the electoral voting rules to include disenfranchised people, including Canadian women, who they felt might support conscription. But Canada never put a specific conscription question to their populace.

In any case, for both countries this vote shook the social fabric of each nation and continues to do so in many ways today. Britain has had conscription on only two occasions: World War I, commencing in 1916, and World War II. At other times it has relied on volunteer military service. Following the final defeat of Napoleon, it was British policy in the 19th and early 20th centuries not to be actively engaged in continental Europe. Large standing armies were not seen to be part of long-standing British culture.

In World War I, France, Germany, US, Italy, Balkans and Ottoman Turkey all had universal conscription with no choice in the matter, and in some cases impressment of men. Today, in Europe, Austria, Greece, Switzerland, Norway, Russia and Turkey still have active conscription. Many other states have abolished conscription but reserve the power to implement it in times of crisis, as allowed in Australia by the Constitution as reserve powers.

The two conscription plebiscites held during World War 1 caused great bitterness, divided much along sectarian, cultural and political lines, both in the general Australian community and within the governing Labor Party of the day. But in the case of Australia you cannot draw general conclusions by reporting particular examples. Many Irish expats and their descendants resisted it through hate of British home rule, but many did not. There were many Protestant Irish in Australia.

Trade unions were less concerned about social justice issues than the effect on wages and conditions. The worry was that working men who left their jobs to become soldiers would be replaced by cheap migrant labour and the hard-won rights fought for by unions would be lost.

“White Australia arguments” were used by sections of the Labor Party of the day to resist conscription. Some also believed conscription would make workers slaves of the military. A common view in accord with the Second International Comintern on worker rights, a movement that was seriously conflicted by World War I.

The Catholic Church in Australia had a neutral stance. Melbourne’s future Catholic Archbishop Daniel Mannix, an Irishman, strongly opposed conscription but not from the pulpit. The Archbishop of Sydney held the opposing view. The Anglian church accepted support for Britain to be a moral obligation, but not all individual ministers supported conscription. An individual Anglican minster telling a person that he had a moral obligation to volunteer in World War I can’t be represented as a universal view of all such ministers. There was a small but strong Anglian peace movement at the time.

By 1880 Australia had developed into an identifiable Anglo-Celtic culture with a strong liberal democratic tradition which actively resisted issues such as conscription, justified by its advocates on the grounds that under certain circumstances liberty must be subordinated to duty to the state or the community at large. In Australia this resistance was maintained in World War I and continues today. While conscription runs counter to the ideal of liberty and the primacy of the rights of the individual, and can be considered a form of coercion, there is the argument that under certain circumstances liberty must be subordinated to duty to the community at large to keep it safe.

In Australia, the question remains as to what constitutes the kind of threat to warrant exercising conscription to protect our democracy.

Before 1915 there were very few who asserted that men might be compelled to serve in armies beyond Australian territorial boundaries. The question was whether Australia had an obligation to assist Britain in time of war. It was felt at the time that Australians would volunteer in sufficient numbers in the defence of the Empire. The traditional objection to compelling men to fight outside the country was rooted in the belief, developed over the previous 30 years, that Australia was, or ought to be, free from “militarism”, a characteristic form of social oppression in older countries. However, the practical fact was that Dominion countries, including Australia, were not considered to be sovereign powers and possessed no independent foreign policy, since relations with other countries were determined by Great Britain at the time.

Were Australians, then, to be forced to fight in wars which their government had no part in making or any direct interest in prosecuting? It seemed essential that Australia should not be drawn into imperial ventures or caught up in struggles for power in Europe, but that proved an impossible dream.

In those countries that established a liberal tradition in the 19th century, the introduction of compulsory military service aroused deep controversies. In Britain it contributed to the divisions in the Liberal Party in 1915; in Canada, Australia and New Zealand it has provoked wide-ranging debate and sometimes political crisis. In Australia, the debate on conscription has continued since the founding of the Commonwealth in 1901. No other issue has divided the Australian community so sharply.

What people miss is the outcome for Australia, Canada and New Zealand at the end of World War I. These countries became truly independent of Britain and were able to make their own policies and express sovereign views and would no longer just accept British direction. The Dominion had moved on to the Commonwealth in its current form. For Australia this process of devolvement was completed in 1943-44, when, under the Labour Government, Australia aligned itself with the US.

I am a conscript, a detestable term in my view. National Serviceman, perhaps; citizen soldier, yes. During the Vietnam conflict, some 63,735 men from a 20-year-old cohort of 804,236 were called for National Service, with 18,735, or 2.3 per cent of the cohort, serving in Vietnam. In that period, 99,010 were rejected on physical grounds, there were 1242 conscientious objectors and only 14 men, including the famous Simon Townsend, refused the direction to obey the call-up notice. If you were born between 1945 and 1946 you had a one in six chance of call up. Between 1947 and 1972, you had a one in 12 chance. The first cohorts called up were 98 per cent Anglo-Celtic, with this ratio reducing in later intakes. The aim was to provide men at the rate of 8400 per year for the Army during this period.

The McMahon Government commenced the drawdown of Australian units from Vietnam 1971 in conjunction with the US policy of Vietnamisation of the conflict. The Whitlam Government completed the process and cancelled conscription when they came to power. This action did not mean that Whitlam was against conscription. He was very careful from 1966 to maintain the US alliances, but he and his deputy, Lionel Bowen, were World War II veterans and felt that conscription should only be used for the immediate defence of Australia in serious circumstances. Vietnam did not meet that criteria.

Whenever the issue of National Service (conscription) is raised, it’s almost always for the wrong reasons, and the vast majority of the armed forces in Australia are against it. Typically people favour it as a way of “sorting out” youths and giving them some discipline. This is the worst possible reason for supporting conscription.

But then the general public also wants to feel safe and secure. So the perennial question remains about how a democratic country defends itself when the population won’t pay for a sufficient professional volunteer deterrence and doesn’t want conscription. Certainly diplomacy won’t provide that security alone.

You cannot have your individual rights within a democratic community without accepting the responsibilities that go with it, including exercising the right to vote and to defend that community. However, there is that nice warm feeling when others do it for you.

Part 2

It’s arrogant to judge Australia’s actions of 100 years ago in terms of post-modern, liberal thought, argues Rod Gallagher in the second part of his essay on Australia’s involvement in the First World War.

FROM a distance of 100 years, the wringing of hands and brow-beating in suggesting that an aggressive Australia was spoiling for a fight in 1915 (Still spoiling for a fight, Frank Coldebella, April 25, 2015) is uninformed intellectual nonsense and not supported by history.

It’s also silly to suggest that we as a country invaded a Turkey defending itself from imperialist aggression in 1915. Gallipoli was a legitimate military campaign against a belligerent in the context of the time. It should not be lost that a number of Turks preferred the British to the Germans or the Russians, particularly the latter because their demand was the annexure of all European Turkey in the name of saving the Slavic races. And note that today those basic animosities in this region and the Middle East have not changed.

Of course when Germany breached Belgium sovereignty 1914 they were not spoiling for a fight! And in the Balkan Wars of 1912-13, Ottoman Turkey, Serbia, Bulgaria, Greece and Montenegro, with Russia cheering on the side lines, were also not spoiling for a fight, but simply sorting out local interests. And let us not forget that recently formed new European nation, Italy. In 1911 that country invaded the Ottoman Province of Libya and Somaliland, plus the Dodecanese islands in the Aegean Sea, helped in no small way by the large scale lobbying by the Italian press for the campaign. Many historians attribute this action taken by Italy to be a major precursor to World War One because it sparked the Balkan nationalism that led to the 1912-13 conflicts in that area. So much for Australia invading a defenceless Muslim country, Turkey, in 1915.

Nor should one overlook Italy’s behaviour in reaching its decision to enter World War I. In effect it auctioned its support to the highest bidder.

So what was Ottoman Turkey doing at this time other than being racked by internal dissent and looking squarely at internal revolution leading to devolvement of the Ottoman Empire? They joined an alliance with Germany on August 2, 1914, with the aim of recovering territories lost in Eastern Anatolia to Russia in earlier wars. The Germans hoped success in this region would force the Russians to divert troops from the Polish and Galician fronts. The Germans also had an economic interest with objectives to cut off Russian access to oil round the Caspian Sea, put pressure on the Russian fronts, pressure Persia to sever ties with Britain and threaten the Suez Canal. If successful, Ottoman Turkey would again establish hegemony over its lost Middle Eastern provinces and Egypt.

Colonial Australia’s involvement in the Sudan, Second Boer War and the concurrent Boxer Rebellion was not about any unilateral invasion policy of Australia at the time but a complex defence relationship between the colonies and the Britain. In all instances Britain requested support under colonial defence obligations. Bear in mind that British forces and navy units were stationed in Australia until 1870 for colonial protection and on leaving there was an expectation that the new states would participate in defence of the Realm.

World War II and Korea stand apart. The same cannot be said for Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan. As a Vietnam veteran, I am still conflicted over Vietnam. In the latter Middle Eastern countries, I would be quiet happy to let these people sort out their own problems even if it means many tens of thousands will die. At some stage, through sheer exhaustion, they will stop killing one another and do something positive. That may even mean another dictatorship; the French have suggested a supported monarchy as best suiting the cultural differences in the Middle East. Liberals can talk about their “human and democratic rights”. That means you need to accept democracy as the only construct in which to exercise these rights, but I accept that there are other legitimate systems of government in which human rights can exist and be nurtured.

To judge Australia’s behaviour and choices made 100 years ago in terms of post-modern, liberal and narrow-minded, socialist left thought is intellectual arrogance. It is concerning today to see the increasing habit by academia and intellectuals to engage in the censorship of ideas not in accord with their thinking by arguing academic integrity or simply that they know best. For example, the recent closure of the Longborg Consensus Centre at the University of Western Australia. Yes, “Longborg” is wacky, but you fight his ideas by aggressive logical debate, not through academic censorship or by arguing that you need to protect young students from “poor science”. A university is nothing without the engagement of all ideas. By the way, I am no supporter of the likes of the “Bolts” of this world.

The Australian Constitution is rather vague about who can declare war. Many point to other democratic countries where this requires a parliamentary debate. Here in Australia, the Prime Minister and Cabinet can commit Australian forces to legitimate security operations in support of treaties if it is gauged to be in Australia’s interests. You can argue what that can be. Convention requires that the Leader of the Opposition be consulted and can raise any decision for debate in Parliament and the public. The Prime Minister also needs the Foreign Minister and the Security Council on board because they advise of the international implications of any such decision and whether the Australian Defence Force has the resources to support the proposed action. Patently, it does not have the capacity to support brigade-sized operations and is not militaristic by nature in terms of the accepted definitions of militarism. As an example of the checks and balances in our system of government, if the Government decides to go to war which requires conscription, then conscription must now be put to both houses of Parliament, which means serious public scrutiny with political and electoral consequences. The hordes will need to be howling on our country’s shore before conscription is ever introduced again in Australia.

History shows that Australia alone has not engaged in self-interested military acts, and has only invaded one country once: Portuguese Timor in 1942 to deny the island to the Japanese, and that was not successful.

For every statement in Frank Coldebella’s article pondering the forgotten lessons of Gallipoli I could find similar examples of bad behaviour perpetrated by the military of other countries. For negative statement about the so-called bad behaviour of Australian troops, I can give 10 times as many examples of outstanding humanity expressed by Australian soldiers. In recent times, consider their involvement in Rwanda or after the Indonesian tsunami when the RAAF was on the ground within hours.

I know Australian troops killed Japanese prisoners on occasion, but read about the Japanese massacres at the Toll Plantation or the brothers from Wonthaggi executed by the Japanese in Timor at the end of World War II. By excluding those examples, he implies that our behaviour was unique and the worst.

I am tired of the self-loathing of my country expressed by some Australians with narrow, bigoted views that they claim to be objective assessments of our history.

Rod Gallagher is an Inverloch military historian and Vietnam veteran.

COMMENTS

Rod Gallagher is right, of course, you can't judge the actions of one hundred years ago by our standards, but you can judge our actions; and, speaking as a fairly recent blow-in from England, I would say that Australia seems to edging perilously close to celebrating those terrible events rather than commemorating them.

Mark Chevning, Wonthaggi