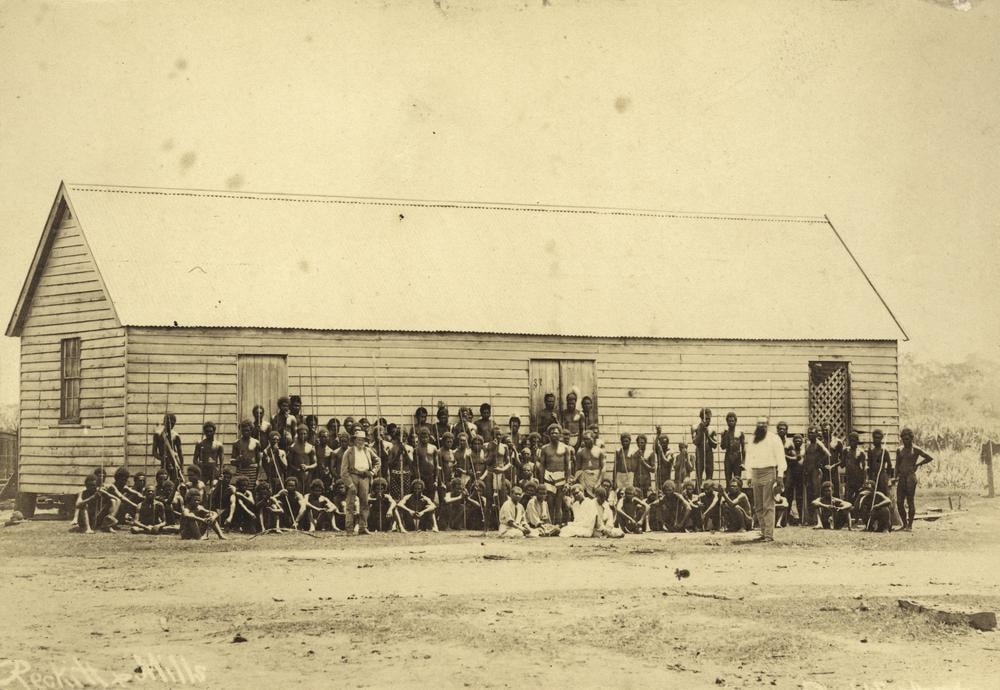

Pacific Island labourers were 'recruited' by dubious means

Pacific Island labourers were 'recruited' by dubious means to work on Queensland's sugarcane plantations.

Photo: State Library Of Queensland

A VERY distinguished tall dark-skinned man walked into sight. I asked my uncle George who he was. Oh, that’s a descendant of the Kanaks. Who? They came out from the Islands to help in the sugar cane fields. He’s one of the richest farmers in the district now.

I could hear the resentment in his voice. Uncle George still cut his cane fields by hand, hated Queensland’s then premier Joh Bjelke Petersen and the gerrymander and found life very hard. It hadn’t rained for five years.

The year is 1968. I am visiting an aunt and uncle who were cane farmers just south of Mackay. My paternal grandfather moved into the area in the 1920s, and my father was born in Mackay.

My grandparents, Harry and Elizabeth

My grandparents, Harry and Elizabeth Smith (nee German)

Fascinated by this tall, dark distinguished man, I delved into where exactly the island of Kanak was. My many relatives still living in the area were very tight lipped and I soon learnt why – slavery is a touchy issue – although there is no evidence that they were involved in the exploitation of slaves.

Here is a glimpse of where my research took me.

South Sea Islanders (Kanaks) are the indigenous Melanesian inhabitants of New Caledonia, an overseas territory of France in the southwest Pacific. According to the 2014 census, they make up 39 per cent of the total population, with around 105,000 people. “Kanak” people prefer to be called South Sea Islanders.

The first Islander “immigrants” to Australia were mostly young males aged between 15 and 35; only 6 percent were women. Historians agree that the initial phase of “recruiting” in most areas was by deception, kidnapping or coercion, a practice known as “black-birding”.

As the black- birding trade progressed, the next generation followed into the labour trade vessels, lured not so much by outright trickery as by the goods offered by beguiling recruiters and the chance to better themselves when they returned to their home societies after three years.

South Sea Islander women working in the sugarcane fields at Hambledon, Queensland, circa 1891.

South Sea Islander women working in the sugarcane fields at Hambledon, Queensland, circa 1891. Photo: CityLibraries Townsville, Local History Collection

They were also only provided with a weekly food ration and their hours of work were unlimited. Britain had abolished slavery throughout the British Empire with the passing of Abolition Act in July 1833. However, descendants of the Islanders all tell similar stories about their ancestors not understanding English, being stolen and coerced and treated “like slaves” once they arrived. The majority of South Sea Islanders in Australia consider themselves to be descendants of kidnapped slaves, not indentured labourers.

While the method of their recruitment remains debated, what is more certain is the high cost in human lives in the largely circular migration. On average, 50 Melanesians in every 1000 died each year in Queensland. In 1884, the death rate was 147 per 1000, compared with a death rate of around 9 or 10 per 1000 among European males of the same age in the colony.

The primary causes of death were exposure to bacillary dysentery, pneumonia and tuberculosis, against which the new recruits had little immunity. An estimated 15,000 died within the first year or so of arriving due to these diseases, mistreatment and malnutrition. When they died their bodies were buried together in mass unmarked graves, some of which continue to be discovered today.

Queensland is huge, two and a half times as big as Texas. Until about 1880 the Islanders could be employed in any pastoral or maritime industry in the colony, but thereafter they were restricted to the sugar industry along the east coast. The majority were from 80 islands in Melanesia, mainly those included in the New Hebrides (present-day Vanuatu) and the Solomon Islands, but also from the Loyalty Islands off New Caledonia and the eastern archipelagos of Papua New Guinea, plus a few from Tuvalu and Kiribati. Roughly one third were from the Solomons and two-thirds from Vanuatu.

The major cities of Mackay and Townsville are named after men who participated in the blackbirding trade. The Pioneer Valley at Mackay, located midway between Brisbane and Cairns on the coast of central Queensland, is the largest sugar-producing area in Australia and has always had the largest Pacific Islander population, although the residual Islander community there is predominantly from the Solomon Islands.

Blackbirding ended after the introduction of the White Australia policy, in 1901, Surviving South Sea Islanders were forcibly deported to the Pacific, often to different islands and countries from their original homes. Today, approximately 15,000 Australians claim descent from Pacific Islanders. Around Mackay, they make up around 2500 of the 80,000 urban population. There are similar numbers of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders in the district.

This story is repeated in any colonised land. The misguided belief that your worth is determined by the colour of your skin, cultural differences and belief systems is discriminatory and just plain wrong. Sadly, I believe there will always be trafficking in human life, sex workers, sweatshop workers, etc.

To me, pretending slavery and oppression never happened by destroying historical references and monuments is just retreating into denial again.

My ancestors’ long association with the sugar industry causes me to cringe at times and I am depressed by the racist attitudes of the 1960s that still persist today. It is time we embraced cultural differences and shrugged off some of the white, middle class, privately schooled, predominately male, born-to-rule attitudes.

Sources

Consuming Whiteness: Australian Racism and the "White Sugar" Campaign Paperback – 1 December 2014 by Stefanie Affeldt (Author) From Sydney Criminal Lawyers home page.

Fitzpatrick, Judith M. (ed.), Endangered Peoples of Oceania: Struggles to Survive and Thrive, Westport (Ct), Greenwood Press, 2001 (pp 167-81).