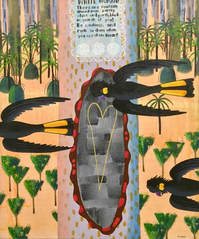

Scar tree with heart and yellowtail cockatoos, Rodney Forbes, 2014

Scar tree with heart and yellowtail cockatoos, Rodney Forbes, 2014 Scottish writer Cal Flyn confronted the truth of her ancestor Angus McMillan, a revered pioneer who perpetrated the slaughter of Gippsland’s Indigenous people.

By Jeannie Haughton

THE internet is a duplicitous sneak-thief, offering almost instant connection to the rest of the world, while stealing our time as we answer emails, check social media pages, read advertisements and the latest news or listen to opinions as diverse as the world expert on Zika virus.

But the internet brought me Scottish writer Cal Flyn and visual artist Rodney Forbes. Brought them into my life both digitally and then physically. We share a mutual interest in the white settlement of Gippsland and the frontier war that ensued when the local Indigenous mobs realised the settlers were not just passing through, were, in fact, fencing them out of their homelands.

What do I say to Cal Flyn when, months after our first email contact, we are on the trail of Gippsland’s founding “murdering” father, the man who perpetrated the slaughter of Indigenous people including the largest massacre at Warrigal Creek, and this man is her distant relative, the man she has come to Australia to know better? In Gippsland, Angus McMillan (1810-1865) has institutions, streets, parks even a tertiary institution named after him.

And what does Cal Flyn have to say about it all?

Well, she wrote a fine book. And it is intriguing, with hindsight, to have watched Thicker than Water come to life. It is well worth the read.

No lightweight book, it does make for easy reading as Flyn skilfully weaves family memoir, historical accounts, personal reflection and travel journal. Easy reading that is, if you can deal with the brutality inherent in the era she explores. Flyn asks herself how she feels about this ancestor, and how much, if any, guilt she should assume; she speculates as to what she may have done in the same situation.

Having written about McMillan for theatre, I also travelled to get a clearer picture of the man celebrated for founding Gippsland. This was years after a season of my play, Salute the Man, at Old Gippstown (2009), a heritage park in Moe which contains McMillan’s original homestead, Bushy Park.

I journeyed to the Hebrides, to the Isle of Barra, and Skye in Scotland to try to get inside the head of McMillan. I was following in the footsteps of other Australians, all bewildered by the differing accounts of white settlement in Gippsland, all seeking a clearer picture of this man’s multi-faceted deeds, of the ongoing impacts to this day for the surviving Indigenous generations, and for Australia as a nation.

Cal Flyn travelled in the opposite direction, from Scotland to Australia, following McMillan’s own journals, and for much the same reasons. For over a week we travelled together along the McMillan trail and to sites of Indigenous significance.

Rodney Forbes is a very fine artist whose tragi-comic exhibition, Lohan Tuka, The Lost White Woman of Gippsland, has been exhibited in Melbourne and Sale. His paintings are deliciously dark: his colourful, naïve works are laced with his wry humour, and are wittily observant while being historically accurate. There is much to think about when you spend time with his works.

There is also much to be learned from Thicker than Water’s historical and contemporary observations. Flyn takes us further into the core of Australian identity as she is drawn toward the subsequent story. Delving into government policies of assimilation with missions at Ramahyuck and, later, Lake Tyers, she dares to name the institutionalised inhumanity of treatment of Indigenous people and the systematic snuffing out of their culture. Genocide.

Cal Flyn’s book invites us as Australians to join her in her quest for McMillan, the man and his legacy. Undoubtedly a “man of his times”, very ambitious, and a murderer who knew that what he was doing was against the law, McMillan was also a determined, resourceful bushman who learned the Indigenous language and always travelled with Indigenous guides. He was a generous, hospitable host for Scottish immigrant families, and he dreamed of founding “Caledonia Australis”, a new and bountiful Scottish Australia for his starving kinsmen. Too bad for the Indigenous tribes who got in the way.

Importantly, Flyn tempts us to examine our complacency, the honesty of our historical accounts, and the shallowness of our storytelling lexicon.

Forbes’ visual works and my dramatic/performance texts based around McMillan and the mythical White Woman of Gippsland complement each other very well, and we have for some time worked on the idea of touring our works through Gippsland to broaden understanding and knowledge of those disturbing years.

We ask ourselves whether knowledge and acceptance of past wrongs leads to a clearer, stronger path forward for our communities.

Can our works be a catalyst for change, encouraging communities to engage honestly with the contemporary issues that beset our Indigenous communities, indeed our nation? Are they tools for healing or, as one woman accused, “might do more harm than good”?

Would a name change to the Electorate of McMillan, stripping the man of his honours be worthwhile, have genuine significance? Would it do anything beyond making us feel better about ourselves? It could be a step in the direction of recognising the ruthlessness of white settlement or another empty gesture.

Perhaps the internet, that which connects so many of us, has a further role to play in connecting this history with a broader audience, connecting me with you.

The thing is, there are no definitives to any of our searches. Like children poking sticks into bullant holes, we three artists and many others, seriously extend a challenge for Gippslanders in particular to be stung or feel anything, anything at all, about the white settlement of Australia.

Jeannie Haughton is a playwright, theatre producer and freelance writer. Her works have been produced in Melbourne and regionally, and in 2010 she co-founded Off The Leash Theatre in West Gippsland. Jeannie is currently the assistant artistic director of The Edge of Us, a Small Towns Transformation project that will play out in the Waterline townships of Corinella, Coronet Bay, Grantville, Pioneer Bay and Tenby Point over the next 18 months.

THE internet is a duplicitous sneak-thief, offering almost instant connection to the rest of the world, while stealing our time as we answer emails, check social media pages, read advertisements and the latest news or listen to opinions as diverse as the world expert on Zika virus.

But the internet brought me Scottish writer Cal Flyn and visual artist Rodney Forbes. Brought them into my life both digitally and then physically. We share a mutual interest in the white settlement of Gippsland and the frontier war that ensued when the local Indigenous mobs realised the settlers were not just passing through, were, in fact, fencing them out of their homelands.

What do I say to Cal Flyn when, months after our first email contact, we are on the trail of Gippsland’s founding “murdering” father, the man who perpetrated the slaughter of Indigenous people including the largest massacre at Warrigal Creek, and this man is her distant relative, the man she has come to Australia to know better? In Gippsland, Angus McMillan (1810-1865) has institutions, streets, parks even a tertiary institution named after him.

And what does Cal Flyn have to say about it all?

Well, she wrote a fine book. And it is intriguing, with hindsight, to have watched Thicker than Water come to life. It is well worth the read.

No lightweight book, it does make for easy reading as Flyn skilfully weaves family memoir, historical accounts, personal reflection and travel journal. Easy reading that is, if you can deal with the brutality inherent in the era she explores. Flyn asks herself how she feels about this ancestor, and how much, if any, guilt she should assume; she speculates as to what she may have done in the same situation.

Having written about McMillan for theatre, I also travelled to get a clearer picture of the man celebrated for founding Gippsland. This was years after a season of my play, Salute the Man, at Old Gippstown (2009), a heritage park in Moe which contains McMillan’s original homestead, Bushy Park.

I journeyed to the Hebrides, to the Isle of Barra, and Skye in Scotland to try to get inside the head of McMillan. I was following in the footsteps of other Australians, all bewildered by the differing accounts of white settlement in Gippsland, all seeking a clearer picture of this man’s multi-faceted deeds, of the ongoing impacts to this day for the surviving Indigenous generations, and for Australia as a nation.

Cal Flyn travelled in the opposite direction, from Scotland to Australia, following McMillan’s own journals, and for much the same reasons. For over a week we travelled together along the McMillan trail and to sites of Indigenous significance.

Rodney Forbes is a very fine artist whose tragi-comic exhibition, Lohan Tuka, The Lost White Woman of Gippsland, has been exhibited in Melbourne and Sale. His paintings are deliciously dark: his colourful, naïve works are laced with his wry humour, and are wittily observant while being historically accurate. There is much to think about when you spend time with his works.

There is also much to be learned from Thicker than Water’s historical and contemporary observations. Flyn takes us further into the core of Australian identity as she is drawn toward the subsequent story. Delving into government policies of assimilation with missions at Ramahyuck and, later, Lake Tyers, she dares to name the institutionalised inhumanity of treatment of Indigenous people and the systematic snuffing out of their culture. Genocide.

Cal Flyn’s book invites us as Australians to join her in her quest for McMillan, the man and his legacy. Undoubtedly a “man of his times”, very ambitious, and a murderer who knew that what he was doing was against the law, McMillan was also a determined, resourceful bushman who learned the Indigenous language and always travelled with Indigenous guides. He was a generous, hospitable host for Scottish immigrant families, and he dreamed of founding “Caledonia Australis”, a new and bountiful Scottish Australia for his starving kinsmen. Too bad for the Indigenous tribes who got in the way.

Importantly, Flyn tempts us to examine our complacency, the honesty of our historical accounts, and the shallowness of our storytelling lexicon.

Forbes’ visual works and my dramatic/performance texts based around McMillan and the mythical White Woman of Gippsland complement each other very well, and we have for some time worked on the idea of touring our works through Gippsland to broaden understanding and knowledge of those disturbing years.

We ask ourselves whether knowledge and acceptance of past wrongs leads to a clearer, stronger path forward for our communities.

Can our works be a catalyst for change, encouraging communities to engage honestly with the contemporary issues that beset our Indigenous communities, indeed our nation? Are they tools for healing or, as one woman accused, “might do more harm than good”?

Would a name change to the Electorate of McMillan, stripping the man of his honours be worthwhile, have genuine significance? Would it do anything beyond making us feel better about ourselves? It could be a step in the direction of recognising the ruthlessness of white settlement or another empty gesture.

Perhaps the internet, that which connects so many of us, has a further role to play in connecting this history with a broader audience, connecting me with you.

The thing is, there are no definitives to any of our searches. Like children poking sticks into bullant holes, we three artists and many others, seriously extend a challenge for Gippslanders in particular to be stung or feel anything, anything at all, about the white settlement of Australia.

Jeannie Haughton is a playwright, theatre producer and freelance writer. Her works have been produced in Melbourne and regionally, and in 2010 she co-founded Off The Leash Theatre in West Gippsland. Jeannie is currently the assistant artistic director of The Edge of Us, a Small Towns Transformation project that will play out in the Waterline townships of Corinella, Coronet Bay, Grantville, Pioneer Bay and Tenby Point over the next 18 months.

COMMENTS

July 20, 2016

Many thanks to the Bass Coast Post for such thought-provoking pieces.

I am so touched by the insights within Jeannie Haughton's sublime Our founding, murdering father. The efforts of Cal Flynn, Jeannie Haughton, Rodney Forbes, Annemieke Mein, Peter Gardner, Don Watson, and others take us on a journey and give us a burden.

When this federal electorate was proclaimed in 1948, misery and horror were cloaked in a shroud now cast aside.

Anne Jones, convenor of the West Gippsland Reconciliation Group, submitted to the 2002 Australian Electoral Commission’s Victorian redistribution. She closed with “We are concerned that by continuing to honour the names of people who massacred and mistreated the original inhabitants of this land, the integrity of the reconciliation process is called into question”.

Submissions were also made by other groups and individuals to the 2002 and 2010 redistributions.

The name remains. In February 2015 the AEC issued a set of guidelines for determining the names of federal electoral divisions.

The opportunity to rename this electorate returns in the last quarter of 2017 with the next AEC redistribution of Victoria.

Geoff Ellis, Wattle Bank

July 20, 2016

Many thanks to the Bass Coast Post for such thought-provoking pieces.

I am so touched by the insights within Jeannie Haughton's sublime Our founding, murdering father. The efforts of Cal Flynn, Jeannie Haughton, Rodney Forbes, Annemieke Mein, Peter Gardner, Don Watson, and others take us on a journey and give us a burden.

When this federal electorate was proclaimed in 1948, misery and horror were cloaked in a shroud now cast aside.

Anne Jones, convenor of the West Gippsland Reconciliation Group, submitted to the 2002 Australian Electoral Commission’s Victorian redistribution. She closed with “We are concerned that by continuing to honour the names of people who massacred and mistreated the original inhabitants of this land, the integrity of the reconciliation process is called into question”.

Submissions were also made by other groups and individuals to the 2002 and 2010 redistributions.

The name remains. In February 2015 the AEC issued a set of guidelines for determining the names of federal electoral divisions.

The opportunity to rename this electorate returns in the last quarter of 2017 with the next AEC redistribution of Victoria.

Geoff Ellis, Wattle Bank