By Catherine Watson

CASE 1: Last summer, more than 3000 people signed petitions to the council against a daytime curfew for dogs on Bass Coast beaches.

Hundreds of dog-owners rallied on Inverloch and Coronet Bay beaches to protest at the restrictions. There were letters to newspapers, calls to radio talkback shows, and hundreds of emails to councillors and council staff, many of them threatening and abusive.

CASE 1: Last summer, more than 3000 people signed petitions to the council against a daytime curfew for dogs on Bass Coast beaches.

Hundreds of dog-owners rallied on Inverloch and Coronet Bay beaches to protest at the restrictions. There were letters to newspapers, calls to radio talkback shows, and hundreds of emails to councillors and council staff, many of them threatening and abusive.

The Herald Sun reported the ban had caused a downturn in visitors to Inverloch over the summer and homebuyers to pull out of deals. One resident claimed that retired and elderly people were “staying inside crying, saying they’re going to sell their house”.

Like most good dog stories, this one attracted state and national interest. Even the Premier, Denis Napthine, weighed in to the debate.

In February, when the council announced it would review its policy in light of the community opposition, the mayor, Neil Rankine, called for residents to work with councillors to come up with a solution to a problem that had taxed the council for 15 years. As part of the review, the council reconvened its domestic animal management advisory committee and called for nominations from the community.

After the abuse, the threats, the tears, the hundreds of emails, the hundreds who had rallied, the thousands of signatures, you might have expected a throng of people competing to get onto the committee and sort out the mess.

When nominations closed this month, just nine people had put their names forward.

CASE 2: Last year, Bass Coast Shire Council’s $65 million draft budget attracted just two submissions, and one of those was to point out a spelling mistake.

The lack of interest in the budget is hard to reconcile with the fact that four weeks ago, some 1200 Phillip Island residents and ratepayers rallied to push for the island to secede from the shire on the grounds that the island was being short-changed.

The rallying call for the meeting – “Welcome to Independence Day” – was greeted by loud cheers. But the nuts and bolts of the meeting was a financial report that claimed the island’s ratepayers provided almost half the rate revenue in 2013-14 but only received 15 per cent of the capital works.

If this is so – and the council disputes the figures – why did no one bother to read the budget and challenge the council at the time?

* * * * *

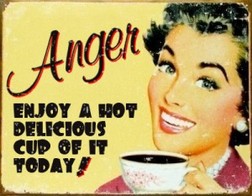

Why do so many of us prefer outrage to solutions? Probably because outrage is simple. It feels great. You know where you stand. Solving complex problems involves compromise: you have to work with people you don't even like, see other points of view, and accommodate them. It’s hard work, and kind of boring.

A former South Gippsland mayor and now a resident of Inverloch, Jenni Deane, says that while most people are blissfully unaware of the major decisions being made by councillors, they tend to latch on to comparatively minor, but tangible, issues such as dogs on beaches. There is also often a level of ignorance in very passionate campaigns. “More people are talking about it but it’s less informed.”

In last week’s Bass Coast Post, Mr Rankine wrote of the frustrations of trying to engage the community. “How do we turn around the negativity and encourage our constituents to join the discussion, to think about the future, to articulate their vision for the kind of community they want?

“The council already invites submissions on all our major policy changes, but rarely do more than a few respond. Facebook and letters to the editor provide anyone with an easy option for a quick dig at council, or perhaps to express self-interest.

“What we’re often missing is comment from those who are normally quiet, and conversations about the broader good.”

At Wednesday’s council meeting, at which the shire’s draft budget for 2014-15 was released, Cr Kimberley Brown expressed a similar frustration. In view of independence push for Phillip Island, she said, she hoped many more would take the time to go thought this year’s budget and make a submission.

On Wednesday, the council gallery was unusually full, with about three dozen Phillip Islanders there to see if the council would support an independent municipal review, an essential first step in a campaign to secede from the shire.

Veteran council watcher and Cowes resident Maurice Schinkel was disappointed, but not surprised, when most of them left after their item, which was the first on the agenda.

Apparently of no interest to the visitors were the items that followed: the shire’s 2014-15 budget, a plan to revitalise the Cowes town centre, a landscape master plan for the Scenic Estate reserve (with state government funding expected to be announced on Monday), the release of a Cowes recreation land master plan, incorporating an aquatic centre, and a draft traffic management plan for Surf Beach and Sunderland Bay.

“Some stayed for the budget,” Mr Schinkel said. “After that, it was down to we happy few, as usual.”

For him, the most important item of the night was a Crown land management review for Phillip Island’s south and north coast, which attracted little interest, even from councillors.

Mr Schinkel, who stood for the council at the 2012 election and intends to stand again, laments that most people are motivated by narrow self-interest.

He was at the torrid council meeting in Cowes last December when a large number of people travelled from Inverloch to hear councillors review the beach curfew on dogs.

“As soon as the dogs issue was over, they streamed out and stood outside whinging about how they had to walk their dog on the road.

“Meanwhile the next item on the agenda was the structure plan for Inverloch. Basically an overlay for all the land use for Inverloch. They didn’t stick around for that. It’s complete self-interest and so narrow. You can’t deal with your issue in isolation. It’s also showing a lack of respect for the councillors.”

One solution to the general apathy, he says, may be to reduce the wordiness of council agendas and reports.

He believes even some of the councillors are struggling with council documents that are over-wordy, over-complex, full of motherhood statements and saying little of substance. “Why do the councillors tolerate receiving such reports?”

So if the reports were more concise, people might read them and become better informed and less narrow?

Mr Schinkel hesitates. “Probably not,” he concedes. “It’s hard to know what would motivate them apart from self-interest.”

Like most good dog stories, this one attracted state and national interest. Even the Premier, Denis Napthine, weighed in to the debate.

In February, when the council announced it would review its policy in light of the community opposition, the mayor, Neil Rankine, called for residents to work with councillors to come up with a solution to a problem that had taxed the council for 15 years. As part of the review, the council reconvened its domestic animal management advisory committee and called for nominations from the community.

After the abuse, the threats, the tears, the hundreds of emails, the hundreds who had rallied, the thousands of signatures, you might have expected a throng of people competing to get onto the committee and sort out the mess.

When nominations closed this month, just nine people had put their names forward.

CASE 2: Last year, Bass Coast Shire Council’s $65 million draft budget attracted just two submissions, and one of those was to point out a spelling mistake.

The lack of interest in the budget is hard to reconcile with the fact that four weeks ago, some 1200 Phillip Island residents and ratepayers rallied to push for the island to secede from the shire on the grounds that the island was being short-changed.

The rallying call for the meeting – “Welcome to Independence Day” – was greeted by loud cheers. But the nuts and bolts of the meeting was a financial report that claimed the island’s ratepayers provided almost half the rate revenue in 2013-14 but only received 15 per cent of the capital works.

If this is so – and the council disputes the figures – why did no one bother to read the budget and challenge the council at the time?

* * * * *

Why do so many of us prefer outrage to solutions? Probably because outrage is simple. It feels great. You know where you stand. Solving complex problems involves compromise: you have to work with people you don't even like, see other points of view, and accommodate them. It’s hard work, and kind of boring.

A former South Gippsland mayor and now a resident of Inverloch, Jenni Deane, says that while most people are blissfully unaware of the major decisions being made by councillors, they tend to latch on to comparatively minor, but tangible, issues such as dogs on beaches. There is also often a level of ignorance in very passionate campaigns. “More people are talking about it but it’s less informed.”

In last week’s Bass Coast Post, Mr Rankine wrote of the frustrations of trying to engage the community. “How do we turn around the negativity and encourage our constituents to join the discussion, to think about the future, to articulate their vision for the kind of community they want?

“The council already invites submissions on all our major policy changes, but rarely do more than a few respond. Facebook and letters to the editor provide anyone with an easy option for a quick dig at council, or perhaps to express self-interest.

“What we’re often missing is comment from those who are normally quiet, and conversations about the broader good.”

At Wednesday’s council meeting, at which the shire’s draft budget for 2014-15 was released, Cr Kimberley Brown expressed a similar frustration. In view of independence push for Phillip Island, she said, she hoped many more would take the time to go thought this year’s budget and make a submission.

On Wednesday, the council gallery was unusually full, with about three dozen Phillip Islanders there to see if the council would support an independent municipal review, an essential first step in a campaign to secede from the shire.

Veteran council watcher and Cowes resident Maurice Schinkel was disappointed, but not surprised, when most of them left after their item, which was the first on the agenda.

Apparently of no interest to the visitors were the items that followed: the shire’s 2014-15 budget, a plan to revitalise the Cowes town centre, a landscape master plan for the Scenic Estate reserve (with state government funding expected to be announced on Monday), the release of a Cowes recreation land master plan, incorporating an aquatic centre, and a draft traffic management plan for Surf Beach and Sunderland Bay.

“Some stayed for the budget,” Mr Schinkel said. “After that, it was down to we happy few, as usual.”

For him, the most important item of the night was a Crown land management review for Phillip Island’s south and north coast, which attracted little interest, even from councillors.

Mr Schinkel, who stood for the council at the 2012 election and intends to stand again, laments that most people are motivated by narrow self-interest.

He was at the torrid council meeting in Cowes last December when a large number of people travelled from Inverloch to hear councillors review the beach curfew on dogs.

“As soon as the dogs issue was over, they streamed out and stood outside whinging about how they had to walk their dog on the road.

“Meanwhile the next item on the agenda was the structure plan for Inverloch. Basically an overlay for all the land use for Inverloch. They didn’t stick around for that. It’s complete self-interest and so narrow. You can’t deal with your issue in isolation. It’s also showing a lack of respect for the councillors.”

One solution to the general apathy, he says, may be to reduce the wordiness of council agendas and reports.

He believes even some of the councillors are struggling with council documents that are over-wordy, over-complex, full of motherhood statements and saying little of substance. “Why do the councillors tolerate receiving such reports?”

So if the reports were more concise, people might read them and become better informed and less narrow?

Mr Schinkel hesitates. “Probably not,” he concedes. “It’s hard to know what would motivate them apart from self-interest.”