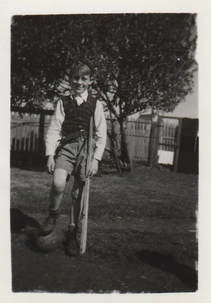

With the quarter-acre block a threatened species, Terri Allen celebrates the big backyard of her childhood.

By Terri Allen

WONTHAGGI has changed. There can be no better measure than to look at the average yard. Today’s new estates have smaller blocks with McMansions, narrower nature strips and roads, pocket-handkerchief yards that are concreted, pebbled and yucca-ed. Evidence of children is usually a jumble of lurid plastic toys and the netted trampoline.

What of the old quarter-acre block? Many are subdivided into two or three units. Cars abound on nature strips and lawns. There is little pride in gardening; kikuyu and blackberries are rife. Just walk down the back lanes to see flapping tin fences, piles of grass clippings, rubbish, dead cars, clogged drains.

Compare this with the house blocks of the `40s, `50s, `60s. There was an expanse of lawn with a clothesline, prolific vegetable gardens, fruit trees (remembering the miner’s lifeline during strikes – have a well-stocked larder, vegetable garden, fruit trees, chooks, access to a cow, skills to acquire rabbits, fish, mushrooms, blackberries), a coal heap, a wood stack, a donkey boiler for hot water, a separate wash house (at first with copper and troughs), a toolshed/garage, and shady trees. Admittedly there were open drains, a pan toilet on the lane and red-metal roads, but there was a close community and plenty of room to play. The mine whistle dominated life, signalling when to rise, get ready for school or lunch, and come in at night.

Ours was a typical quarter-acre block on an unmade road with a back lane for the nightcart man to access the dunny (beautifully draped with Dolichos pea). The chooks and ducks resided at the back, the dog midway. A huge boobialla gave privacy and shade and was great to climb. In the wooden garage and its lean-to, children could create wooden models, including billy-carts. The coal heap was under the remnant messmate, from which the swing hung, the wood shed next door. The side fence still had scrub sheoak and swamp tea-tree along its length. Pride of place was given to the rotary clothesline, a replacement for the old prop clothes-line.

Our front yard harboured the house, detached wash-house, shed for the donkey boiler, sheltered verandah, neat flower beds, the whole securely fenced. Trees provided shade and shelter. The front door was for strangers; everyone else came into the house via the back door and porch; here the breadman collected the tokens, Dommy Dobson came for the co-op order, wet and muddy shoes and coats were deposited, schoolbags were stored, and boots and shoes polished every day.

The yard provided endless scope for games, balanced walking along the front fence, ball games using the fence as the “net”, skating on pieces of watermelon skin on the concrete paths, running through the sprinkler, swinging on the rotary clothes line, climbing trees, building cubbies and shops, collecting insects, hidey, chasey, shangeye practice, jam-tin telephones, stilt-walking, marbles, hopscotch, rounders, cricket (over the fence was six and out).

The local environs were an extension of the yard, common ground on which to mix with the neighbourhood children. We had a sandhill, claypits, vacant blocks, bush, a common, drains, footpaths. Our open drains were a source of pleasure: skating over the icy bridges in winter, hiding in the culverts, floating toy boats , tadpoling. Many of these gutters were thickly fringed with swamp paperbark, so sticks for huts were plentiful. Forced to drag little brother along? Penetrate the scrub, jump the gutter, through more scrub – oh bother, he forgot to jump, fell in again! Oh well, there he goes off home, bawling. Can’t seem to get the gift of gutter-jumping!

A nearby hill provided tracks for chasey and trip wires, sandy patches for cooking bandicooted spuds. A vacant block was perfect for building a communal bonfire. The Saturday arvo flicks fuelled our imagination for games: cops and robbers, pirates, cowboys and Indians, outer space adventure. Cricket and footy were played on the streets or the “flat” (now oval); here, too, we flew kites.

The neighbour kids played and squabbled, brokered deals, swapped comics and swap-cards, shared games and play-things, combined to build and make toys (billycarts, kites, swords, stilts, bows and arrows). They improved their social and communication skills, learned teamwork, knew their community and environment intimately, shared ideas, practised being leader and follower, traded treasures and looked after each other.

Their horizons expanded to include new ventures further from home: blackberrying, mushrooming, fishing, rabbiting, trekking to the beach, visiting new patches of bush.

Those were the days. And those were the yards.

COMMENTS

July 11, 2016

I greatly enjoyed Terri Allen's descriptions of backyards past. I well recall the layouts, games and freedoms she writes of. Every back yard was the same but different. I remember that each of the yards I visited or played in had some special attraction that made it special in some way.

I loved one grandmother's yard because of the jungle of bamboo in one corner, perfect for playing all sorts of games in. My other grandmother had a large overgrown aloe garden patch that housed the most wonderful colony of jackie lizards, a great attraction for little boys.

Other yards had different pleasures and attractions but they were all wonderful.

A very enjoyable story and stirring of memories.

Kit Sleeman

WONTHAGGI has changed. There can be no better measure than to look at the average yard. Today’s new estates have smaller blocks with McMansions, narrower nature strips and roads, pocket-handkerchief yards that are concreted, pebbled and yucca-ed. Evidence of children is usually a jumble of lurid plastic toys and the netted trampoline.

What of the old quarter-acre block? Many are subdivided into two or three units. Cars abound on nature strips and lawns. There is little pride in gardening; kikuyu and blackberries are rife. Just walk down the back lanes to see flapping tin fences, piles of grass clippings, rubbish, dead cars, clogged drains.

Compare this with the house blocks of the `40s, `50s, `60s. There was an expanse of lawn with a clothesline, prolific vegetable gardens, fruit trees (remembering the miner’s lifeline during strikes – have a well-stocked larder, vegetable garden, fruit trees, chooks, access to a cow, skills to acquire rabbits, fish, mushrooms, blackberries), a coal heap, a wood stack, a donkey boiler for hot water, a separate wash house (at first with copper and troughs), a toolshed/garage, and shady trees. Admittedly there were open drains, a pan toilet on the lane and red-metal roads, but there was a close community and plenty of room to play. The mine whistle dominated life, signalling when to rise, get ready for school or lunch, and come in at night.

Ours was a typical quarter-acre block on an unmade road with a back lane for the nightcart man to access the dunny (beautifully draped with Dolichos pea). The chooks and ducks resided at the back, the dog midway. A huge boobialla gave privacy and shade and was great to climb. In the wooden garage and its lean-to, children could create wooden models, including billy-carts. The coal heap was under the remnant messmate, from which the swing hung, the wood shed next door. The side fence still had scrub sheoak and swamp tea-tree along its length. Pride of place was given to the rotary clothesline, a replacement for the old prop clothes-line.

Our front yard harboured the house, detached wash-house, shed for the donkey boiler, sheltered verandah, neat flower beds, the whole securely fenced. Trees provided shade and shelter. The front door was for strangers; everyone else came into the house via the back door and porch; here the breadman collected the tokens, Dommy Dobson came for the co-op order, wet and muddy shoes and coats were deposited, schoolbags were stored, and boots and shoes polished every day.

The yard provided endless scope for games, balanced walking along the front fence, ball games using the fence as the “net”, skating on pieces of watermelon skin on the concrete paths, running through the sprinkler, swinging on the rotary clothes line, climbing trees, building cubbies and shops, collecting insects, hidey, chasey, shangeye practice, jam-tin telephones, stilt-walking, marbles, hopscotch, rounders, cricket (over the fence was six and out).

The local environs were an extension of the yard, common ground on which to mix with the neighbourhood children. We had a sandhill, claypits, vacant blocks, bush, a common, drains, footpaths. Our open drains were a source of pleasure: skating over the icy bridges in winter, hiding in the culverts, floating toy boats , tadpoling. Many of these gutters were thickly fringed with swamp paperbark, so sticks for huts were plentiful. Forced to drag little brother along? Penetrate the scrub, jump the gutter, through more scrub – oh bother, he forgot to jump, fell in again! Oh well, there he goes off home, bawling. Can’t seem to get the gift of gutter-jumping!

A nearby hill provided tracks for chasey and trip wires, sandy patches for cooking bandicooted spuds. A vacant block was perfect for building a communal bonfire. The Saturday arvo flicks fuelled our imagination for games: cops and robbers, pirates, cowboys and Indians, outer space adventure. Cricket and footy were played on the streets or the “flat” (now oval); here, too, we flew kites.

The neighbour kids played and squabbled, brokered deals, swapped comics and swap-cards, shared games and play-things, combined to build and make toys (billycarts, kites, swords, stilts, bows and arrows). They improved their social and communication skills, learned teamwork, knew their community and environment intimately, shared ideas, practised being leader and follower, traded treasures and looked after each other.

Their horizons expanded to include new ventures further from home: blackberrying, mushrooming, fishing, rabbiting, trekking to the beach, visiting new patches of bush.

Those were the days. And those were the yards.

COMMENTS

July 11, 2016

I greatly enjoyed Terri Allen's descriptions of backyards past. I well recall the layouts, games and freedoms she writes of. Every back yard was the same but different. I remember that each of the yards I visited or played in had some special attraction that made it special in some way.

I loved one grandmother's yard because of the jungle of bamboo in one corner, perfect for playing all sorts of games in. My other grandmother had a large overgrown aloe garden patch that housed the most wonderful colony of jackie lizards, a great attraction for little boys.

Other yards had different pleasures and attractions but they were all wonderful.

A very enjoyable story and stirring of memories.

Kit Sleeman