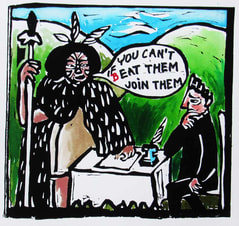

Cartoon: Natasha Williams-Novak

Cartoon: Natasha Williams-Novak On a visit to New Zealand, Tim Shannon finds a country that has embraced the Maori culture of sharing.

By Tim Shannon

MOST of us are travellers, descended one way or another from some travelling tribe. Nowadays, the more privileged of us no longer go by foot, we travel by a machine of some kind, a car, bus, train, tram, or maybe a motorbike or pedal bike. The seriously privileged travel in cruise liners across the oceans, or dream liners through the skies. Ships and planes are the Trojan Horses of modern travellers, disgorging thousands of foreigners into the distant cities of their desires.

Nearly all of us are smart phone travellers. This travellers’ companion gives us access to information about foreign places that history’s great invaders, explorers and spies could never have imagined. Now we can travel the world free from language barriers, navigating our way into the tiniest crevices in the remotest, largest and most complicated of places.

Some of us are inveterate tourists, feeding our desires and imaginations, staving off our boredom, travelling, travelling, and travelling. There are virtual bridges of dream liners in the skies at every hour of the day moving us to and from places all around the world. On the seas there are floating bridges of cruise liners doing just the same. These bridges transport us to destinations which we devour like termites, consuming their novelty before moving on, leaving the carcass behind.

In a foreigners’ land, armed with Satnav, Google Maps, Google Earth, Trip Advisor, and good old Safari, there is no need to talk with local folk. We invaders arrive fully informed, ready for a perfectly planned experience, which we have reviewed and tested by checking with the opinions of thousands of other anonymous travellers who preceded us. Our hosts know less about their home than we do, and our expectations are set.

So prepared, my wife and I recently flew to New Zealand for a two-week road trip of the North Island. First settled by adventurous island explorers of the Pacific some 700 years ago, and then discovered by Europeans some 500 years later, this dramatic volcanic, craggy outcrop in the South Pacific is a not a familiar setting for most travellers.

They say that the culture of island populations is a deep reflection of how they were first settled, peacefully or violently. The limited pockets of habitable land around New Zealand’s rugged coastline have provided places for communities which are separate but joined, inhabited but shared. Somehow, the original island settlers developed a strong culture throughout the land which is based on the notion of prospering by sharing.

The first Europeans to arrive were sailors and adventurers, whalers and traders, looking for a safe harbour on the other side of the world. They arrived in the Bay of Islands, the same place where the original Islanders settled. This outpost far from home was an escape from the conformity of law and religion, it was a haven for non-conformers, and adventuring opportunists.

Unlike the sorry tales of European settlement in America and Australia, the strength of the indigenous culture and community proved to be a match for the European colonials. The Treaty of Waitangi signed in 1840 between the British Crown and some 540 Maori chiefs is lasting testament to this, and the Maori culture of sharing is its legacy.

Inhabiting a raw and dramatic volcanic atoll is not for the faint hearted. There are threats of earthquakes, volcanoes erupting, and tsunamis. Life is adventurous, close to the elements, the ocean, the mountains and forests. There is a tricky way of making do, a delicate but intense existence. Here is the beautiful, the primitive, the peaceful, the wild, the inspiring and the frightening. There is no need for pretence or sophistry, a daunting rawness sits beside boundless verdant beauty. Travelling in this place, looking for the familiar becomes tiring, and an appreciation of the random slowly takes over. There are no norms, just a perfect non-conforming milieu. The cauldron of the Maoris and the Europeans has conjured a spectacle of opposites which has thrived through sharing.

On our second last day, walking around Auckland’s city streets, annoyed that we could not find the signs that Google said would be there, bemused by the jumble of unkempt urbanity interspersed with jewels of delight, intrigued by the disregard for fashion norms and exhibitions of body art and the vast array of skin colours from the whitest of white to the blackest of black, we sometimes stumbled into attractive mall like places where we dodged the random cars that came from nowhere. Here we found the sign which read, “This is a Shared Space”. Without blinking, we sent our comment to TripAdvisor, “New Zealand, highly recommended, come and see what is possible if you are willing to share”.

MOST of us are travellers, descended one way or another from some travelling tribe. Nowadays, the more privileged of us no longer go by foot, we travel by a machine of some kind, a car, bus, train, tram, or maybe a motorbike or pedal bike. The seriously privileged travel in cruise liners across the oceans, or dream liners through the skies. Ships and planes are the Trojan Horses of modern travellers, disgorging thousands of foreigners into the distant cities of their desires.

Nearly all of us are smart phone travellers. This travellers’ companion gives us access to information about foreign places that history’s great invaders, explorers and spies could never have imagined. Now we can travel the world free from language barriers, navigating our way into the tiniest crevices in the remotest, largest and most complicated of places.

Some of us are inveterate tourists, feeding our desires and imaginations, staving off our boredom, travelling, travelling, and travelling. There are virtual bridges of dream liners in the skies at every hour of the day moving us to and from places all around the world. On the seas there are floating bridges of cruise liners doing just the same. These bridges transport us to destinations which we devour like termites, consuming their novelty before moving on, leaving the carcass behind.

In a foreigners’ land, armed with Satnav, Google Maps, Google Earth, Trip Advisor, and good old Safari, there is no need to talk with local folk. We invaders arrive fully informed, ready for a perfectly planned experience, which we have reviewed and tested by checking with the opinions of thousands of other anonymous travellers who preceded us. Our hosts know less about their home than we do, and our expectations are set.

So prepared, my wife and I recently flew to New Zealand for a two-week road trip of the North Island. First settled by adventurous island explorers of the Pacific some 700 years ago, and then discovered by Europeans some 500 years later, this dramatic volcanic, craggy outcrop in the South Pacific is a not a familiar setting for most travellers.

They say that the culture of island populations is a deep reflection of how they were first settled, peacefully or violently. The limited pockets of habitable land around New Zealand’s rugged coastline have provided places for communities which are separate but joined, inhabited but shared. Somehow, the original island settlers developed a strong culture throughout the land which is based on the notion of prospering by sharing.

The first Europeans to arrive were sailors and adventurers, whalers and traders, looking for a safe harbour on the other side of the world. They arrived in the Bay of Islands, the same place where the original Islanders settled. This outpost far from home was an escape from the conformity of law and religion, it was a haven for non-conformers, and adventuring opportunists.

Unlike the sorry tales of European settlement in America and Australia, the strength of the indigenous culture and community proved to be a match for the European colonials. The Treaty of Waitangi signed in 1840 between the British Crown and some 540 Maori chiefs is lasting testament to this, and the Maori culture of sharing is its legacy.

Inhabiting a raw and dramatic volcanic atoll is not for the faint hearted. There are threats of earthquakes, volcanoes erupting, and tsunamis. Life is adventurous, close to the elements, the ocean, the mountains and forests. There is a tricky way of making do, a delicate but intense existence. Here is the beautiful, the primitive, the peaceful, the wild, the inspiring and the frightening. There is no need for pretence or sophistry, a daunting rawness sits beside boundless verdant beauty. Travelling in this place, looking for the familiar becomes tiring, and an appreciation of the random slowly takes over. There are no norms, just a perfect non-conforming milieu. The cauldron of the Maoris and the Europeans has conjured a spectacle of opposites which has thrived through sharing.

On our second last day, walking around Auckland’s city streets, annoyed that we could not find the signs that Google said would be there, bemused by the jumble of unkempt urbanity interspersed with jewels of delight, intrigued by the disregard for fashion norms and exhibitions of body art and the vast array of skin colours from the whitest of white to the blackest of black, we sometimes stumbled into attractive mall like places where we dodged the random cars that came from nowhere. Here we found the sign which read, “This is a Shared Space”. Without blinking, we sent our comment to TripAdvisor, “New Zealand, highly recommended, come and see what is possible if you are willing to share”.