Essays on encounters with Firmness and Commodity, by Tim Shannon, with thanks to Vitruvius

“Firmitus, utilitus, venustas.”

Vitruvius Pollio, 1st Century BC.

Vitruvius Pollio, 1st Century BC.

1: Doors

SHOULD you try to hang a door it will earn your respect. There is the right way and the wrong way for door hanging. Get it wrong and that door will be a curse forever. Doors are pervasive, taken for granted, always there when needed, and silent companions in everyday life. Some doors are more important than others, but we are servants to each of them, passing through them all our life. Our daily comings and goings, our rituals, our society, and our language are all richer thanks to the door.

At first glance the door is a simple thing, but what it does is remarkable. The first shelters such as caves, hutches, tents and the like had a door which was the only way in and out. It provided safety, ownership, privacy, identity, light, air, a place for thinking and for meetings and conversations. This entrance unites the indoors with the outdoors, and it connects a group of shelters to make a community.

Along the way life has become sophisticated and the door has become more important. It has meaning as well as purpose. A door tells of tribe, family, rank, prosperity, religion and profession. It might be swung, closed, open, ajar, slammed, thrown, bolted, secured, or burst. A door is the place for grand entries, quick exits, welcomes and farewells. For some the door is always open; for others it is closed; or for others, their doors are never closed.

A door is a stage for human behaviour. Meet me at the door, come to the door, step up to the door, come in by the door, leave by the door. A place for a chat, a glance, a rest, reading mail, a chair, flowers in pots, leaving a message, a sleeping dog or cat. The door needs generosity for it to accommodate our arrivals and departures.

Doors have many guises. My family built a new house and the front door was swung the wrong way, it stayed like that and annoyed us every day. Twenty years later it is a welcome inconvenience, like an old dog that is sad to see you leave and pleased to see you home. Another time we painted the front door to our beach house with automotive paint, and that shiny door is a treat. These doors nurture pleasure.

The sculpted bronze doors of the Duomo in Pisa are a work of art that has attracted attention for centuries. The relief is worn and shining where countless inquisitive hands have reached to touch it. These doors nurture faith. In the Forbidden City in Beijing, the Emperor sits at the centre of the Chinese cosmos. The grand procession from outside to the Emperor’s throne is made of many doorways in ascending importance. These doors nurture power.

Banks have doors that feel safe. Shops have doors that make you welcome. Hospitals have doors you can trust. Law courts have doors that are important. Prisons have doors that are frightening. Schools have doors that are welcoming. Universities have doors that ask for respect. Museums have doors that are mysterious. Theatres have doors that are fun.

Doors speak to us through the materials they are made of, their size and location, the floor they sit on, the rooms they connect, and their touch which is the evidence of the craftsmanship in their making. In addition to connecting communities, doors provide these communities with meaning and values, they offer memories of the past and they influence the present and the future.

Perhaps the most important room in Australia is the Number One Court Room in the High Court in Canberra, where the Court of Appeal sits to judge on matters that shape the nation. This public room is bathed in daylight, steeped in forensic character, comforting, and uncannily Australian. The court room doors are made of glass and silver, and their craftsmanship is the work of artists. The sculpted handles invite your touch, your gaze is filtered by designs etched on the glass, and your senses are alert as you pass though the most important doors in the land.

Our belief in spiritual things is as old as doors, the miracles of appearing and disappearing at whim and passing through time and space are ancient legends. Secret doors and passageways and illusionists tricks are examples of this fascination. Automatic doors and air curtains make it possible for us to walk through walls. The telephone makes it possible for our voices to travel freely, and photography makes it possible for our images to do the same. The mobile phone makes it possible for our likeness to appear anywhere in the world at any time, and for us to receive visitors from anywhere at any time at any location. This is a world without doors.

Over time our communities gathered in cities, and while some of these have withered, many have grown thanks in part to technological change. Cities present us with the challenge of size. When the familiar gets bigger, its identity changes, sometimes becoming altogether new, and the meaning of our familiar things falls victim to this unexpected change. In this evolution of our built and virtual worlds, we should always question who is the master and who is the servant. Respect for what is public and private is a proven master, and the door is a friendly reminder of how a good servant can enrich our shifting between the two.

COMMENTS

August 14, 2015

I enjoyed this article for its originality. So well written, it focuses the reader’s attention on object we take for granted. It is a meditation: profound and philosophical.

Thanks again to the POST for a good read!

Heather Murray Tobias, Wonthaggi

At first glance the door is a simple thing, but what it does is remarkable. The first shelters such as caves, hutches, tents and the like had a door which was the only way in and out. It provided safety, ownership, privacy, identity, light, air, a place for thinking and for meetings and conversations. This entrance unites the indoors with the outdoors, and it connects a group of shelters to make a community.

Along the way life has become sophisticated and the door has become more important. It has meaning as well as purpose. A door tells of tribe, family, rank, prosperity, religion and profession. It might be swung, closed, open, ajar, slammed, thrown, bolted, secured, or burst. A door is the place for grand entries, quick exits, welcomes and farewells. For some the door is always open; for others it is closed; or for others, their doors are never closed.

A door is a stage for human behaviour. Meet me at the door, come to the door, step up to the door, come in by the door, leave by the door. A place for a chat, a glance, a rest, reading mail, a chair, flowers in pots, leaving a message, a sleeping dog or cat. The door needs generosity for it to accommodate our arrivals and departures.

Doors have many guises. My family built a new house and the front door was swung the wrong way, it stayed like that and annoyed us every day. Twenty years later it is a welcome inconvenience, like an old dog that is sad to see you leave and pleased to see you home. Another time we painted the front door to our beach house with automotive paint, and that shiny door is a treat. These doors nurture pleasure.

The sculpted bronze doors of the Duomo in Pisa are a work of art that has attracted attention for centuries. The relief is worn and shining where countless inquisitive hands have reached to touch it. These doors nurture faith. In the Forbidden City in Beijing, the Emperor sits at the centre of the Chinese cosmos. The grand procession from outside to the Emperor’s throne is made of many doorways in ascending importance. These doors nurture power.

Banks have doors that feel safe. Shops have doors that make you welcome. Hospitals have doors you can trust. Law courts have doors that are important. Prisons have doors that are frightening. Schools have doors that are welcoming. Universities have doors that ask for respect. Museums have doors that are mysterious. Theatres have doors that are fun.

Doors speak to us through the materials they are made of, their size and location, the floor they sit on, the rooms they connect, and their touch which is the evidence of the craftsmanship in their making. In addition to connecting communities, doors provide these communities with meaning and values, they offer memories of the past and they influence the present and the future.

Perhaps the most important room in Australia is the Number One Court Room in the High Court in Canberra, where the Court of Appeal sits to judge on matters that shape the nation. This public room is bathed in daylight, steeped in forensic character, comforting, and uncannily Australian. The court room doors are made of glass and silver, and their craftsmanship is the work of artists. The sculpted handles invite your touch, your gaze is filtered by designs etched on the glass, and your senses are alert as you pass though the most important doors in the land.

Our belief in spiritual things is as old as doors, the miracles of appearing and disappearing at whim and passing through time and space are ancient legends. Secret doors and passageways and illusionists tricks are examples of this fascination. Automatic doors and air curtains make it possible for us to walk through walls. The telephone makes it possible for our voices to travel freely, and photography makes it possible for our images to do the same. The mobile phone makes it possible for our likeness to appear anywhere in the world at any time, and for us to receive visitors from anywhere at any time at any location. This is a world without doors.

Over time our communities gathered in cities, and while some of these have withered, many have grown thanks in part to technological change. Cities present us with the challenge of size. When the familiar gets bigger, its identity changes, sometimes becoming altogether new, and the meaning of our familiar things falls victim to this unexpected change. In this evolution of our built and virtual worlds, we should always question who is the master and who is the servant. Respect for what is public and private is a proven master, and the door is a friendly reminder of how a good servant can enrich our shifting between the two.

COMMENTS

August 14, 2015

I enjoyed this article for its originality. So well written, it focuses the reader’s attention on object we take for granted. It is a meditation: profound and philosophical.

Thanks again to the POST for a good read!

Heather Murray Tobias, Wonthaggi

Part 2: Windows

WHAT sort of window would you like? There is a feast to choose from: single sash, double sash, double hung sash, awning, sliding, hopper, casement, louvered, fixed, framed or frameless. And, what sort of glass would you prefer: clear, diffused, wired, toughened, laminated, double glazed, or triple glazed, tinted, mirrored, film protected, or special E coated? Would you like insect screens, security locks, winders, friction stays, curtains, blinds internal or external, shutters internal or external? Which frames would suit: timber natural or painted, steel, aluminium anodised, natural or powder coated, or plastic? Would you like a window that is very small or perhaps the size of an entire wall?

There was a time when one window in a room was luxury, and having it fitted with small panes of clear hand blown glass was opulence. That window worked hard; it provided the room with light, air, sounds and smells, sunshine, moonlight, and view. In a room it enjoyed a partnership with the door, allowing light and outlook when the door was closed safely tight. The placement of these partners shaped the way the room was occupied and used. One wall for the door, one wall for the window, and two blank walls. Together they made the stage where generations of life would play out.

A good window gives consideration to admitting light, permitting view, and supporting our needs and behaviour. Georgian windows held each precious pane of glass in patterns that united the parts into a whole. They had sculpted frames and architraves which made the most of each ray of light entering the room. They had a generous depth and a friendly size which invited attention and use, and they made a beautiful connection between inside and outside as they captured and framed the view. The preciousness of the glass, dependency on daylight, and the limitations of size all conspired to give the room a valued friend.

A good window permits and encourages its use for many things as it brings our rooms to life. It might be a seat, a place for a flower box, a shelf for treasures or ripening fruit, a lookout for a child, a sleeping place for a cat, somewhere for the bird cage, a place to listen from or share a secret, a place to feel the breeze, a place to read, somewhere to snooze, a lookout for the return of family and friends, somewhere to sit in winter sunshine, or to see the sun rise and set and the clouds and moon pass by.

Having entered our rooms, windows changed the appearance of our buildings. As they flourished a new word – “fenestration” – came to describe their presence. Windows need an opening to be made in a wall, which will vary according to what the wall is built of, whether brush, wattle and daub, rocks, timber, stones, brick, concrete, or steel. There is a trick in spanning the top of this opening while maintaining the strength of the punctured wall, and this has accounted for changes to the appearance of buildings for thousands of years. Thanks to the flat tops and round and pointed arches of windows, buildings have endured being primitive, vernacular, crafted, Egyptian, Greek, Roman, middle eastern, oriental, classical, religious and modern, all with numerous revisions and revivals along the way.

Windows help buildings to explain their purpose. Day and night, their transparency allows life inside to be revealed to onlookers and passers-by. Their size and arrangement suggest the diversity and importance of the activities they are serving. They bring familiarity and meaning to the buildings that shape our communities, they make it possible to recognise a house, a school, a shop, a hospital, a bank, a hotel, a factory and a gaol.

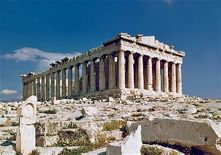

In France there is a monastery called Sainte Marie de la Tourette for an order of monks who have taken a vow of silence. It was designed in 1960 by the famous architect Le Corbusier who was an admirer of Phidias the architect of the Parthenon, and who believed that “architecture is the magnificent play of light on volumes in space”. La Tourette, a speechless place, is a symphony of windows which respond to use, views within and without, light, sun, colour, privacy, community, ritual and the spiritual. It continues to be a place of pilgrimage for people from around the world.

In the past, choice was limited and necessity resulted in inventive diversity, but in the developed world choices are abundant. A single window was once a luxury. Today it is possible to cover an entire building with a curtain of windows. What irony in this time of abundance to find there is a tribal desire to be the same, and the window of popular choice is endless glass ribbons reaching from floor to ceiling stacked monotonously high one upon the other. Now the need for identity is satisfied by shaping our anonymous buildings in meaningless ways that try to amuse and surprise us, drawing on the surreal for inspiration. If buildings are the record of cultural history, what stories will these buildings write?

COMMENTS

September 9, 2015

Another enjoyable and entertaining edition, thanks. After spending the majority of my working life involved in the manufacture and processing of float glass, I loved Tim Shannon's article.

From the first "...small panes of clear hand blown glass was opulence", glass has transformed the way we live and interact with the environment, it enables architects and many others to create things to improve and enhance our lives.

The glass Tim refers to as cladding monotonous and anonymous buildings in modern architecture is a marvel of human ingenuity, perseverance and ability, a creation that, for most people, has failed if we become aware of it! The "Emperors New Clothes" from my childhood is a beautiful example of what we expect from this humble product.

How can something we are not meant to see or be aware of defend itself from the eloquence and ability of those who rely on it to create their own paths in life?

Tony Hughes

There was a time when one window in a room was luxury, and having it fitted with small panes of clear hand blown glass was opulence. That window worked hard; it provided the room with light, air, sounds and smells, sunshine, moonlight, and view. In a room it enjoyed a partnership with the door, allowing light and outlook when the door was closed safely tight. The placement of these partners shaped the way the room was occupied and used. One wall for the door, one wall for the window, and two blank walls. Together they made the stage where generations of life would play out.

A good window gives consideration to admitting light, permitting view, and supporting our needs and behaviour. Georgian windows held each precious pane of glass in patterns that united the parts into a whole. They had sculpted frames and architraves which made the most of each ray of light entering the room. They had a generous depth and a friendly size which invited attention and use, and they made a beautiful connection between inside and outside as they captured and framed the view. The preciousness of the glass, dependency on daylight, and the limitations of size all conspired to give the room a valued friend.

A good window permits and encourages its use for many things as it brings our rooms to life. It might be a seat, a place for a flower box, a shelf for treasures or ripening fruit, a lookout for a child, a sleeping place for a cat, somewhere for the bird cage, a place to listen from or share a secret, a place to feel the breeze, a place to read, somewhere to snooze, a lookout for the return of family and friends, somewhere to sit in winter sunshine, or to see the sun rise and set and the clouds and moon pass by.

Having entered our rooms, windows changed the appearance of our buildings. As they flourished a new word – “fenestration” – came to describe their presence. Windows need an opening to be made in a wall, which will vary according to what the wall is built of, whether brush, wattle and daub, rocks, timber, stones, brick, concrete, or steel. There is a trick in spanning the top of this opening while maintaining the strength of the punctured wall, and this has accounted for changes to the appearance of buildings for thousands of years. Thanks to the flat tops and round and pointed arches of windows, buildings have endured being primitive, vernacular, crafted, Egyptian, Greek, Roman, middle eastern, oriental, classical, religious and modern, all with numerous revisions and revivals along the way.

Windows help buildings to explain their purpose. Day and night, their transparency allows life inside to be revealed to onlookers and passers-by. Their size and arrangement suggest the diversity and importance of the activities they are serving. They bring familiarity and meaning to the buildings that shape our communities, they make it possible to recognise a house, a school, a shop, a hospital, a bank, a hotel, a factory and a gaol.

In France there is a monastery called Sainte Marie de la Tourette for an order of monks who have taken a vow of silence. It was designed in 1960 by the famous architect Le Corbusier who was an admirer of Phidias the architect of the Parthenon, and who believed that “architecture is the magnificent play of light on volumes in space”. La Tourette, a speechless place, is a symphony of windows which respond to use, views within and without, light, sun, colour, privacy, community, ritual and the spiritual. It continues to be a place of pilgrimage for people from around the world.

In the past, choice was limited and necessity resulted in inventive diversity, but in the developed world choices are abundant. A single window was once a luxury. Today it is possible to cover an entire building with a curtain of windows. What irony in this time of abundance to find there is a tribal desire to be the same, and the window of popular choice is endless glass ribbons reaching from floor to ceiling stacked monotonously high one upon the other. Now the need for identity is satisfied by shaping our anonymous buildings in meaningless ways that try to amuse and surprise us, drawing on the surreal for inspiration. If buildings are the record of cultural history, what stories will these buildings write?

COMMENTS

September 9, 2015

Another enjoyable and entertaining edition, thanks. After spending the majority of my working life involved in the manufacture and processing of float glass, I loved Tim Shannon's article.

From the first "...small panes of clear hand blown glass was opulence", glass has transformed the way we live and interact with the environment, it enables architects and many others to create things to improve and enhance our lives.

The glass Tim refers to as cladding monotonous and anonymous buildings in modern architecture is a marvel of human ingenuity, perseverance and ability, a creation that, for most people, has failed if we become aware of it! The "Emperors New Clothes" from my childhood is a beautiful example of what we expect from this humble product.

How can something we are not meant to see or be aware of defend itself from the eloquence and ability of those who rely on it to create their own paths in life?

Tony Hughes

Part 3: Passages

I LIVE in a house where downstairs has a long passage connecting the front entrance with stairs going up, a garage, a study, bedrooms, a bathroom, a laundry, a side garden, a studio, and a rear courtyard. That passage brings the house to life; it keeps the family together and apart. Children’s games running and hiding, slamming bedroom doors, late night conversations with laughter and tears, putting out the pets, bringing in the washing, going out to the garden, the quiet of night and the sounds of early morning.

Should you be interested in the delight of passages, on crossing the Australian continent, about half way from any direction, four remarkable places demand attention.

Uluru, the great red rock, important for indigenous men, claims its place in the centre. The passage around this giant is a wonder, a winding vista from place to place, the sun providing clues to time and place, with the brooding rock always at your side.

Kings Canyon is Uluru’s opposite, an enormous gorge cut into the earth. The passage around its rim is a procession of experiences of an ancient grandeur, glimpses ahead feed curiosity, but nothing prepares you for the finale of a water hole perched high on the edge of a sheer rock face.

Kata Juta is Uluru’s feminine companion, a place of significance for indigenous women. An enclosure of red granite outcrops worn round with time, a gentle place to be in while exploring its many secrets, feeling calm and safe, sensing familiar connections.

Palm Valley requires effort. By rocky road and then by foot, the passage winds and descends to the valley’s treasure waiting at the journey’s end. The surprising discovery of a tropical garden in the desert, complete with palms and weathered rocks as old as dinosaurs. Through thousands of years of weathering these ancient survivors have gently descended from the heights of the Himalayas.

Nature provides a variety of passages in deserts, and forests, mountains, plains, and along rivers and beaches, and they are places of enriching experience. Lives have become entwined around them through ritual, spiritual belief, and the necessity of survival. As shelters and settlements evolved they developed their own passages, reflecting and supporting the patterns of life, allowing us to move safely from place to place.

The Street, like Uluru, makes a passage that joins experiences in a progression. The Promenade, like King’s Canyon, offers a flamboyant passage that surprises and delights. The Cloistered Courtyard, like Kata Juta, provides an enclosed passage offering safety and peace, a place for contemplation. The Look Out, like Palm Valley, is a destination whose passage takes us to a very special place. These are the friends of communal life. Should you be lucky enough to visit Venice, you would enjoy a symphony of passages large and small, magnificent and plain, that unite to tell the story of a City.

These natural and organic passages have enriched our lives; we have been free to use them as some might play a musical instrument. They have invited interpretation and adaptation, and with time, we have learnt how to use the passage to create effect, to delight us while satisfying our needs. This is how cathedrals, hospitals, schools, universities, museums, law courts, and airports can be different buildings with their individual experiences. The art gallery, perhaps the simplest example, is a single passage that invites the enjoyment of art, while the hospital has many passages separating and joining rooms devoted to our care.

Neighbourhoods, towns, cities and nations are known by their famous streets and squares. London, New York and Paris are branded by Trafalgar Square, 5th Avenue, and the Champs Elysees, while Milan is famous for The Galleria. China and Russia are the homes of Tiananmen Square and Red Square. We recognise where we live by the name of a street, we find our way through cities all over the world by navigating passages that are familiar to us all, and the more delightful ones draw us like moths to the light.

For our amusement, the garden maze is an object to enjoy at a distance and a passage of spaces to explore, while the American sculptor Richard Serra arranges great curving steel plates to create powerful sculpted passageways to be experienced within and without. The experience of the passage has become an art form, and the passage itself has become an object of delight.

This is cause for celebration: our reliable old servant, the passage, has risen to lofty heights. There is a deep satisfaction in finding that our everyday behaviour can be a source of pleasure, and expressed as a universal art. Anthropologists tell us our survival depends on being able to pass safely through the stages of life. Little wonder that around the world the passage has become so treasured.

Should you be interested in the delight of passages, on crossing the Australian continent, about half way from any direction, four remarkable places demand attention.

Uluru, the great red rock, important for indigenous men, claims its place in the centre. The passage around this giant is a wonder, a winding vista from place to place, the sun providing clues to time and place, with the brooding rock always at your side.

Kings Canyon is Uluru’s opposite, an enormous gorge cut into the earth. The passage around its rim is a procession of experiences of an ancient grandeur, glimpses ahead feed curiosity, but nothing prepares you for the finale of a water hole perched high on the edge of a sheer rock face.

Kata Juta is Uluru’s feminine companion, a place of significance for indigenous women. An enclosure of red granite outcrops worn round with time, a gentle place to be in while exploring its many secrets, feeling calm and safe, sensing familiar connections.

Palm Valley requires effort. By rocky road and then by foot, the passage winds and descends to the valley’s treasure waiting at the journey’s end. The surprising discovery of a tropical garden in the desert, complete with palms and weathered rocks as old as dinosaurs. Through thousands of years of weathering these ancient survivors have gently descended from the heights of the Himalayas.

Nature provides a variety of passages in deserts, and forests, mountains, plains, and along rivers and beaches, and they are places of enriching experience. Lives have become entwined around them through ritual, spiritual belief, and the necessity of survival. As shelters and settlements evolved they developed their own passages, reflecting and supporting the patterns of life, allowing us to move safely from place to place.

The Street, like Uluru, makes a passage that joins experiences in a progression. The Promenade, like King’s Canyon, offers a flamboyant passage that surprises and delights. The Cloistered Courtyard, like Kata Juta, provides an enclosed passage offering safety and peace, a place for contemplation. The Look Out, like Palm Valley, is a destination whose passage takes us to a very special place. These are the friends of communal life. Should you be lucky enough to visit Venice, you would enjoy a symphony of passages large and small, magnificent and plain, that unite to tell the story of a City.

These natural and organic passages have enriched our lives; we have been free to use them as some might play a musical instrument. They have invited interpretation and adaptation, and with time, we have learnt how to use the passage to create effect, to delight us while satisfying our needs. This is how cathedrals, hospitals, schools, universities, museums, law courts, and airports can be different buildings with their individual experiences. The art gallery, perhaps the simplest example, is a single passage that invites the enjoyment of art, while the hospital has many passages separating and joining rooms devoted to our care.

Neighbourhoods, towns, cities and nations are known by their famous streets and squares. London, New York and Paris are branded by Trafalgar Square, 5th Avenue, and the Champs Elysees, while Milan is famous for The Galleria. China and Russia are the homes of Tiananmen Square and Red Square. We recognise where we live by the name of a street, we find our way through cities all over the world by navigating passages that are familiar to us all, and the more delightful ones draw us like moths to the light.

For our amusement, the garden maze is an object to enjoy at a distance and a passage of spaces to explore, while the American sculptor Richard Serra arranges great curving steel plates to create powerful sculpted passageways to be experienced within and without. The experience of the passage has become an art form, and the passage itself has become an object of delight.

This is cause for celebration: our reliable old servant, the passage, has risen to lofty heights. There is a deep satisfaction in finding that our everyday behaviour can be a source of pleasure, and expressed as a universal art. Anthropologists tell us our survival depends on being able to pass safely through the stages of life. Little wonder that around the world the passage has become so treasured.

Part 4: Houses

HERE is something we are all expert at: houses. I cannot think of another invention as effective for starting a robust conversation. Like the clothes we choose to wear, the house we live in provides comfort and a chance to show off our individuality. I wonder how many young children draw pictures of where they live?

Part of our expertise in housing comes from visiting and living in a variety of places over a lifetime. Houses are unavoidable. My parents moved house 20 times Since leaving the family home, I have moved 11 times. What a strange thing to remember. Have I really moved 30 times while some people never leave the house they were born in? How much of my life has been spent inside a house of some shape or size?

With three young children, my wife and I lived in a Federation house in a leafy Melbourne street, complete with gardens front and back, a garage, and an upstairs for children’s bedrooms. Except for farm houses, the Federation house of the early 1900s was the first inkling of an Australian rather than an English house. It was love at first sight when we found that house, and we were bemused when the selling agent casually called it a cow. After 10 years of wrestling with our dearly loved house, we came to understand what he had meant. It was built on the wrong part of the block, the sun refused to show itself in the rooms where it was needed most, the bedrooms separated the family badly, there was no welcoming place for the family to gravitate to, and no matter how hard we tried or how much money we spent, that house would not bend to our needs. So much for the promises of Federation!

In those days, we spent summer holidays in a rented house that sat next to a beach and faced north. It was an upside-down house, with bedrooms for children downstairs and family living accommodation upstairs. They were happy days. We were fond of this simple beach house, and were grateful for the ways it made our holidays enjoyable and relaxing, with no wrestling required. After a time, we realised that our Federation house was no match for this, so we sold it and built ourselves an upside down beach house in a street not far away. That was nearly 20 years ago, it was the most rewarding decision we ever made, and a great lesson in appreciating the power of a house.

We might hope for a dream home, a palace, perfection and domestic bliss. Just outside Paris stands such a house called the Villa Savoye, built between 1928 and 1931 and designed by the famous architect LeCorbusier as a retreat for the Savoye family. It was and still is regarded as a pinnacle of modern architecture, an exemplar of a belief in the future way of living. But the Savoye family found the house impossible to live in and fell out with the architect. It is now an empty monument that failed its dream of being a utopian house. When it comes to houses, someone’s dream can be someone else’s nightmare.

Some houses manage to survive for centuries, accommodating family after family after family. The older they get, the more desirable they seem to become. They have a generosity, an adaptability, a flexibility, some timeless way of allowing successive inhabitants to feel at home. A room might have begun its life as a parlour, and found itself being used as a bedroom, a sitting room, a study, a dining room, a morning room, a nursery room, a play room, or even a kitchen. It has been found that the perfect minimum dimension for these accommodating rooms is four metres. Rows of familiar terrace houses have been very successful in this way, their character improving with age, thanks largely to the sensible size of their principal rooms.

Houses have important work to do. They connect us with the surroundings from which they shelter us. They shape our lives, they tell the story of who we are, and they become the touchstones of our memories. They are instruments to be tuned and played to our satisfaction, for our expression and enjoyment. They connect families and guests, and they connect us with the horizon and the sky, the sun and the moon, the wind, the clouds, and the rain. They provide our sense of place, they give us orientation and privacy, and connect us with our neighbourhood. They give us pride, identity and well being.

The man who saw what a telephone could become, Steve Jobs of Apple fame, is known for saying that design is often mistaken for imagining what something looks like rather than what it does. The appearance of things is important when they become an expression of our identity, but if they don’t work they fail. If our housing fails, we are in trouble. Only a few privileged people can afford the luxury of living in a house designed for them; the great majority have no such luck. There is hope that the fortunate people who regulate, design and build most of our houses understand the responsibility they carry. We experts will need to speak up when they let us down.

COMMENTS

October 25, 2015

What a great article by Tim Shannon! It says so much about ourselves and our environment. I thoroughly enjoyed it!

Jellie Wyckelsma

Part of our expertise in housing comes from visiting and living in a variety of places over a lifetime. Houses are unavoidable. My parents moved house 20 times Since leaving the family home, I have moved 11 times. What a strange thing to remember. Have I really moved 30 times while some people never leave the house they were born in? How much of my life has been spent inside a house of some shape or size?

With three young children, my wife and I lived in a Federation house in a leafy Melbourne street, complete with gardens front and back, a garage, and an upstairs for children’s bedrooms. Except for farm houses, the Federation house of the early 1900s was the first inkling of an Australian rather than an English house. It was love at first sight when we found that house, and we were bemused when the selling agent casually called it a cow. After 10 years of wrestling with our dearly loved house, we came to understand what he had meant. It was built on the wrong part of the block, the sun refused to show itself in the rooms where it was needed most, the bedrooms separated the family badly, there was no welcoming place for the family to gravitate to, and no matter how hard we tried or how much money we spent, that house would not bend to our needs. So much for the promises of Federation!

In those days, we spent summer holidays in a rented house that sat next to a beach and faced north. It was an upside-down house, with bedrooms for children downstairs and family living accommodation upstairs. They were happy days. We were fond of this simple beach house, and were grateful for the ways it made our holidays enjoyable and relaxing, with no wrestling required. After a time, we realised that our Federation house was no match for this, so we sold it and built ourselves an upside down beach house in a street not far away. That was nearly 20 years ago, it was the most rewarding decision we ever made, and a great lesson in appreciating the power of a house.

We might hope for a dream home, a palace, perfection and domestic bliss. Just outside Paris stands such a house called the Villa Savoye, built between 1928 and 1931 and designed by the famous architect LeCorbusier as a retreat for the Savoye family. It was and still is regarded as a pinnacle of modern architecture, an exemplar of a belief in the future way of living. But the Savoye family found the house impossible to live in and fell out with the architect. It is now an empty monument that failed its dream of being a utopian house. When it comes to houses, someone’s dream can be someone else’s nightmare.

Some houses manage to survive for centuries, accommodating family after family after family. The older they get, the more desirable they seem to become. They have a generosity, an adaptability, a flexibility, some timeless way of allowing successive inhabitants to feel at home. A room might have begun its life as a parlour, and found itself being used as a bedroom, a sitting room, a study, a dining room, a morning room, a nursery room, a play room, or even a kitchen. It has been found that the perfect minimum dimension for these accommodating rooms is four metres. Rows of familiar terrace houses have been very successful in this way, their character improving with age, thanks largely to the sensible size of their principal rooms.

Houses have important work to do. They connect us with the surroundings from which they shelter us. They shape our lives, they tell the story of who we are, and they become the touchstones of our memories. They are instruments to be tuned and played to our satisfaction, for our expression and enjoyment. They connect families and guests, and they connect us with the horizon and the sky, the sun and the moon, the wind, the clouds, and the rain. They provide our sense of place, they give us orientation and privacy, and connect us with our neighbourhood. They give us pride, identity and well being.

The man who saw what a telephone could become, Steve Jobs of Apple fame, is known for saying that design is often mistaken for imagining what something looks like rather than what it does. The appearance of things is important when they become an expression of our identity, but if they don’t work they fail. If our housing fails, we are in trouble. Only a few privileged people can afford the luxury of living in a house designed for them; the great majority have no such luck. There is hope that the fortunate people who regulate, design and build most of our houses understand the responsibility they carry. We experts will need to speak up when they let us down.

COMMENTS

October 25, 2015

What a great article by Tim Shannon! It says so much about ourselves and our environment. I thoroughly enjoyed it!

Jellie Wyckelsma

Part 5: Gravity

OCCASIONALLY my Mum would warn me to be careful, saying “pride goes before a fall”. Mum was never known to be wrong. I do not recall her being fond of physics or the like, and I am sure that I learnt about Newton and his Universal Law of Gravitation at school, not at home. I am quite certain that she did not explain the Standard Acceleration of Gravity to me. Mum might have encouraged me to learn of Archimedes declaring that he could lift the world, and she definitely had something to do with my appreciation of Shelley, being one of her guiding lights when he wrote of Ozymandias taking a fall that she could have prevented.

A life moving about in this body, balancing on two legs, getting up and down, tiring and resting, getting by with a broken leg, lifting things and moving them about, raising food to the mouth, standing up in a hurry and feeling faint; a life spent in conflict with our constant companion, gravity. At the end of this life, some believe the relief will be so great that they will rise effortlessly to the heavens above, free from gravity’s pull forever. Nothing need be said about the torture of hell.

We should be grateful for this sweet force that stops us from flying into space while keeping us gently grounded. Gravity has a big say in who we are; everything about us and our world evolved in harmony with the universal law Newton discovered for our understanding. We are as tall, heavy and strong as our relationship with gravity has determined, and the satisfaction of our feet being on the ground is thanks to this. Not being content, ever since man could walk about on two legs, he has determined to show how superior to gravity he might be.

Since lifting the first tent pole, totem, obelisk, or beam between two posts; since putting one stone on another, one brick on another, since the first discovery of concrete, iron, and steel, mankind has struggled to conquer gravity. The record shows tall and slender shafts of stone, mystical circular structures, the Tower of Babylon, and magnificent pyramids as examples of successive civilisations displaying their power and might.

The ancients set standards for their successors to exceed in this extraordinary pursuit, so we have seen the likes of the great vaulting dome of the Pantheon and the soaring cathedrals of Gothic times. Since, we have been blessed with the Eiffel Tower and the Empire State Building, the dreams of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Mile High building and Le Corbusiers’s Radiant City, and towering communications structures rising on mountain tops. Now it is fashionable for cities to display Gherkins and Bottle Openers and Shards, and all manner of buildings that twist and demand attention; seeking delight, all claiming to be the world’s grandest and tallest.

It is not long ago that the weight of a stone, a brick, a slate, or timber post or beam was respected before it was lifted into place. There was common understanding of the effort that had gone into the finding and making of those valuable servants of building. However, levers, wheels, ropes, pulleys, cogs and gears, steam, and electricity have been the means by which we have been able to find ever more inventive ways of fighting gravity. It used to be that the height of a building was limited by the number of flights of stairs that was a manageable obstacle to us reaching our destination. Imagine our delight when the very clever Mr Otis thought of a way to use ropes, wheels and a counterbalance to lift us effortlessly upwards like a child on a see saw.

Should you travel through the Australian outback you might wonder about the fate of those deserted farmhouses whose fireplaces and chimneys stand forlornly among their ruins. One of gravity’s tricks is that it works in a straight line, trying its best to reach the earth’s centre as quickly as possible; it has a great aversion to meandering. When our tall endeavours are not truly straight, gravity will grab those unruly parts pulling them back to earth. The wind or occasional earthquake tremor will give a sideways nudge to our towering efforts, and that is a free kick for gravity if you are not ready for it. Those fireplaces and chimneys were built pretty true, and having the luxury of four strong corners to shoulder against any shuddering, they have long outlasted the parts of the house that gravity has consumed. It will be the failing strength of the last brick joints that gravity is waiting for so it can finish its job.

Steel and concrete and more recently the computer have been responsible for discovering all sorts of ways to put gravity to the test. An early victory for steel and concrete saw the demise of the humble pitched roof as the crown of a safe building. It was a place that had provided generations with some delightful accommodation but was no longer needed after flat steel and concrete roofs arrived. So too, columns and slabs of steel and concrete removed the need for supporting walls with their individual window openings; walls can now hang with gravity rather than stand against it!

The dizzy frontiers are now the lofty world of the skyscraper, where anything needs to be embarrassingly huge. The new limit on height is the speed at which the human body can survive vertical travel. But the super tall and big wonders of technology and innovation still need to come to rest and to resist toppling into the clutches of gravity, with its reluctance to meander. The remarkable television centre for the Beijing Olympics, designed by the highly regarded Dutch architects OMA, comprises two very tall parts leaning in balance against each other in defiance of gravity. It was rumoured while the building was going up, the weight required to silence gravity was sufficient to cause a steel shortage in China!

The quest for delight is a part of life; Plato observed this when he roughly said, “He who looks for true beauty will find it”. How wonderful that gravity tempts and rewards us in this search, and that from time to time it brings us back to earth, just like my Mum warned.

A life moving about in this body, balancing on two legs, getting up and down, tiring and resting, getting by with a broken leg, lifting things and moving them about, raising food to the mouth, standing up in a hurry and feeling faint; a life spent in conflict with our constant companion, gravity. At the end of this life, some believe the relief will be so great that they will rise effortlessly to the heavens above, free from gravity’s pull forever. Nothing need be said about the torture of hell.

We should be grateful for this sweet force that stops us from flying into space while keeping us gently grounded. Gravity has a big say in who we are; everything about us and our world evolved in harmony with the universal law Newton discovered for our understanding. We are as tall, heavy and strong as our relationship with gravity has determined, and the satisfaction of our feet being on the ground is thanks to this. Not being content, ever since man could walk about on two legs, he has determined to show how superior to gravity he might be.

Since lifting the first tent pole, totem, obelisk, or beam between two posts; since putting one stone on another, one brick on another, since the first discovery of concrete, iron, and steel, mankind has struggled to conquer gravity. The record shows tall and slender shafts of stone, mystical circular structures, the Tower of Babylon, and magnificent pyramids as examples of successive civilisations displaying their power and might.

The ancients set standards for their successors to exceed in this extraordinary pursuit, so we have seen the likes of the great vaulting dome of the Pantheon and the soaring cathedrals of Gothic times. Since, we have been blessed with the Eiffel Tower and the Empire State Building, the dreams of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Mile High building and Le Corbusiers’s Radiant City, and towering communications structures rising on mountain tops. Now it is fashionable for cities to display Gherkins and Bottle Openers and Shards, and all manner of buildings that twist and demand attention; seeking delight, all claiming to be the world’s grandest and tallest.

It is not long ago that the weight of a stone, a brick, a slate, or timber post or beam was respected before it was lifted into place. There was common understanding of the effort that had gone into the finding and making of those valuable servants of building. However, levers, wheels, ropes, pulleys, cogs and gears, steam, and electricity have been the means by which we have been able to find ever more inventive ways of fighting gravity. It used to be that the height of a building was limited by the number of flights of stairs that was a manageable obstacle to us reaching our destination. Imagine our delight when the very clever Mr Otis thought of a way to use ropes, wheels and a counterbalance to lift us effortlessly upwards like a child on a see saw.

Should you travel through the Australian outback you might wonder about the fate of those deserted farmhouses whose fireplaces and chimneys stand forlornly among their ruins. One of gravity’s tricks is that it works in a straight line, trying its best to reach the earth’s centre as quickly as possible; it has a great aversion to meandering. When our tall endeavours are not truly straight, gravity will grab those unruly parts pulling them back to earth. The wind or occasional earthquake tremor will give a sideways nudge to our towering efforts, and that is a free kick for gravity if you are not ready for it. Those fireplaces and chimneys were built pretty true, and having the luxury of four strong corners to shoulder against any shuddering, they have long outlasted the parts of the house that gravity has consumed. It will be the failing strength of the last brick joints that gravity is waiting for so it can finish its job.

Steel and concrete and more recently the computer have been responsible for discovering all sorts of ways to put gravity to the test. An early victory for steel and concrete saw the demise of the humble pitched roof as the crown of a safe building. It was a place that had provided generations with some delightful accommodation but was no longer needed after flat steel and concrete roofs arrived. So too, columns and slabs of steel and concrete removed the need for supporting walls with their individual window openings; walls can now hang with gravity rather than stand against it!

The dizzy frontiers are now the lofty world of the skyscraper, where anything needs to be embarrassingly huge. The new limit on height is the speed at which the human body can survive vertical travel. But the super tall and big wonders of technology and innovation still need to come to rest and to resist toppling into the clutches of gravity, with its reluctance to meander. The remarkable television centre for the Beijing Olympics, designed by the highly regarded Dutch architects OMA, comprises two very tall parts leaning in balance against each other in defiance of gravity. It was rumoured while the building was going up, the weight required to silence gravity was sufficient to cause a steel shortage in China!

The quest for delight is a part of life; Plato observed this when he roughly said, “He who looks for true beauty will find it”. How wonderful that gravity tempts and rewards us in this search, and that from time to time it brings us back to earth, just like my Mum warned.

Part 6: Rooms

GOOD rooms and good friends have much in common. With them, or enjoying memories of them, they give support, comfort and delight, helping life along. There are a few favourites, some close, and several distant. They require a spark of attraction, time and care. They are touch points and shining lights in life’s meanderings. From birth we need protection, comfort and nurturing, and rooms and friends provide us with these essentials.

Who can recollect their first room, the place where consciousness began, where our senses started work on building our personal rooms of awareness? With time this room grows richer as we judge new things against those we have learnt from in the past. So it might not be surprising that along the way we have created a collection of real rooms to serve and delight us.

Bed room, dining room, living room, reading room, ball room, billiard room, bathroom, spare room, back room, front room, corner room, top room, class room, court room, mess room, green room ... plus foyer, lobby, hall, auditorium, nave, chamber, office, laboratory, bar, scullery, kitchen, laundry, larder ... just to name a few. Then add cars, trains, ships and planes! Our time spent outside rooms is surely limited.

What if there were no rooms? The Market is a grand room to visit, a pleasure anywhere you find one. But the supermarket or department store are more of a tiresome obligation. They rob us of our bearings and bamboozle us to exhaustion. No sense of location, no choice of direction, no way out, no sense of time, no sense of outside, no individuality; just being herded with strangers through a morass of confusion. These are worlds without rooms.

The first job of a room is to make sense, to let you know who it is. A room should be direct in describing its intended purpose as well as giving some clues about how it might be adapted to suit different circumstances. A room should indicate the character of who built it and how they cared about their work, and demonstrate an understanding of those who enter. For instance, the courtroom is a pinnacle of sophistication for rooms, it states its unbending purpose most clearly; and while the barn or such like may be humble, it is a pinnacle of generosity and adaptability.

Another job for rooms is to accommodate our desire to decorate and collect. The floor, walls, and ceiling of a room may be centuries old, and will have hosted a multitude of carpets, rugs, skins, drapes, shutters, blinds, coats of plaster and paint, panelling, mirrors, paintings, trophies, sculptures, tables, chairs, cupboards, shelves, lights, heaters, coolers, appliances, and so on. When the room is emptied of our clutter, it politely resumes its immutable self. A good room humours our territorial need for possessions. This is how Mr Ikea has been able to put his clutter into more rooms around the world than any other human, so far at least.

Should you be wanting authentic comfort, hotel rooms are strange places. Mr Hilton, for example, has colonised the world by building identical rooms everywhere, ensuring that each of his guests will enjoy the same Hilton hospitality and experience. I have been his occasional guest in Adelaide for thirty years or so, and with familiarity comes a mirage of comfort. Mr Hilton ruined this illusion when he put me into a room which was unkempt and being slept in by another, and then moved me to the well prepared room directly below. I was reminded that I was just another body in another room used by other bodies, and somebody was in “my” room immediately above. Small hotels are more honest.

We demand a lot of our rooms, with our different expectations of the same space. Within their walls and corners we find our place, through their windows we connect with outside, their orientation fixes our compass, and their aspect tells of the passing of the day. They provide the places where life’s story is written. They adapt to our changing needs, and they safeguard our memories. Life’s rituals are entwined with the rooms that play host to our feelings of happiness and sadness, hope and despair. A first day at school, a birthday or wedding, a holiday, or a new job, each remembered along with the room we were in.

Mornings at home I enjoy breakfast in our living room, which is where we cook, eat, relax and occasionally entertain friends. The room has most of our personal possessions visible on walls, benches, shelves and tables, or in cupboards; things that have taken forty years to make or collect, each one a reminder of some place, some time, some body, or a favourite book. I sit in the same chair at the dining table facing north to the distant view, the morning light to my right, and the sky suggesting what weather the day will bring. Tea time arrives when the sun has traversed the sky and the evening light is to my left, and I sit again in the same chair among family and familiar surroundings. Pure, simple delight.

COMMENTS

February 13, 2016

Thank you for taking me back to my first memory of a room. It made me very happy to remember the little room which was bed, dining, lounge room for our family of four. It was heated by a huge clay tiled coal oven and was the only heated room in our two room flat, during freezing Polish winters.

Felicia Di Stefano, Glen Forbes

Who can recollect their first room, the place where consciousness began, where our senses started work on building our personal rooms of awareness? With time this room grows richer as we judge new things against those we have learnt from in the past. So it might not be surprising that along the way we have created a collection of real rooms to serve and delight us.

Bed room, dining room, living room, reading room, ball room, billiard room, bathroom, spare room, back room, front room, corner room, top room, class room, court room, mess room, green room ... plus foyer, lobby, hall, auditorium, nave, chamber, office, laboratory, bar, scullery, kitchen, laundry, larder ... just to name a few. Then add cars, trains, ships and planes! Our time spent outside rooms is surely limited.

What if there were no rooms? The Market is a grand room to visit, a pleasure anywhere you find one. But the supermarket or department store are more of a tiresome obligation. They rob us of our bearings and bamboozle us to exhaustion. No sense of location, no choice of direction, no way out, no sense of time, no sense of outside, no individuality; just being herded with strangers through a morass of confusion. These are worlds without rooms.

The first job of a room is to make sense, to let you know who it is. A room should be direct in describing its intended purpose as well as giving some clues about how it might be adapted to suit different circumstances. A room should indicate the character of who built it and how they cared about their work, and demonstrate an understanding of those who enter. For instance, the courtroom is a pinnacle of sophistication for rooms, it states its unbending purpose most clearly; and while the barn or such like may be humble, it is a pinnacle of generosity and adaptability.

Another job for rooms is to accommodate our desire to decorate and collect. The floor, walls, and ceiling of a room may be centuries old, and will have hosted a multitude of carpets, rugs, skins, drapes, shutters, blinds, coats of plaster and paint, panelling, mirrors, paintings, trophies, sculptures, tables, chairs, cupboards, shelves, lights, heaters, coolers, appliances, and so on. When the room is emptied of our clutter, it politely resumes its immutable self. A good room humours our territorial need for possessions. This is how Mr Ikea has been able to put his clutter into more rooms around the world than any other human, so far at least.

Should you be wanting authentic comfort, hotel rooms are strange places. Mr Hilton, for example, has colonised the world by building identical rooms everywhere, ensuring that each of his guests will enjoy the same Hilton hospitality and experience. I have been his occasional guest in Adelaide for thirty years or so, and with familiarity comes a mirage of comfort. Mr Hilton ruined this illusion when he put me into a room which was unkempt and being slept in by another, and then moved me to the well prepared room directly below. I was reminded that I was just another body in another room used by other bodies, and somebody was in “my” room immediately above. Small hotels are more honest.

We demand a lot of our rooms, with our different expectations of the same space. Within their walls and corners we find our place, through their windows we connect with outside, their orientation fixes our compass, and their aspect tells of the passing of the day. They provide the places where life’s story is written. They adapt to our changing needs, and they safeguard our memories. Life’s rituals are entwined with the rooms that play host to our feelings of happiness and sadness, hope and despair. A first day at school, a birthday or wedding, a holiday, or a new job, each remembered along with the room we were in.

Mornings at home I enjoy breakfast in our living room, which is where we cook, eat, relax and occasionally entertain friends. The room has most of our personal possessions visible on walls, benches, shelves and tables, or in cupboards; things that have taken forty years to make or collect, each one a reminder of some place, some time, some body, or a favourite book. I sit in the same chair at the dining table facing north to the distant view, the morning light to my right, and the sky suggesting what weather the day will bring. Tea time arrives when the sun has traversed the sky and the evening light is to my left, and I sit again in the same chair among family and familiar surroundings. Pure, simple delight.

COMMENTS

February 13, 2016

Thank you for taking me back to my first memory of a room. It made me very happy to remember the little room which was bed, dining, lounge room for our family of four. It was heated by a huge clay tiled coal oven and was the only heated room in our two room flat, during freezing Polish winters.

Felicia Di Stefano, Glen Forbes

Part 7: Plans

MANY stories are passed on through buildings, music, and literature. A set of plans, a musical score, a poem, or a novel, each is a product of the imagination and our instinct for beauty, our need to find order amongst chaos. Some have claimed that architecture is the most important of the arts, and it might be true that we cannot escape our buildings’ touch.

While a map records what exists, a plan can be an idea for the future. A plan asserts ownership, control, and determination. A plan that is adaptable, open to suggestion and interpretation will endure, while a rigid and unrelenting plan will become useless. A plan requires good mapping as its foundation, and visionary minds for its creation.

Preparing a plan is a meditation. Beginning with ideas and a blank page, every mark that is made has a meaning. The first dot, the first line, the first shape; each signifies objects and experiences thoughtfully located in space. Organising, arranging, responding, revising, comparing, measuring, keeping, rejecting, refining; desire and imagination, the eye and the hand, working together under the influence of those original ideas.

Plans are stories to read. Australian Aboriginal people make sand painting illustrations of some of their stories, wiping the sand away when the story ends, leaving memory and language to protect the tales.

Helping his daughters remember the order of English kings and queens, Mark Twain had them select clues along their winding driveway to signify each monarch in the order of their reign. The driveway told the tale with every passing. A family’s story is told by the plan of their house. The stories of civilisation are told by the plans of cities.

Works of music and literature have beginnings and endings, as do rituals and events. Plans have more in common with painting and sculpture; they are thoughtful compositions explored in many ways. They are spatial and experiential, open to interpretation, mirroring our behaviour and our lifetime of learning. They fuel our imagination and become part of our memories, each encounter being unique.

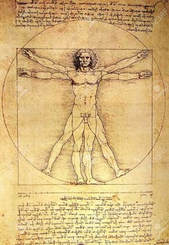

Plans are minute representations of the infinite, helping the complex to appear simple. They are composed by us and of us. The human figure has been used in plans for thousands of years. Ancient Egyptians used their feet, forearms and so on for measuring length. The spread of our hands, the width of our fingers, and the length of our stride are comfortable aids to estimating the size of things. Leonardo Da Vinci’s drawing of the Vitruvian Man beautifully summarises our fascination with the mystics of geometry, proportion, symmetry, and natural harmony. The quest for order has long been of cosmological interest, and today distance is a measure of the speed of light calculated in atomic increments, while time is calibrated by the pulse of atom. Some believe we have finally discovered the secrets of universal harmony.

The authors of our plans carry a great responsibility. They have held important positions in past civilisations, the keepers of mystical secrets, the members of guilds and societies, the confidants of the rich and the powerful. It is thought that the authors of Egyptian temples and pyramids were executed if they made mistakes, and there is a myth that the authors of the Taj Mahal were blinded to prevent them from duplicating their work. We expect the creators of plans of buildings to provide us with “firmness, commodity, and delight”.

The beauty of plans rests in how they take intangible hopes and ideas, and use them to create a vision that can be shared and realised. They provide hope. To re-arrange the furniture in a room, change a shed into a house, build a new parliament house, or build a new city, we need an author to create a plan.

In the early 1830s a group of Englishmen needed an author to help them with their vision. Inspired by the reformer Edward Gibbon Wakefield, they came together to build a colonial utopian city. Here the citizens would own their home and an acre of land, lead self-sufficient lives, and be free to choose their own faith; and so, the South Australia Company commissioned Colonel William Light to select a site, and to prepare a plan for the garden city of Adelaide.

Light was a surveyor, skilled at preparing maps. He surveyed the plain between St Vincent’s Gulf and the Mount Lofty Ranges which was crossed by the River Torrens, so learning the intimate details of his chosen site. What he did next was poetic. In the summer, he created a plan which responded to the rise and fall of the land, the winding of the river, the presence of the ranges, the proximity of the coast, the passage of the sun, the needs of the settlers, the financial demands of the founders and, most importantly, to the vision that was the catalyst for this bold undertaking. His achievement is beautifully illustrated by just two plans: one explains the siting and the other explains a new way of life.

Visiting Adelaide some 180 years later we can see how Colonel Light’s plan has coped with the changing demands put upon it, many people being unaware of the aspirations that were its foundation, but each making judgements about what they find.

The ultimate measure of success for our plans is their ability to continue to delight and serve us well. Shooting stars are not the substance of enduring plans, but lofty ideals are handy.

COMMENTS

March 22, 2016

Thanks Tim for another beautifully written piece. I love the way you mesh the past and the present, compare and contrast the role of the various arts in architecture and shine a light on the place of imagination as well as technique and skill in creating the buildings, towns and cities in which we live.

Linda Cuttriss, Phillip Island

While a map records what exists, a plan can be an idea for the future. A plan asserts ownership, control, and determination. A plan that is adaptable, open to suggestion and interpretation will endure, while a rigid and unrelenting plan will become useless. A plan requires good mapping as its foundation, and visionary minds for its creation.

Preparing a plan is a meditation. Beginning with ideas and a blank page, every mark that is made has a meaning. The first dot, the first line, the first shape; each signifies objects and experiences thoughtfully located in space. Organising, arranging, responding, revising, comparing, measuring, keeping, rejecting, refining; desire and imagination, the eye and the hand, working together under the influence of those original ideas.

Plans are stories to read. Australian Aboriginal people make sand painting illustrations of some of their stories, wiping the sand away when the story ends, leaving memory and language to protect the tales.

Helping his daughters remember the order of English kings and queens, Mark Twain had them select clues along their winding driveway to signify each monarch in the order of their reign. The driveway told the tale with every passing. A family’s story is told by the plan of their house. The stories of civilisation are told by the plans of cities.

Works of music and literature have beginnings and endings, as do rituals and events. Plans have more in common with painting and sculpture; they are thoughtful compositions explored in many ways. They are spatial and experiential, open to interpretation, mirroring our behaviour and our lifetime of learning. They fuel our imagination and become part of our memories, each encounter being unique.

Plans are minute representations of the infinite, helping the complex to appear simple. They are composed by us and of us. The human figure has been used in plans for thousands of years. Ancient Egyptians used their feet, forearms and so on for measuring length. The spread of our hands, the width of our fingers, and the length of our stride are comfortable aids to estimating the size of things. Leonardo Da Vinci’s drawing of the Vitruvian Man beautifully summarises our fascination with the mystics of geometry, proportion, symmetry, and natural harmony. The quest for order has long been of cosmological interest, and today distance is a measure of the speed of light calculated in atomic increments, while time is calibrated by the pulse of atom. Some believe we have finally discovered the secrets of universal harmony.

The authors of our plans carry a great responsibility. They have held important positions in past civilisations, the keepers of mystical secrets, the members of guilds and societies, the confidants of the rich and the powerful. It is thought that the authors of Egyptian temples and pyramids were executed if they made mistakes, and there is a myth that the authors of the Taj Mahal were blinded to prevent them from duplicating their work. We expect the creators of plans of buildings to provide us with “firmness, commodity, and delight”.

The beauty of plans rests in how they take intangible hopes and ideas, and use them to create a vision that can be shared and realised. They provide hope. To re-arrange the furniture in a room, change a shed into a house, build a new parliament house, or build a new city, we need an author to create a plan.

In the early 1830s a group of Englishmen needed an author to help them with their vision. Inspired by the reformer Edward Gibbon Wakefield, they came together to build a colonial utopian city. Here the citizens would own their home and an acre of land, lead self-sufficient lives, and be free to choose their own faith; and so, the South Australia Company commissioned Colonel William Light to select a site, and to prepare a plan for the garden city of Adelaide.

Light was a surveyor, skilled at preparing maps. He surveyed the plain between St Vincent’s Gulf and the Mount Lofty Ranges which was crossed by the River Torrens, so learning the intimate details of his chosen site. What he did next was poetic. In the summer, he created a plan which responded to the rise and fall of the land, the winding of the river, the presence of the ranges, the proximity of the coast, the passage of the sun, the needs of the settlers, the financial demands of the founders and, most importantly, to the vision that was the catalyst for this bold undertaking. His achievement is beautifully illustrated by just two plans: one explains the siting and the other explains a new way of life.

Visiting Adelaide some 180 years later we can see how Colonel Light’s plan has coped with the changing demands put upon it, many people being unaware of the aspirations that were its foundation, but each making judgements about what they find.

The ultimate measure of success for our plans is their ability to continue to delight and serve us well. Shooting stars are not the substance of enduring plans, but lofty ideals are handy.

COMMENTS

March 22, 2016

Thanks Tim for another beautifully written piece. I love the way you mesh the past and the present, compare and contrast the role of the various arts in architecture and shine a light on the place of imagination as well as technique and skill in creating the buildings, towns and cities in which we live.

Linda Cuttriss, Phillip Island

Part 8: Familiarity

WE CANNOT resist the temptation to make the unfamiliar familiar. The iPhone was a strange thing at first sight; was it a phone, a camera, a diary, a radio, a calculator? It turns out that its appearance had little to do with its transition from unfamiliar to familiar. It made sense to us by responding to our need to communicate, provided delight, and now has become an inseparable companion. The telephone has changed from being a luxury to a necessity; using one has changed from being a chore to being entertaining; and information control has become information sharing.

The unfamiliar can be threatening. “It is in Italy that we issue this manifesto of ruinous and incendiary violence, by which we today are founding Futurism, because we want to deliver Italy from its gangrene of professors, archaeologists, tourist guides and antiquaries,” wrote a young Marinetti in his manifesto of 1909.

The familiar can stifle change and entrench the past. For thousands of years the Parthenon has remained a symbol of authority, prestige, and ageless beauty; while it was in the homeland of the Eternal City that Marinetti, the revolutionary, shouted about the hope that comes with liberation from the past and the excitement of an unfamiliar future.

Our built world is a library of the familiar, where countless experiences are remembered, learned, referred, stored, evaluated, improved, and possibly rejected. It is a laboratory where admiration and contempt are the poles of opinion. It nurtures our interest in the unfamiliar, and saves us from being prisoners of the familiar as we come to terms with the changes thrust upon us. We see there was a time when there were no palaces, temples, theatres, galleries, arenas, hospitals, universities, airports, skyscrapers. When a church looked like a church and a house looked like a house. When there was no steel, glass, concrete, or bricks. Looking into the past we learn that, just like the telephone, the appearance of things will change, confronting, disappointing and delighting us ; but what matters most is how we live with our built world, and that it makes sense.

Style might be said to be the friend of familiarity, while innovation might claim to be the friend of unfamiliarity. Throughout architectural history there has been a practice of identifying, cataloguing, recording, and promulgating styles. This has illuminated the past and the familiar. It has formed the basis of architectural education, and has separated teaching from practising. The great revolutions of unfamiliarity recorded in our library of past experiences are the products of technological innovation and major social change, not changes of style.

In the western world, it might be said that our sophisticated library begins with the Ancient Greeks; their temple being the equivalent of Alexander Bell’s first telephone. The iPhone equivalent of today’s built world results from innovations in building and designing technology, and is fuelled by social change. When Jørn Utzon’s Sydney Opera House was opened in 1973, it was perhaps the first glimpse of an unbridled future for our built world. Precast concrete, high tensile steel, glass, computer technology, and national pride made this possible. Frank Ghery’s gallery in Bilbao some 20 years later displayed the ability of computer-aided design to copy any imaginable object. Zaha Hadid’s recent gallery in Rome hints at the potential of designing by computer and how once familiar spaces can become delightful unfamiliar inventions.

Don’t be tricked into believing that rarity always wins admiration. We are mighty tough critics of most things, but especially anything new. We can see through pretence and flimflam, we have a healthy disregard for tall poppies. For the unfamiliar to be adopted by the ranks of the familiar, it must make sense and have an authentic connection to daily life.

Don’t be afraid either. When you look through the great library of our familiar world you can be reassured by the wisdom of human communities to be good critics; you can see the results of a rich diversity of inquiry, the successes and the failures; and you might wonder what you would see if the world remained forever familiar.

COMMENTS

May 7, 2016

Professor Shannon’s thought-provoking articles continue to challenge our understanding of evolutionary architecture. Are we blessed, threatened or challenged by technology. The unlimited expansion of ideas driven by technological change allows us to escape familiarity and apply our creative vision to embrace the unfamiliar.

Ian Samuel

The unfamiliar can be threatening. “It is in Italy that we issue this manifesto of ruinous and incendiary violence, by which we today are founding Futurism, because we want to deliver Italy from its gangrene of professors, archaeologists, tourist guides and antiquaries,” wrote a young Marinetti in his manifesto of 1909.

The familiar can stifle change and entrench the past. For thousands of years the Parthenon has remained a symbol of authority, prestige, and ageless beauty; while it was in the homeland of the Eternal City that Marinetti, the revolutionary, shouted about the hope that comes with liberation from the past and the excitement of an unfamiliar future.