Somewhere between necessity and beauty,

Somewhere between necessity and beauty, the making of things is a gift in itself

By Tim Shannon

IN MY bedroom above a chest of drawers hangs a small black and white photograph that was taken by my father. It shows my mother holding my four year old hand on a wintery day outside a gate of Windsor Castle. She is wearing a long woollen coat that I can recall nestling into, and her face is happy. Occasionally I pause to look at it, usually in the quiet of early morning, and my thoughts turn to childhood memories.

Like all houses, ours has an eclectic variety of objects that we keep. Some are made by strangers, some are rocks, bones, and shells found while walking, some are made by the family, some are gifts from friends, some are paintings, some are photographs, some are pieces of furniture, some are clothes, some are children’s toys, some we can’t find but we are sure they are there somewhere. Given enough quiet time, each of them has a story to tell.

IN MY bedroom above a chest of drawers hangs a small black and white photograph that was taken by my father. It shows my mother holding my four year old hand on a wintery day outside a gate of Windsor Castle. She is wearing a long woollen coat that I can recall nestling into, and her face is happy. Occasionally I pause to look at it, usually in the quiet of early morning, and my thoughts turn to childhood memories.

Like all houses, ours has an eclectic variety of objects that we keep. Some are made by strangers, some are rocks, bones, and shells found while walking, some are made by the family, some are gifts from friends, some are paintings, some are photographs, some are pieces of furniture, some are clothes, some are children’s toys, some we can’t find but we are sure they are there somewhere. Given enough quiet time, each of them has a story to tell.

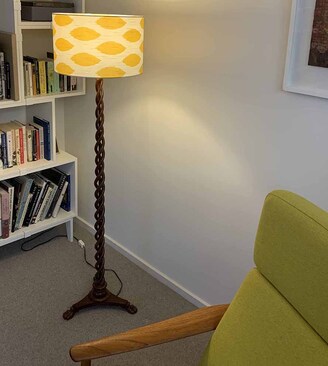

We have a room in our house which looks north into a small court of Japanese maples that keep time with the changing seasons of the year. The room started its life as a lounge for our teenage children, and somewhere to do the ironing. The children left several years ago, and in place of their television is a wall of books and two comfortable chairs. It is still where the ironing gets done, but the room also hosts the standard lamp that my father made in his teenage years.

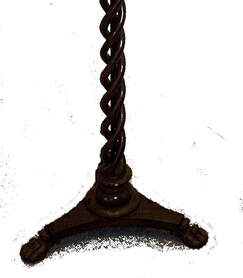

In Canberra, in a room where my sister lives, is a desk lamp that my father made as a companion to the standard lamp. These lamps were carved from mahogany, they have elegant triangular bases with lions feet at each corner, an ornate crown to hold the lamp, and a beautiful column which joins the base to the crown which is carved from a single length in the form of three tapering, entwined and separate spirals which glisten gently in the light.

Somewhere unknown in another room my sister and I hope there rests an exquisite bust of Shakespeare also carved from mahogany by our teenage father. It was stolen many years ago, but is still a source of memories of quiet contemplation and admiration. Dad spent many hours in the company of an Italian cabinet maker called Santi who lived with my grandparents, and who shared his knowledge and love of wood carving with their youngest son. When I sit in our sunny room on an autumn afternoon, the standard lamp continues to be the source of comfort that it was for him.

Recently I made a few drawings to help build a roof garden for our home. I used my “tools of the trade”, a small drawing board, tee square and set square, a scale, propelling pencil and a pen, and some sheets of tracing film. After a time, I found myself drawing very small closely spaced lines, and fell under the spell of each new line flowing from the tip of the pen, and I was reminded of the reverie of drawing patiently in solitude, most often in the quiet of night, the dignified ritual of making drawings.

Then I am reminded of learning to write, starting with the letters of the alphabet, hearing the sound of each one while my fingers guided a pencil to repeat their shapes time after time in row after row. The same might be said for learning music, dancing, drawing, weaving, farming, and all the other ways in which we come to enjoy making things, where simply digging a hole in the ground can be satisfying. Things made can be valued for their usefulness, and treasured for their beauty. They can bring contentment to their maker, as well as the reassurance of praise. In their making lies pleasure and pain, in the beauty of the finished work lies satisfaction, but be wary of the fate of Ozymandias:

“And on the pedestal these words appear:

‘My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings:

Look upon my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far way.”

(These are the closing lines of the poem Ozymandias by Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1818; my Mum just said, “Look out, pride comes before a fall!”)

Between pleasure and pain, and necessity and beauty, the making of things is a continuous occupation for mankind. Incredible stories of creation come from our longing to understand how we and our world and its universe were made and by whom. The museums of nations are full of objects we have made, ranging from brilliant inventions of necessity to exquisite creations whose sole purpose is to be admired. Each of these carries the story of their maker, their making, their past; and the quiet reverie of all makers becomes an intrigue for audiences that were never expected.

Sometimes we just make things for our own fulfillment. We find comfort in the solitude which allows us to explore our private thoughts and aspects of ourselves that daily life often won’t. We enjoy the struggle while we attempt to forge things that are expressions and glimpses of who we are. With this story I have been following my thoughts like a sailor who keeps an eye out for the wind.

Somewhere unknown in another room my sister and I hope there rests an exquisite bust of Shakespeare also carved from mahogany by our teenage father. It was stolen many years ago, but is still a source of memories of quiet contemplation and admiration. Dad spent many hours in the company of an Italian cabinet maker called Santi who lived with my grandparents, and who shared his knowledge and love of wood carving with their youngest son. When I sit in our sunny room on an autumn afternoon, the standard lamp continues to be the source of comfort that it was for him.

Recently I made a few drawings to help build a roof garden for our home. I used my “tools of the trade”, a small drawing board, tee square and set square, a scale, propelling pencil and a pen, and some sheets of tracing film. After a time, I found myself drawing very small closely spaced lines, and fell under the spell of each new line flowing from the tip of the pen, and I was reminded of the reverie of drawing patiently in solitude, most often in the quiet of night, the dignified ritual of making drawings.

Then I am reminded of learning to write, starting with the letters of the alphabet, hearing the sound of each one while my fingers guided a pencil to repeat their shapes time after time in row after row. The same might be said for learning music, dancing, drawing, weaving, farming, and all the other ways in which we come to enjoy making things, where simply digging a hole in the ground can be satisfying. Things made can be valued for their usefulness, and treasured for their beauty. They can bring contentment to their maker, as well as the reassurance of praise. In their making lies pleasure and pain, in the beauty of the finished work lies satisfaction, but be wary of the fate of Ozymandias:

“And on the pedestal these words appear:

‘My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings:

Look upon my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far way.”

(These are the closing lines of the poem Ozymandias by Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1818; my Mum just said, “Look out, pride comes before a fall!”)

Between pleasure and pain, and necessity and beauty, the making of things is a continuous occupation for mankind. Incredible stories of creation come from our longing to understand how we and our world and its universe were made and by whom. The museums of nations are full of objects we have made, ranging from brilliant inventions of necessity to exquisite creations whose sole purpose is to be admired. Each of these carries the story of their maker, their making, their past; and the quiet reverie of all makers becomes an intrigue for audiences that were never expected.

Sometimes we just make things for our own fulfillment. We find comfort in the solitude which allows us to explore our private thoughts and aspects of ourselves that daily life often won’t. We enjoy the struggle while we attempt to forge things that are expressions and glimpses of who we are. With this story I have been following my thoughts like a sailor who keeps an eye out for the wind.