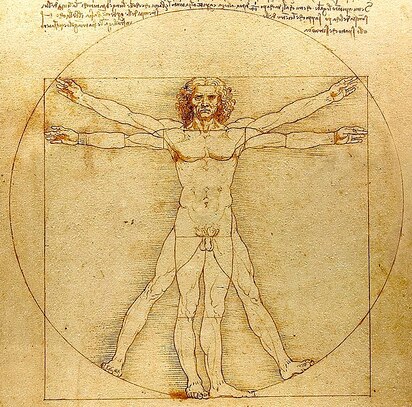

Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, drawn in about 1490, is believed to be

Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, drawn in about 1490, is believed to be a self-portrait. In an accompanying note da Vinci wrote: “The proportions

of the human body according to [Roman architect] Vitruvius”.

By Tim Shannon

I AM host to the mind of an architect. For nearly seventy years I have listened to its voice and experienced its thoughts and emotions; together we have accumulated a vast library of images and explored a myriad of places in our dreams. Despite my trying, I cannot be anyone other than me, and I cannot be any other architect than the one I am. All the while my path has been the servant of chance and hope, being occasionally guided by a kindly soul.

At first I did not know what it was to be an architect, or what architecture might be. My mind was a pure blank page, unspoiled, anticipating. The first wisps to enter this void were revered but vague opinions claiming that architecture was “firmness, commodity and delight”, “frozen music”, “the magnificent play of light on volumes in space”, or “the greatest of the arts”. Like the ancient guilds, architecture for the uninitiated was discussed in codes, admission was guarded, and its prestige lay in its mystique.

As a student I came to believe that the architect had a gift, a creative mind capable of inspired ideas that could be built, and that these built things would mysteriously “make the world a better place.” This was the time of modernism when architects were masters, whose opinions and ideas were trusted, and whose success was measured by their fame.

In 1972 a public housing project called Pruitt-Igoe was demolished in St. Louis, America. It was designed in the 1950s by a modernist architect and it was razed to the ground because its architecture made it unsuitable to live in. The detonation of its buildings signified an end to modernism.

Some time before this, in my first year as an architecture student in Adelaide, I remember orientation week, when a Canadian-American called Jane Jacobs was a guest. We students were herded on a hill side to form the letters J A N E. I had no idea that she was an activist protesting the wrongs of modernism or that she would be remembered as the founder of modern urban design. I would not read her book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, until some thirty years later.

So I entered the world of employment, well qualified but not well educated. There were happy newly married days in Sydney, a job, new friends, a random parade of people and conversations, all of which somehow resulted in my leaving for Toronto. It was all chance and hope, and I had no answer to my conundrum.

In the afternoon of a winter’s Sunday in 1975, I was making my way to John Andrews’ Pink House in Palm Beach, Sydney. I found him sitting quietly in his bedroom where we talked for a while. I was leaving for Toronto in the next few days. A friend had persuaded me that I needed to study in North America, so I found a job with John because he had studied at Harvard. I made a handful of applications to American universities which failed. John stepped in to help, he had been Chairman of the Architecture School at Toronto University, he secured me a place in the masters program, and he changed my life.

Peter Prangnell was chosen by John to run the Architecture School at Toronto, and Peter provided me with direction and hope. He introduced me to the idea that architecture was like literature. He celebrated the unexpected. He introduced me to Aldo Van Eycks’s humanistic view of architecture, and he shared his insights into the work of Le Corbusier. Most helpful of all is the memory of him telling me how he began to understand architecture while photographing the parts of buildings rather than their whole.

Now I can realise that, like Jane Jacobs, Peter shone a light on how important it is to look and learn about the relationship between behaviour and its setting. They turned “form follows function” on its head to become “function follows form”. Then, it was very satisfying to be able to write, “Architecture is the poetic arrangement of places “, and to think about how I might practise.

There is an old joke which goes, “How do you make a small fortune ? By giving a large one to an architect.” If the hardships of practice were explained before signing up, membership would take a sharp decline. Faithful to the secret traditions of the guilds, these things cannot be taught, they are learned by doing. Practice is full of heartbreak and anguish, but is punctuated from time to time by moments of soaring satisfaction.

Guided by hope, it seemed I needed my own practice, which meant returning to Adelaide. The decision to leave John Andrews was fraught. My wife and I had returned from Toronto broke, we were expecting our first child, we were giving up Palm Beach for Adelaide. I needed a job. I tried three practices, and only Hassell and Partners could offer me a place.

The first days were a bit of a shock, having been accustomed to working in board shorts and taking midday surfs back in Palm Beach. There had been no more than ten in the office, and the projects were few but prestigious. Now I was sitting in a row, along with twenty new colleagues. Surfing was replaced by morning and afternoon tea breaks, and the projects were numerous and varied. The partner I spent most time working with was a likeable, talented, and astute man called John Morphett.

John had studied and worked under Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus, so he was a disciple of design by collaboration, and had been instrumental in changing the way Hassell and Partners worked. In John I chanced to find someone whose idea of practice was a comfort to me. I worked closely with him for over twenty years, and I shed tears when he retired from the practice.

Collaboration is a difficult way to design. It rejects the idea of a single expert, and thrives on disagreement. It rejects style believing that each project deserves its own solution. At the Bauhaus, technology collaborated with art to efficiently improve the lives of all. At Hassell and Partners, architects collaborated with landscape architects, planners, and interior designers, to do the same.

I worked long and hard at building the reputation and collaborative culture of the practice, all the while experiencing the tension between influencing and doing. This Adelaide collaborative became one of Australia’s most successful architectural design firms, and I became the captive of a thousand people, three dozen partners, and endless travel.

Graeme Gunn, an architect friend, had been kindly encouraging me to reflect on my circumstance. My wife was sure I was crazy. Now I recall clearly the bus ride from Perth to Bunker Bay, travelling to another conference. Sitting alone near the back by a window and pondering my malaise, I realised that I could choose to leave this tiring path.

And so I did, with no plan other than wanting to find the self I had lost. With time and luck I became an outsider looking at architecture through the eyes of others. I served on company boards including an urban redevelopment authority, and a privately owned building company, and I spent time on a regional community committee. Most fortunate of all, I met a journalist called Catherine Watson who encouraged me to write, and was willing to publish my efforts.

During these days, around the table of a “Dean’s Lunch” someone asked “What is the point of architecture?” Within their guild architects can fall victim to narcissism and lose sight of “the point”. Back then my creed reassured me that without architecture, buildings would lack poetry, this was the point.

But my time in the laity was creating doubts. What is this “poetry in architecture” and is anyone really interested in it? Quite so, what is the point? The Roman architect Vitruvius wrote in the first century BC that architecture was the product of “firmness, commodity, and delight”, something I was taught a long time ago. Now it returned to taunt me. I may have learnt the ways of firmness and commodity, but I never managed to master the problem of delight.

Looking from the outside, I came to write, “The responsibility of the architect is to create delight”.

I found myself questioned the nature of delight, contemplating and writing, following my roaming mind, capturing thoughts here are there in the clouds before they vanished. I wondered how delight might be experienced in such things as doors, windows, passages, rooms, and houses, and in the awareness of the familiar and the unfamiliar. I pondered the nature of bliss. With the encouragement of Catherine, this resulted in a series of essays.

By chance, Graeme suggested that I should use my essays as the basis of a design studio for students. And so it was, over two years I led a studio founded on the manifesto, “It is the responsibility of architects to create delight in their work”.

The students of “Studio Delight”, like prospectors panning for gold, hunted for delights in our homes. Among the nuggets they found were scale, texture, materials, colours, patterns, light, shade, smell, sound, silence, view, height, surprise, comfort, contrast, flexibility, privacy, community, children, gardens, trees, water, dawn, dusk, wind, rain, clouds, stars, dining, music, art, fire, touch, craftsmanship, culture, rituals, movement, play, and familiarity. Vitruvius had the beauty of the Goddess Venus in mind when he was writing about delight, so this this list might surprise him, maybe even delight him!

Recently I chanced to see a beautiful French film called Portrait of a Lady on Fire which explores the relationship between the portrait artist Marianne and her subject Heloise. There is a scene when Heloise sees her portrait for the first time. She reacts, “But, that is not me,” and Marianne replies “But it is you, I painted your portrait according to the accepted principles, perfectly.” “Yes, but that is not who I am,” says Heloise.

This reminded me of the architects’ dilemma at the first presentation of a design to an expectant client. The fear of failure, and the relief of success. Just now my mind returns to Peter Prangnell likening architecture to the grit in an oyster that results in the creation of a pearl, the delight of an unexpected yet enriching disturbance. Such is the fine balance between the familiar and the unfamiliar.

In that moment I understood that an architect is much like a portrait painter. In their guild they learn their craft and its art by using materials, skills, techniques, and traditions, and like a portrait artist they must understand who their client is, all the while searching for that enriching disturbance. So now I can write, “Architecture is the portrait of its client”.

Somehow I find myself with a memory from thirty years ago. I was in a course where I discovered the power of trust, the trust that was needed for collaborative effort to succeed. The trust that Marianne and Heloise needed for the portrait to come alive. And it was here that I first heard someone say, “The journey is more important than the destination”.

A creative mind is restless, perpetually bouncing between self-doubt and satisfaction. There is pain in creating, and pleasure in the achievement. In private it searches for pure self - expression, in public it seeks acceptance. To progress, as Le Corbusier mused, “you must burn what you love”.

Some time after Marianne finished the portrait of Heloise, she made a painting of her alight with fire, perhaps to clear her mind of the memory of Heloise. In a creative mind the fire always burns, there is no choice. While the flames flicker at times and rage at others, they burn the past to create space for the future. Hopefully among the ashes there are some relics that make the world a better place for a lucky few.