Bunker-like houses on small blocks are robbing our streets of their dignity.

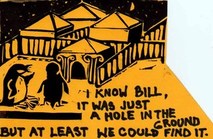

Cartoon by Natasha Williams-Novak

Cartoon by Natasha Williams-Novak By Tim Shannon

LOOKING around the emerging conglomerations of houses on display in their new and naked maze of streets, do you wonder who is about to move into the home of their dreams? What adventures lie ahead for these infant neighbourhoods, these seedling communities? Why did they make this choice? What do the surrounding established neighbourhoods think about these interlopers? What is happening to the seemingly diminishing supply of farm land and bush land that is surrendered to these new settlers? Why do these new establishments seem to be monotonous clones of themselves? Should living near the coast reveal itself as being different from living inland?

To date, I have lived in 20 houses, in three countries, in five cities and two regional coastal towns. So, I have lived on 20 varying kinds of streets and in 20 different neighbourhoods. Perhaps my most valuable memories and forgotten experiences are mysteriously embedded in those places. The houses we live in connect us with family and friends, with the sky, the sun and the moon, the winds, the clouds and the rain. They provide the theatre for our daily lives, they tell the story of who we are. They become the touchstones of our memories. In these ways, they also shape our feelings about what we believe a house should be.

We also develop aspirations to live in a particular place, a type of street, a style of house. Along the way, we learn the things that really matter are more about feeling safe and comfortable, being private when we want or need to be, enjoying the familiarity of knowing neighbours and being known by neighbours, and the pleasure of “coming home” at day’s end or after a holiday, and the sadness of having to move on.

It is the generosity of the street that really makes this possible. It sets out clearly what is public and for all to enjoy and care for, the verge. It provides the boundary between public and private, the front fence. It provides a place to show off and be proud of, where conversations with neighbours can be had on safe ground, the front garden. Complete privacy and personal expression is offered by the house, while the back yard is where folk can let their hair down.

It is just some 200 years since settlers began to ruin the land that they had sailed to and went about subjecting to their needs, building streets, houses, and amenity for their communities. Our settlements are really very young, and a long way yet from harbouring the myriad of memories and stories of their archetypes in distant nations. We have enjoyed an endless supply of land for generations, but now find that farming is not what it used to be, and climate scientists tell us that our addiction to open spaces has resulted in our people being among the world’s highest producers of carbon emissions.

So we find ourselves now challenged with trying to accommodate more people on less land, trying to conserve and reuse resources and energy, and trying to reduce the infrastructure sprawl and inefficiencies that we have grown up with. There is a residential development in Cowes which won design awards for its ground-breaking sustainable initiatives some 10 years ago, and has set a benchmark for its successors. Do you, like me, wonder if in the generations ahead, it, and estates like it, will be places of treasured memories and experiences for the communities that live out their lives in its houses and its all-important streets? Have we lost touch with what matters most, have we stopped placing value on the intangible, unmeasurable comfort and pleasure of being at home?

There was a time not that long ago when our parents’ new houses could not be bigger than 12 “squares”, 120 square metres. Today the starting point seems to be an expectation of at least double this size.

The desire to claim land and hold ownership of it has resulted in “blocks” for living on becoming smaller. Thus they become more affordable, and can accommodate more folk with more efficient use of resources. But the desire for luxury and comfort has resulted in houses becoming larger and larger.

As I look around the emerging neighbourhoods, I see that now that the “parlour” or “front room” is a fish bowl in the street; that the means of distinction between houses is the treatment of the double garage and the motor car parked on the wide abrupt driveway; that houses press up against fences on their sides and backs so windows have no outlook to enjoy; and that street layouts ignore the difference between fronts, backs, and sides. The houses on their blocks have become refuge bunkers, and their facades in the street create a Hollywood stage set.

So the house has changed; but people buy them and live in them, there is constant demand for them, and developers take the risk of continuing to build them in the hope that people will want to buy more of them. However, the street has also changed. It no longer has a clearly defined public verge, a front fence to announce the boundary of public and private, and the semi-private garden that allows the safe transition into the privacy and comfort of “home”. All life on the street is now utterly naked and one-dimensional. The subtleties of “going out” and “coming home”; of tending the front garden; of a chat with a neighbour over the front fence; of pets and children playing safely and happily behind the front fence; of collecting the morning paper and putting out the rubbish, they are all gone, and gone with them are the possibilities of fond memories.

Also gone is the individuality and character of the streets. They are all the same random collection of wide concrete driveways, garage doors, narrow footpaths, and mean setbacks to the monotonous drone of the jumbled houses that huddle along their winding and confusing thoroughfares. Yes, they look after storm water management and water retention; yes, they accommodate six star energy rated houses; yes, they accommodate more people in affordable housing; and no, they do not have overhead power and phone lines. These are the same streets that were judged to be design award winning, and I suspect that those judges do not live in streets like these.

My lament is that the streets have been robbed of their dignity and, in doing so, the neighbourhoods that they serve are also robbed of opportunities to offer their communities the fond memories that enrich our lives.

Professor Tim Shannon is a Fellow of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects, an architect and urban designer. He has a holiday house at Ventnor.

COMMENTS

December 7, 2014

Thanks, Tim, for your thought-provoking article on the homogenous big boxes on little blocks that keep pushing out into our “ever-diminishing supply of farmland and bushland”'. And thanks, Natasha, for another cartoon that captures the point so succinctly.

New housing developments have always looked ugly until they become softened with greenery. But when houses cover most of the block, there's no room to grow a tree or even a few shrubs. With no shade in summer, no wonder every house “'needs”' an air-conditioner. Bigger houses cost more (to the occupants and the environment) to heat and cool. As each new cloned housing estate eats into the landscape, it takes another bite out of the uniqueness of our coast.

Linda Cuttriss, Ventnor

December 6, 2014

Yes Tim Shannon; I agree. Considering the ugly small-site development becoming common in South Gippsland, I would add that well designed low-rise apartment buildings (2 - 4 stories) offer clearly better aesthetic and social values than the small units mushrooming around us on tiny 'unit' blocks.

There is no reason why Bass Coast Council shouldn't create incentives to stimulate appropriate apartment development in towns such as Wonthaggi and Inverloch.

Michelle Nelson, Wonthaggi

December 6, 2014

Tim, I really enjoyed your commentary on the role of different zones of a house on a block and especially the discussion on the ambiguity of a fenceless front garden. Thanks.

Liz Low www.lizsenseofplaces.com

December 6, 2014

I too lament the passing of the typical and unique Australian suburban house with its individuality, privacy, green space, front garden and family friendly back yard. No longer will the streetscape have individuality in housing or front garden design. The welcome sound of healthy children playing back yard touch and run cricket, or footy, is lost, as private open space shrinks to be replaced by the mind and communication destroying addiction to computer games and TV viewing.

Why is it so. One could point to the changing pattern and demands of society. The lack of personal time to create and lovingly tend a garden. The advent of technology replacing the need for creativity in a physical sense. The cost of housing, land and commuting, in our ever expanding cities.

Are these changes forced onto us by circumstances beyond our control, or are they compounded by planning inadequacies, the lack of political will to consider quality of life above the economic demands of development.

Australia is in a unique position with the space to plan urban development to maintain and improve our quality of life. The endless expansion of the major cities is a shortsighted, knee jerk, unconsidered response to population increase, country to city migration, city centric planning and the total lack of Government vision and support for decentralization.

As cities relentlessly expand without restriction, not only does the quality of life and the opportunity for reclaiming our unique Australian suburban house and outdoor lifestyle diminish. the cost of living and commuting increase at the expense of arable farming land being destroyed by the urban sprawl.

The time to reassess our direction, and act, is now.

Ian Samuel, Ventnor-Cowes

LOOKING around the emerging conglomerations of houses on display in their new and naked maze of streets, do you wonder who is about to move into the home of their dreams? What adventures lie ahead for these infant neighbourhoods, these seedling communities? Why did they make this choice? What do the surrounding established neighbourhoods think about these interlopers? What is happening to the seemingly diminishing supply of farm land and bush land that is surrendered to these new settlers? Why do these new establishments seem to be monotonous clones of themselves? Should living near the coast reveal itself as being different from living inland?

To date, I have lived in 20 houses, in three countries, in five cities and two regional coastal towns. So, I have lived on 20 varying kinds of streets and in 20 different neighbourhoods. Perhaps my most valuable memories and forgotten experiences are mysteriously embedded in those places. The houses we live in connect us with family and friends, with the sky, the sun and the moon, the winds, the clouds and the rain. They provide the theatre for our daily lives, they tell the story of who we are. They become the touchstones of our memories. In these ways, they also shape our feelings about what we believe a house should be.

We also develop aspirations to live in a particular place, a type of street, a style of house. Along the way, we learn the things that really matter are more about feeling safe and comfortable, being private when we want or need to be, enjoying the familiarity of knowing neighbours and being known by neighbours, and the pleasure of “coming home” at day’s end or after a holiday, and the sadness of having to move on.

It is the generosity of the street that really makes this possible. It sets out clearly what is public and for all to enjoy and care for, the verge. It provides the boundary between public and private, the front fence. It provides a place to show off and be proud of, where conversations with neighbours can be had on safe ground, the front garden. Complete privacy and personal expression is offered by the house, while the back yard is where folk can let their hair down.

It is just some 200 years since settlers began to ruin the land that they had sailed to and went about subjecting to their needs, building streets, houses, and amenity for their communities. Our settlements are really very young, and a long way yet from harbouring the myriad of memories and stories of their archetypes in distant nations. We have enjoyed an endless supply of land for generations, but now find that farming is not what it used to be, and climate scientists tell us that our addiction to open spaces has resulted in our people being among the world’s highest producers of carbon emissions.

So we find ourselves now challenged with trying to accommodate more people on less land, trying to conserve and reuse resources and energy, and trying to reduce the infrastructure sprawl and inefficiencies that we have grown up with. There is a residential development in Cowes which won design awards for its ground-breaking sustainable initiatives some 10 years ago, and has set a benchmark for its successors. Do you, like me, wonder if in the generations ahead, it, and estates like it, will be places of treasured memories and experiences for the communities that live out their lives in its houses and its all-important streets? Have we lost touch with what matters most, have we stopped placing value on the intangible, unmeasurable comfort and pleasure of being at home?

There was a time not that long ago when our parents’ new houses could not be bigger than 12 “squares”, 120 square metres. Today the starting point seems to be an expectation of at least double this size.

The desire to claim land and hold ownership of it has resulted in “blocks” for living on becoming smaller. Thus they become more affordable, and can accommodate more folk with more efficient use of resources. But the desire for luxury and comfort has resulted in houses becoming larger and larger.

As I look around the emerging neighbourhoods, I see that now that the “parlour” or “front room” is a fish bowl in the street; that the means of distinction between houses is the treatment of the double garage and the motor car parked on the wide abrupt driveway; that houses press up against fences on their sides and backs so windows have no outlook to enjoy; and that street layouts ignore the difference between fronts, backs, and sides. The houses on their blocks have become refuge bunkers, and their facades in the street create a Hollywood stage set.

So the house has changed; but people buy them and live in them, there is constant demand for them, and developers take the risk of continuing to build them in the hope that people will want to buy more of them. However, the street has also changed. It no longer has a clearly defined public verge, a front fence to announce the boundary of public and private, and the semi-private garden that allows the safe transition into the privacy and comfort of “home”. All life on the street is now utterly naked and one-dimensional. The subtleties of “going out” and “coming home”; of tending the front garden; of a chat with a neighbour over the front fence; of pets and children playing safely and happily behind the front fence; of collecting the morning paper and putting out the rubbish, they are all gone, and gone with them are the possibilities of fond memories.

Also gone is the individuality and character of the streets. They are all the same random collection of wide concrete driveways, garage doors, narrow footpaths, and mean setbacks to the monotonous drone of the jumbled houses that huddle along their winding and confusing thoroughfares. Yes, they look after storm water management and water retention; yes, they accommodate six star energy rated houses; yes, they accommodate more people in affordable housing; and no, they do not have overhead power and phone lines. These are the same streets that were judged to be design award winning, and I suspect that those judges do not live in streets like these.

My lament is that the streets have been robbed of their dignity and, in doing so, the neighbourhoods that they serve are also robbed of opportunities to offer their communities the fond memories that enrich our lives.

Professor Tim Shannon is a Fellow of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects, an architect and urban designer. He has a holiday house at Ventnor.

COMMENTS

December 7, 2014

Thanks, Tim, for your thought-provoking article on the homogenous big boxes on little blocks that keep pushing out into our “ever-diminishing supply of farmland and bushland”'. And thanks, Natasha, for another cartoon that captures the point so succinctly.

New housing developments have always looked ugly until they become softened with greenery. But when houses cover most of the block, there's no room to grow a tree or even a few shrubs. With no shade in summer, no wonder every house “'needs”' an air-conditioner. Bigger houses cost more (to the occupants and the environment) to heat and cool. As each new cloned housing estate eats into the landscape, it takes another bite out of the uniqueness of our coast.

Linda Cuttriss, Ventnor

December 6, 2014

Yes Tim Shannon; I agree. Considering the ugly small-site development becoming common in South Gippsland, I would add that well designed low-rise apartment buildings (2 - 4 stories) offer clearly better aesthetic and social values than the small units mushrooming around us on tiny 'unit' blocks.

There is no reason why Bass Coast Council shouldn't create incentives to stimulate appropriate apartment development in towns such as Wonthaggi and Inverloch.

Michelle Nelson, Wonthaggi

December 6, 2014

Tim, I really enjoyed your commentary on the role of different zones of a house on a block and especially the discussion on the ambiguity of a fenceless front garden. Thanks.

Liz Low www.lizsenseofplaces.com

December 6, 2014

I too lament the passing of the typical and unique Australian suburban house with its individuality, privacy, green space, front garden and family friendly back yard. No longer will the streetscape have individuality in housing or front garden design. The welcome sound of healthy children playing back yard touch and run cricket, or footy, is lost, as private open space shrinks to be replaced by the mind and communication destroying addiction to computer games and TV viewing.

Why is it so. One could point to the changing pattern and demands of society. The lack of personal time to create and lovingly tend a garden. The advent of technology replacing the need for creativity in a physical sense. The cost of housing, land and commuting, in our ever expanding cities.

Are these changes forced onto us by circumstances beyond our control, or are they compounded by planning inadequacies, the lack of political will to consider quality of life above the economic demands of development.

Australia is in a unique position with the space to plan urban development to maintain and improve our quality of life. The endless expansion of the major cities is a shortsighted, knee jerk, unconsidered response to population increase, country to city migration, city centric planning and the total lack of Government vision and support for decentralization.

As cities relentlessly expand without restriction, not only does the quality of life and the opportunity for reclaiming our unique Australian suburban house and outdoor lifestyle diminish. the cost of living and commuting increase at the expense of arable farming land being destroyed by the urban sprawl.

The time to reassess our direction, and act, is now.

Ian Samuel, Ventnor-Cowes