THE first time my family visited Phillip Island on a hot and windy summer day 30 years ago, we found a rough unkempt place, where perhaps we felt unwelcome.

Nevertheless, our love of the beach kept drawing us back, and our love/hate relationship with the Island grew into one of respect and admiration.

Today, we are grateful for all the rewarding experiences the Island has offered us, even though we are still outsiders.

So I was very pleased to be asked to think about contemporary art and architecture being a celebration of the history and culture of the Bass Coast Islands.

I hope my meanderings will entertain you a little.

In times past, the Bunurong members of the Kulin Nation walked on land that would become French Island, Phillip Island, and Churchill Island before the sea rose to create Western Port Bay.

They also walked from San Remo to Newhaven, when Phillip Island was still a peninsula, just five or six thousand years ago.

Their visits were guided by the seasons, and it was largely the beaches that sustained them. Their culture relies on two simple beliefs: caring for their land, and caring for their children. And so it was on the Islands of Western Port.

Islands are places of fascination, and inspiration for stories of treasure, desertion, paradise, and refuge.

They are the subject of research by anthropologists, sociologists, and geographers, whose work tells us that the evolving culture of Island societies is strongly influenced by the way they were first inhabited by man.

What good fortune that the Bunurong people cared for the Western Port and its Islands for many thousands of years.

Since Europeans first appeared, these Islands have had a chequered history. More than 220 years ago hunters were plundering the seal colonies and causing irreparable harm to the Bunurong people.

The French and the English were tussling over global supremacy, and in 1801 the English claimed ownership of Western Port by planting some wheat and building a wooden slab hut on Churchill Island.

For this, they happened to choose a stand of ancient Moonah trees that was sacred to the Bunurong people.

The crop failed, the hut fell apart, and the Europeans left the Islands alone.

Forty years later, two McHaffie brothers arrived from Melbourne and took up a squatter’s lease on Phillip Island to graze sheep.

For the next 28 years, in Scottish tradition, their isolated settlement “resisted dynamic progress created by the gold rush and the many luxuries and trends of architecture”*.

And so we arrive at 1868, the 150 year anniversary that we are celebrating today.

It was the year John King was rescued by Aborigines at the Dig Tree after the demise of the infamous Burke and Wills expedition, it was near the height of Melbourne’s gold rush boom, and it was the year the colourful colonist Dr Louis Lawrence Smith finally succeeded with his desire to offer settlers the opportunity to live an ideal life on a model farm, on Phillip and Churchill islands.

The Surveyor General drew a patchwork plan that covered the islands with rectangular farm allotments varying in size from 80 to 300 or so acres (30-120 hectares) each. The plan made little acknowledgement of topography, aspect, soil, water, or vegetation.

It created a tension between the allotment size, location, and productivity which has lasted until today.

132 lots were sold by ballot in the first land sale, so ending McHaffie’s lease, and offering the hopeful settlers the opportunity to start a new life on their model farms.

The Island may have suited the McHaffie’s grazing needs, but it proved to be mostly unsuitable for crop farming, so causing considerable distress.

However, the friendship between Dr Smith and Baron Von Mueller, the famous botanist, led to Von Mueller suggesting the planting of mustard and chicory crops. Thanks to chicory, many of the Island’s farmers were able to earn a hard living for a hundred years.

Thus began the process of converting much of the Island’s landscape into the picturesque rolling fields and paddocks we know today, completing the palette of natural coast line and man-made farmland which has become the setting for the contemporary settlement of the Island.

Today, French Island is a reminder of what might happen when the competition for private ownership is kept at bay and access is limited.

Churchill Island is a reminder of what Dr Smith’s perfect model farm might look like, and Phillip Island is living testament to a democratic ideal played out on a finite, beautiful, treasure island.

We might say that the culture of Phillip Island has been shaped by isolation, hardship, and the camaraderie of the people who took the chance they were offered.

It enjoys a spirit of freedom, is suspicious of external interference, and is proudly self- reliant.

It has been enriched by the history and natural beauty of the Island, and it continues to acknowledge its obligation to protect this for future generations.

This culture is reflected in its buildings.

They have a vernacular of purpose and toughness, “touching the ground lightly” to bring a smile to the Bunurong people.

According to Vitruvius, the ancient Roman scholar, firmness and commodity are not enough; architecture must also be a source of delight.

The chicory kilns standing today like sentinels around the Island are pure buildings crafted to perform, they are firm and functional.

Their delight comes from the contribution they make to the memory palace that Phillip Island is, they tell of a united community’s century of toil and reward.

The desire to live on an Island has attracted all sorts of folk who have made for themselves all sorts of homes from mansions and guest houses to shacks and caravans.

Here lies the heart of the Island’s architecture, where houses provide delight to their owners. Hidden away like pearls, delighting their owners, understated houses dot the Island with their rich memories.

Peter Maddison’s house at Surf Beach is a fine example of the simple upside down pole house. This pragmatic and efficient no-fuss type of house is sprinkled around the Island without fanfare, and has been the source of endless happy family holidays.

Barry Marshall’s house at Kitty Miller Bay is the ultimate reclusive house; buried in its stunning but tough landscape, it is invisible, the perfect sanctuary.

Not everyone can afford the luxury of a beach house, or ten acres of foreshore scrub to hide away in.

New housing estates might not be what Dr Louis Lawrence Smith had in mind, but they are reminiscent of his desire to make squatters’ land available to a greater number of families. They are a continuation of suburbia, offering affordable Island homes to thousands of new settlers, which is, after all, a generous thing.

They have also galvanised the Island community to fix the town boundaries to contain the loss of farm and coastal land.

Maybe this has been a win for new settlers and a win for the Island; either way, it has been a big win for homes builders and suppliers.

In the last 50 years, the motel has taken over from the guest house, the supermarket from the corner store, the aged care home from the cinema.

The caravan park makes way for apartments and town houses, and the hardware store has become an industrial estate.

Carparks bulge in summer and are empty in winter.

The ice cream kiosk has become a visitor experience centre. The cafe is a restaurant.

The pub is a micro- brewery. The coffee shop is a wine bar.

The main street is a theme park in summer and a stage set in winter. This is the story of many coastal towns.

Step out of these places, and Phillip Island has endless delights and experiences to nourish the curiosity and souls of generations to come.

Its architecture is to be found in its beaches, mangroves, and farmlands.

The Bunurong people were right to come and go with the seasons, and the McHaffies were right to shun Melbourne.

The early settlers were right to touch the ground lightly.

They all let the Island beauty speak with the loudest voice; it does not need or want the distractions of ostentation and sophistication.

There is no need for its buildings to compete with its natural beauty, they just need to show respect.

And what of Art, you ask?

Two thousand four hundred years ago, Aristophanes posed the question, “What do you want a poet for?”, and answered it thus, “To save the City, of course”.

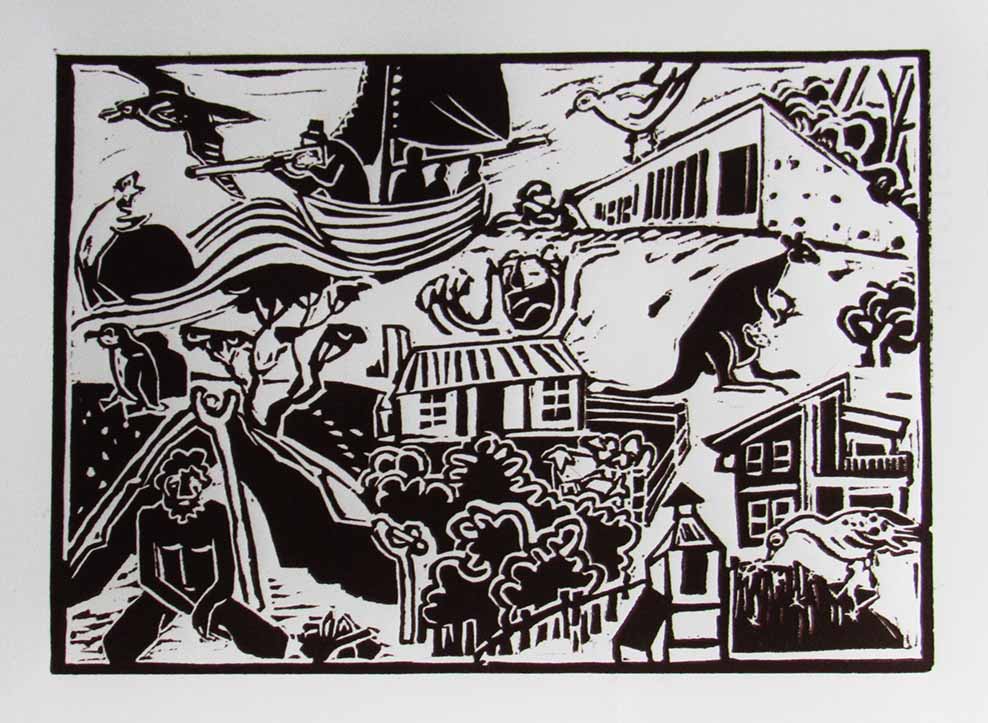

Phillip Island attracts poets, and writers, and musicians; and artists.

The common theme of why they choose to be here is the underlying sense of rich history, and the eternal attraction of the coast.

There is also mention of the calm, the passing of the seasons, cloudy skies on windy days, the wildlife, the moods of the sea, and the passing of the sun, the moon, and the stars.

Regardless of their medium, subject, or expression, or whether their interest lies in the figure, the landscape or abstraction, they say it is the Island that sustains them.

Josephine Kent, an artist who has worked on Phillip Island since 1980, says you need to look among the tea trees to find the artists here. They are many and private, their community is strong, and they raise their voices when the beauty of the Island is threatened.

Among the many artists who have come here over the years, her remarkable list includes Eugene von Guerard, Frederick Mc Cubbin, Walter Withers, Inge King, John Olsen, Eric Juckert, Reg Langslow, Jason Monet, David Fincher, Russell Kent, Josephine Kent, Janet Bodaan, Victoria Nelson, Bill Binks, Robert Ingpen, Robert Wade, John Canning, Patsy Hunt, Silva and Deborah Halpern, Jane Flowers, Lynne Chandler, Ricky Swallow, John Adam, Camille Monet, Joy Hazel, Peter Walker, Marian Quigley, and Diana Edwards.

These people are our conscience; through their work and presence, they truly celebrate and “save” the Island.

This seems like the perfect time to return to the Bunurong people, and their culture of caring for the land and for their children. Surely, these two principles are the basis of any sustainable society.

The Islands of Western Port have a long history of wrestling with these aspirations. There have been successes and failures. On balance, the record today is in favour of success.

There are two contemporary examples that deserve celebration. The first is about caring for the land.

Establishing the Phillip Island Nature Parks in 1996 and charging it with responsibility for caring for much of the natural resources of Phillip Island has been a master stroke.

The Summerland “buy back” is one of the most remarkable conservation stories in Australia. While there is a commercial consideration in terms of the tourist attraction of the penguins, it has successfully raised the profile of nature conservation on the Island, which will absolutely encourage care for the land.

The second is about caring for the children.

The voluntary work of the Vietnam veterans over the last thirty years, culminating in the building of the National Vietnam Veterans Museum, is an amazing achievement.

Motivated by the desire to tell the story of the veterans, not to dwell on the war, but to give the veterans a chance to be heard, and to heal, the siting of the museum on Phillip Island is perfect.

In a distant corner of the continent, in the calm and beauty of Western Port sheltered from the storms of Bass Strait, all visitors making the pilgrimage are welcome.

This achievement is in the tradition of the self-reliant, no-frills ways of the early settlers. The building is pure and efficient, it is the work of volunteers.

Its memories are profound, and, like the most powerful of architectural achievements, it can make the hairs on the back of your neck stand up and stir tears of emotion.

Our children are lucky to have this story told so well, and perhaps they will help to prevent history repeating itself.

Still an outsider, it seems to me the Islands of Western Port have been blessed with a great array of natural beauty.

Their relative remoteness and sometimes rugged weather have helped them to navigate their way through the last two hundred years of European settlement.

In this 150 year celebration, it is the Islands that are the heroines.

We trust that future generations will learn from the past, and continue to care for the beautiful land that will only become more precious.

References

- Anderson, K. “Soldiers are Persons”, NVVM Ltd, 2011.

- *. Evans, Cargill and Evans, “Architectural History of Phillip Island to Commemorate the Centenary of Open Settlement on Phillip Island”, University of Melbourne, 1968.

- Centre for Environmental Studies, University of Melbourne, “Phillip Island, Capability, Conflict, and Compromise”, 1975.

- Chamberlain, J.E. “Island: How Islands Transform the World”, Blue Bridge, 2013.

- Gaughwin, D. “Sites of Archaeological Significance in The Western Port Catchment”, Ministry for Conservation, 1981.

- Giddon, J.W. “Phillip Island in Picture and Story”, Wilke and Co.,1968. Phillip Island and District Historical Society, “Phillip Island History”, 2016.

- Poynter, J. “The Audacious Adventures of Dr Louis Lawrence Smith”, Australian Scholarly Publishing Pty Ltd, 2014.

Consultation

My thanks to the following people for generously providing valuable background advice and information:

- Greg Buchanan, President, Bass Coast Branch of The National Trust of Australia. Phillip Island residents Gaye Cleeland, Julie Box, John Jansson, and Anne Davie.

- Phillip Island artists Natasha Williams, Luciano Prisco, Marian Quigley, and Josephine Kent. Phil Dressing, General Manager, National Vietnam Veterans Museum, Phillip Island.

Tim Shannon’s essay was written at the invitation of the Bass Coast Branch of the National Trust of Australia, on the 150th anniversary of the1868 free selection of Phillip Island land. He was asked to explore how contemporary art and building design celebrate the culture, history and environment of the islands of Westernport.