FRED Hollows, the New Zealand/Australian ophthalmologist famous for his work in restoring eyesight to thousands of people around the world, and especially to the indigenous people of Australia, was a fan of the author Michael Ondaatje. I recall reading a newspaper article about how angry Fred was when his life was ending and he realised he would not be afforded the time to finish reading The English Patient, Ondaadje's most famous novel.

The news item has stayed with me, not just because of my admiration for Fred Hollows but also because of Ondaatje, my favourite writer. His novel In the Skin of a Lion, written five years earlier, is at the top of my list. Part of the reason is that, as one reviewer put it, "... it is a poem to workers and lovers".

Ondaatje took the title for his book from a passage in The Epic of Gilgamesh: "The joyful will stoop with sorrow, and when you have gone to the earth I will let my hair grow long for your sake, I will wander through the wilderness in the skin of a lion."

Very early in the book Ondaatje tells about a young farm boy watching in the faint dawn light as thirty itinerant loggers carrying lanterns move to the side of the road in hushed politeness to let cows move from pasture to barn for milking. "Sometimes the men put their hands on the warm flanks of these animals and receive their heat as they pass by."

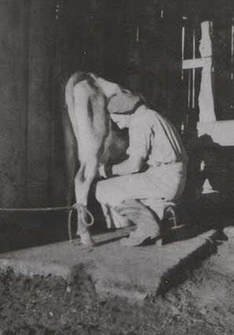

I, too, know that feeling. In my early years I had to rouse cows in the morning darkness, gathering and herding them in their silent protest towards the cow shed. I was assigned the ones that had to be hand milked and was grateful for their warmth on those cold mornings as I rested my head on their flank and enticed them to let down their milk.

Now, after a life time spent elsewhere, I find myself settled down in country inhabited by herds of dairy cows, fields dotted with bales of silage wrapped in plastic coats the colours of the rainbow, disused butter factories or their ruins as I pass through places like Archie's Creek, Kongwak and, on a first recent visit, Glengarry.

I know this is a bit of a stretch but what has prompted these thoughts and memories of my fleeting affair with the dairy industry is the sad news that the once all-powerful Murray Goulburn Co-operative Company is teetering on the edge of oblivion. Due to cut-throat competition, milk prices, commercial performance and other complex issues beyond my ken it now has a binding agreement to sell out to Saputo, the Canadian dairy giant. We are saying goodbye to a company that is 100 per cent controlled by its dairy farmer suppliers and that operates under co-operative principles.

The co-operative commissioned Catherine Watson to research and record their history and her book Just a Bunch of Cow Cockies was published in 2000. The title was inspired by one of the 100-plus interviews she conducted during her research. Jim Gemmell, the founding chairman, said "You know, we were as rough as guts when we started out. We were just a bunch of cow cockies who did our best. But look at what we have now!”

Catherine relates a story from their formative days of a meeting held at the Cobram factory. A delegation from the Kraft head office in Melbourne had travelled down to remind the Murray Valley company (as it was known then) that it was set up as a cheese factory and should not be supplying whole milk. After discussing the matter, the Murray Valley directors told them they would adhere to their city milk contracts. That didn’t go down well with the men from Kraft, and their spokesman replied "We’re very sorry that’s your decision, but I have to tell you we'll break you if we can."

It used to be said that the co-operative was bound to succeed because the directors were too pig-headed to know when they were licked.

Ordinary men and women representing ordinary farmers, sticking together.

The cover of the book pictures a lone milkman hand milking in an old lean-to shed. And I think hey! that looks like me.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed