In the wake of this week's demolition of Wonthaggi's old co-op bakery, CAROLYN LANDON reflects on the role of the co-operative movement - and the bakery - in the former coal mining town.

IN ENGLAND, Robert Owen (1771-1858), a utopian socialist and social reformer, was the father of the co-operative movement, which was, for our purposes in this article, a partnership among employees for social and economic wellbeing. The co-operative movement was popular in coal-mining communities in England, Scotland and Wales in the late 19th Century. When the opening of the State Coal Mine coincided with an influx of workers from northern England and Scotland and the establishment of the Wonthaggi township, the idea of setting up a co-operative was in the air.

Early attempts to establish co-ops in older mines in Jumbunna and Outtrim had failed, partly because they were privately run mines, but perhaps more importantly because they did not have charismatic characters like Matt McMahon to make them succeed. McMahon was a political thinker and an idealist who could enter a room and clarify any confusion about issues of democracy, constitution, collective decision-making and social justice to the satisfaction of all parties.

McMahon and several other miners – plus townspeople – attempted to get a co-operative going as early as 1910, but it was not until 1912 that there was the right climate – a new town with a self-help, can-do ethos and democratic ideals combined with workers fresh from the Rutherglen, Creswick, Allandale and Ballarat gold mines – to take the ideas of co-operativism and make them work.

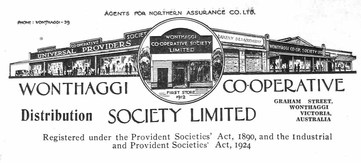

Since, the ideal was for co-ownership of any enterprise, anyone who wanted to become a member of the Wonthaggi Co-operative had to become a shareholder and was required to maintain a minimum shareholding of £5, which could be bought on a subscription system at two shillings and sixpence per fortnight. By late 1912 there was enough support for the co-op to commence trading from its first premises in Watt Street. As the co-op grew, it had to be shifted to larger premises on Graham Street in 1918.

Before it was torn down and rebuilt to house the expanding bakery connected to the co-op, the building at Watt Street was probably used to stable the horses that pulled the carts to deliver goods to homes throughout Wonthaggi. After John Short took over as manager of the co-op, the boom years started and expansion was the word. Under the guidance of Short, in 1925 the co-op employed Collins Street architect Harry A. Norris to re-design the Graham Street shop (with the remarkable inclusion of a cool store), and at the same time design a new bakehouse to be erected across the lane at the back of the co-op building on the original premises at Watt Street.

The bakehouse was built by Mr Frongerude, a Norwegian man (who, tragically, was later drowned with his whole family in Inverloch). Mr Frongerude, who was a master builder and perfectionist, was also responsible for building the Railway Station, the Post Office, the State Bank and other public buildings in Wonthaggi. It is known that he salvaged and used the bricks from the original building at Watt Street in the new building. The bakehouse was ready for use in 1926.

Naturally, whenever anyone mentions the old Bakehouse, memories begin to stir. Sam Gatto, who arrived here as a small boy in the early 1950s, says his first memory of Australia was the smell of carnations and the second was the smell of baking bread coming from the co-op bakehouse. Unfortunately, his proudly Italian mother would never buy the bread since she insisted hers was much better. Poor Sam.

Once you begin remembering the bread, you recall the bakers and the carters and the tokens and, of course the co-operative, itself. Everyone called it The Co. “You could get everything through The Co,” people used to say. “You could get buried through the Co!”

We know from documents in the files at the Railway Station Museum that you could buy pies and cakes for eight pence, cash, over the counter at the co-operative bakery. Much more impressive was that you could get a four-pound loaf of fresh baked bread delivered for nine pence as long as you had bought your token for it in advance.

Tokens came in five sizes that you would leave out for the carter who delivered the bread to pick up and replace with the right loaf. Stamped on one side of the token was “Wonthaggi Co-op Bakery” and on the other side, depending on what you wanted, “Good for Small Loaf”, “Good for Large Loaf”, “Good for 1lb Loaf”, “Good for 2lb Loaf” or “Good for 4lb Loaf.” According to Tilo Junge, who wrote a study of the bread tokens, by the 1950s there seemed to be no reason for five tokens when the bread only came in three sizes, but five tokens there were.

Terri Allen remembers the bread being delivered when she was a kid in the 1950s. It came wrapped in waxed paper that had printed on it, “W.S.C. Quality Bread. Wholesome – Nutritious. A product of Wonthaggi Co-operative Distribution Society, Ltd. Wrapped for your protection! Sliced for Economy! Net Weight 1 1⁄2 lb.” Behind the black print was a beautiful design of yellow stalks of wheat.

The clip clop of the horse pulling the bread cart early in the morning was easy to mix up with the same sound of the grocery cart, the dairy cart or the iceman on his cart, but it was a sound familiar to all Wonthaggians right through the sixties. John Heywood’s dad was one of the bread carters. He kept his horse and cart at the back of the bakery and was a welcome sight around the town.

Some people had special bread tins or boxes for the loaves to be left in outside the back of the house. Others had kitchen dressers that had a special tin-lined drawer in them, and the bread man would bring the loaf right into the kitchen to put it away. Terri remembers that her mother kept their tokens in the casing of an old army shell and on bread day, she would leave a token on the ledge inside their back veranda for the carter to swap with a loaf. No one ever stole anyone’s bread, or the tokens, for that matter.

The old co-op bakery was demolished this week against the wishes of the Wonthaggi Historical Society.

Pies and cakes were eight pence, cash, over the counter at the co-operative bakery.

If you bought your token in advance, you could get a four-pound loaf of fresh baked bread delivered for nine pence.

The monthly co-op bill

Results of the annual co-op election

The co-op grocery delivery was something Terri remembers with delight. The fellow – Dommie Dobson was Terri’s favourite, but she remembers Mr Howell as well – would come into the kitchen each week and talk over the grocery list with the woman (usually) of the house, writing down each item in his book, if she hadn’t already made her list. Then, when he delivered, he would bring the groceries round the back to the kitchen and, if no one was home, he would put the perishables away for the housewife, no extra charge. He always left the carbide the miners used for their lamps outside. It came in a brown paper bag and had a distinct smell.

The co-op was an integral part of the fabric of Wonthaggi society and everyone you meet of a certain age has a story to tell. You could buy just about anything at The Co: shoes, milk, petrol out the back, ironmongery, clothes, furniture, all with a discount if you paid your monthly bill on time. You could even get your boots repaired and all your butchery done, too. The co-op used to call for tenders for dairies and butchers to supply members for a year. And then at the end of the year, you got your dividends, since each co-op member had to have shares. “Mum used to save her dividends to pay the rates,” said one man.

Terri remembers going into the shop on McBride Avenue to get broken biscuits. When she was a kid, the biscuits came in tins and you bought them by weight. If, after school, you happened to have three pence in your pocket, you could go in and ask for three pence worth of broken biscuits, which would be handed to you in a brown paper bag. If someone you knew was behind the counter, like Dommie Dobson for instance, they might even throw in a few bits of chocolate for a smile.

The co-op existed until Home Pride took over the bakery in the early 1960s and then Food Land was built in the early seventies. Wonthaggi was a unique and wonderful place partly because of the co-op. As Sam Gatto says, “The co-op saved this town.”

COMMENTS

July 5, 2014

Just been reading Carolyn Landon's story (June 28, 2014) and getting all nostalgic about the Wonthaggi Co-op. That's where mum worked till she got married. I remember it well as a little girl going shopping on fridays with my mum and grandma. I especially remember the smell of the freshly baked bread on our way home from visiting my grandparents on Sunday nights. Actually, come to think of it, my first job ever was in the haberdashery section of the co-op in summer holidays when I was about 15.

Carolyn Landon writes an excellent story. Thanks again for the memories. I've forwarded it to mum. I'm sure she'll love it too.

Linda Cuttriss, Phillip Island

Early attempts to establish co-ops in older mines in Jumbunna and Outtrim had failed, partly because they were privately run mines, but perhaps more importantly because they did not have charismatic characters like Matt McMahon to make them succeed. McMahon was a political thinker and an idealist who could enter a room and clarify any confusion about issues of democracy, constitution, collective decision-making and social justice to the satisfaction of all parties.

McMahon and several other miners – plus townspeople – attempted to get a co-operative going as early as 1910, but it was not until 1912 that there was the right climate – a new town with a self-help, can-do ethos and democratic ideals combined with workers fresh from the Rutherglen, Creswick, Allandale and Ballarat gold mines – to take the ideas of co-operativism and make them work.

Since, the ideal was for co-ownership of any enterprise, anyone who wanted to become a member of the Wonthaggi Co-operative had to become a shareholder and was required to maintain a minimum shareholding of £5, which could be bought on a subscription system at two shillings and sixpence per fortnight. By late 1912 there was enough support for the co-op to commence trading from its first premises in Watt Street. As the co-op grew, it had to be shifted to larger premises on Graham Street in 1918.

Before it was torn down and rebuilt to house the expanding bakery connected to the co-op, the building at Watt Street was probably used to stable the horses that pulled the carts to deliver goods to homes throughout Wonthaggi. After John Short took over as manager of the co-op, the boom years started and expansion was the word. Under the guidance of Short, in 1925 the co-op employed Collins Street architect Harry A. Norris to re-design the Graham Street shop (with the remarkable inclusion of a cool store), and at the same time design a new bakehouse to be erected across the lane at the back of the co-op building on the original premises at Watt Street.

The bakehouse was built by Mr Frongerude, a Norwegian man (who, tragically, was later drowned with his whole family in Inverloch). Mr Frongerude, who was a master builder and perfectionist, was also responsible for building the Railway Station, the Post Office, the State Bank and other public buildings in Wonthaggi. It is known that he salvaged and used the bricks from the original building at Watt Street in the new building. The bakehouse was ready for use in 1926.

Naturally, whenever anyone mentions the old Bakehouse, memories begin to stir. Sam Gatto, who arrived here as a small boy in the early 1950s, says his first memory of Australia was the smell of carnations and the second was the smell of baking bread coming from the co-op bakehouse. Unfortunately, his proudly Italian mother would never buy the bread since she insisted hers was much better. Poor Sam.

Once you begin remembering the bread, you recall the bakers and the carters and the tokens and, of course the co-operative, itself. Everyone called it The Co. “You could get everything through The Co,” people used to say. “You could get buried through the Co!”

We know from documents in the files at the Railway Station Museum that you could buy pies and cakes for eight pence, cash, over the counter at the co-operative bakery. Much more impressive was that you could get a four-pound loaf of fresh baked bread delivered for nine pence as long as you had bought your token for it in advance.

Tokens came in five sizes that you would leave out for the carter who delivered the bread to pick up and replace with the right loaf. Stamped on one side of the token was “Wonthaggi Co-op Bakery” and on the other side, depending on what you wanted, “Good for Small Loaf”, “Good for Large Loaf”, “Good for 1lb Loaf”, “Good for 2lb Loaf” or “Good for 4lb Loaf.” According to Tilo Junge, who wrote a study of the bread tokens, by the 1950s there seemed to be no reason for five tokens when the bread only came in three sizes, but five tokens there were.

Terri Allen remembers the bread being delivered when she was a kid in the 1950s. It came wrapped in waxed paper that had printed on it, “W.S.C. Quality Bread. Wholesome – Nutritious. A product of Wonthaggi Co-operative Distribution Society, Ltd. Wrapped for your protection! Sliced for Economy! Net Weight 1 1⁄2 lb.” Behind the black print was a beautiful design of yellow stalks of wheat.

The clip clop of the horse pulling the bread cart early in the morning was easy to mix up with the same sound of the grocery cart, the dairy cart or the iceman on his cart, but it was a sound familiar to all Wonthaggians right through the sixties. John Heywood’s dad was one of the bread carters. He kept his horse and cart at the back of the bakery and was a welcome sight around the town.

Some people had special bread tins or boxes for the loaves to be left in outside the back of the house. Others had kitchen dressers that had a special tin-lined drawer in them, and the bread man would bring the loaf right into the kitchen to put it away. Terri remembers that her mother kept their tokens in the casing of an old army shell and on bread day, she would leave a token on the ledge inside their back veranda for the carter to swap with a loaf. No one ever stole anyone’s bread, or the tokens, for that matter.

The old co-op bakery was demolished this week against the wishes of the Wonthaggi Historical Society.

Pies and cakes were eight pence, cash, over the counter at the co-operative bakery.

If you bought your token in advance, you could get a four-pound loaf of fresh baked bread delivered for nine pence.

The monthly co-op bill

Results of the annual co-op election

The co-op grocery delivery was something Terri remembers with delight. The fellow – Dommie Dobson was Terri’s favourite, but she remembers Mr Howell as well – would come into the kitchen each week and talk over the grocery list with the woman (usually) of the house, writing down each item in his book, if she hadn’t already made her list. Then, when he delivered, he would bring the groceries round the back to the kitchen and, if no one was home, he would put the perishables away for the housewife, no extra charge. He always left the carbide the miners used for their lamps outside. It came in a brown paper bag and had a distinct smell.

The co-op was an integral part of the fabric of Wonthaggi society and everyone you meet of a certain age has a story to tell. You could buy just about anything at The Co: shoes, milk, petrol out the back, ironmongery, clothes, furniture, all with a discount if you paid your monthly bill on time. You could even get your boots repaired and all your butchery done, too. The co-op used to call for tenders for dairies and butchers to supply members for a year. And then at the end of the year, you got your dividends, since each co-op member had to have shares. “Mum used to save her dividends to pay the rates,” said one man.

Terri remembers going into the shop on McBride Avenue to get broken biscuits. When she was a kid, the biscuits came in tins and you bought them by weight. If, after school, you happened to have three pence in your pocket, you could go in and ask for three pence worth of broken biscuits, which would be handed to you in a brown paper bag. If someone you knew was behind the counter, like Dommie Dobson for instance, they might even throw in a few bits of chocolate for a smile.

The co-op existed until Home Pride took over the bakery in the early 1960s and then Food Land was built in the early seventies. Wonthaggi was a unique and wonderful place partly because of the co-op. As Sam Gatto says, “The co-op saved this town.”

COMMENTS

July 5, 2014

Just been reading Carolyn Landon's story (June 28, 2014) and getting all nostalgic about the Wonthaggi Co-op. That's where mum worked till she got married. I remember it well as a little girl going shopping on fridays with my mum and grandma. I especially remember the smell of the freshly baked bread on our way home from visiting my grandparents on Sunday nights. Actually, come to think of it, my first job ever was in the haberdashery section of the co-op in summer holidays when I was about 15.

Carolyn Landon writes an excellent story. Thanks again for the memories. I've forwarded it to mum. I'm sure she'll love it too.

Linda Cuttriss, Phillip Island

RSS Feed

RSS Feed