In the early 70s about 40 per cent of Australia’s 12 million population was under 20. Some teachers still used corporal punishment. Kids could be humiliated in front of the whole class or school assembly. The poor, non-Anglos and those who weren’t good at sport or academia were regularly reminded of their social inferiority. It put some students off education for life.

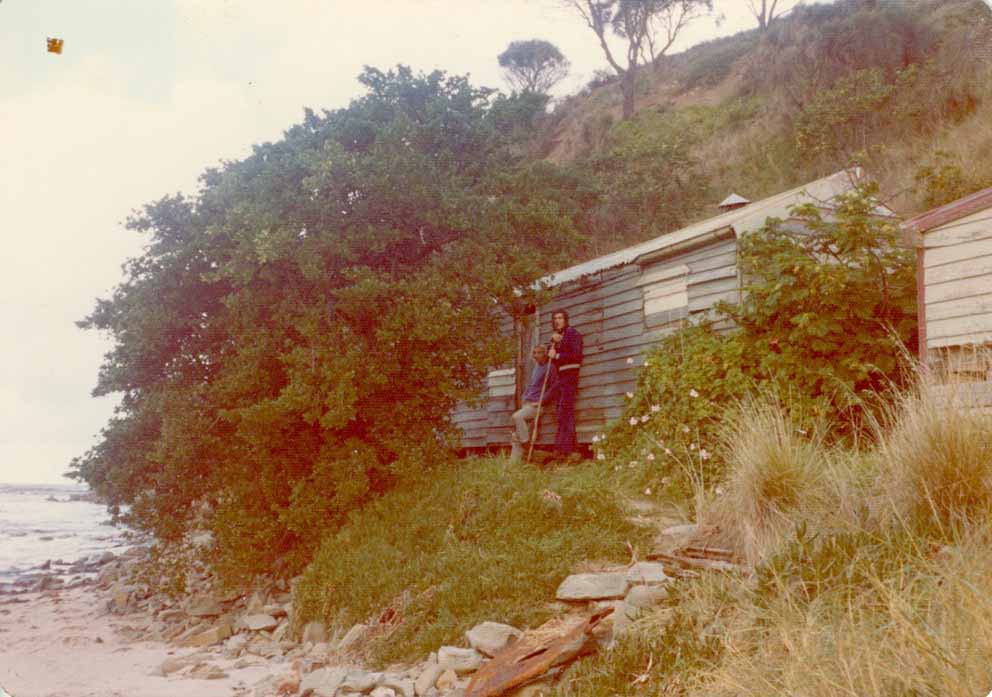

But American TV was starting to change the values, culture and tempo of Australia society. Kenny and Ronny ‘The Rat’ were gentle-souled refugees from a tough Melbourne where sharpie wars were still raging. They were lured to the Cape Paterson Surf Lifesaving Club by the promise of free weekend accommodation but couldn’t handle the military-style marching and drill of the club or the crash-through mentality of surf boat rowing.

The Channel camp expanded. In winter a fire was kept going to warm numb hands after a surf. The area began to look like the day after Woodstock. One Sunday morning Dave Cook, the caretaker at Cape, came with two policemen and told everyone they had to leave because the council was going to build a caravan park (now the Illawong Caravan Park).

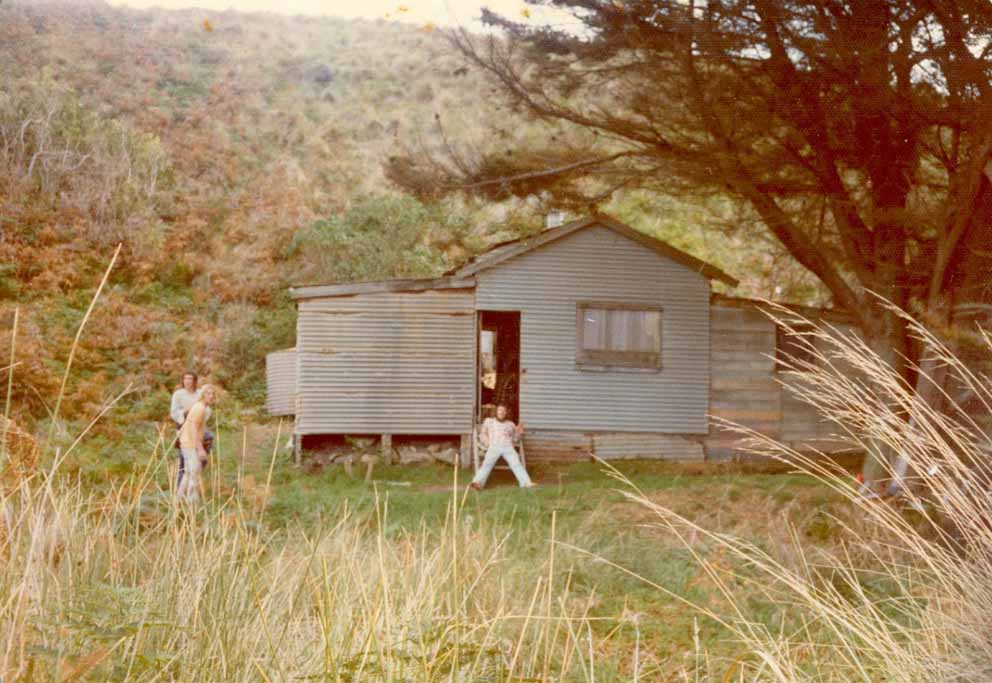

Some of the free campers decamped to secluded banksia woodlands near Harmers Haven and Cutlers Beach. Ron, Ken, and the Kavanagh and Sherrin Bros piled their stuff into an old ute and retreated to what was then remote Shack Bay. The unmade coast road then was a narrow track – longer, windier and very rough, with deep rabbit and wombat holes.

Hidden from the road, with a view of the sun and moon rise, Shack Bay had a serenity that absorbed its inhabitants. The bay wrapped around us and egos fell away in the face of nature’s beauty.

Just north of the huts, on a cleared north-east-facing slope, there was evidence of long abandoned vegetable plots probably hand-watered from the creek.

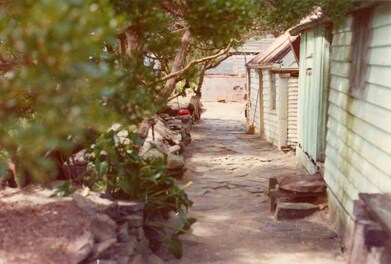

'Main Street', Shack Bay

'Main Street', Shack Bay Only the light, tide, winds or weather altered the flow of activity. When cold south-westerly winds roared, a gentle wave broke around the point. Wisps of scented smoke rose from the tin and stone chimneys like incense, promising a welcoming place to warm hands and stare into a fire.

Swallows arrived every year to nest under the eaves.

A shell midden on the east side of the creek was evidence that it had been a bountiful and idyllic camping place for millennia.

The largest hut had been cobbled together by Percy Williams and his extended family. He lived in Garden Street and worked for the State Electricity Commission. Alert, energetic and keen eyed, with a native intuitive sense of the land, Percy had stopped using his hut, saying “It’s too busy on the coast now”, and changed his holiday camp to a creek near Licola.

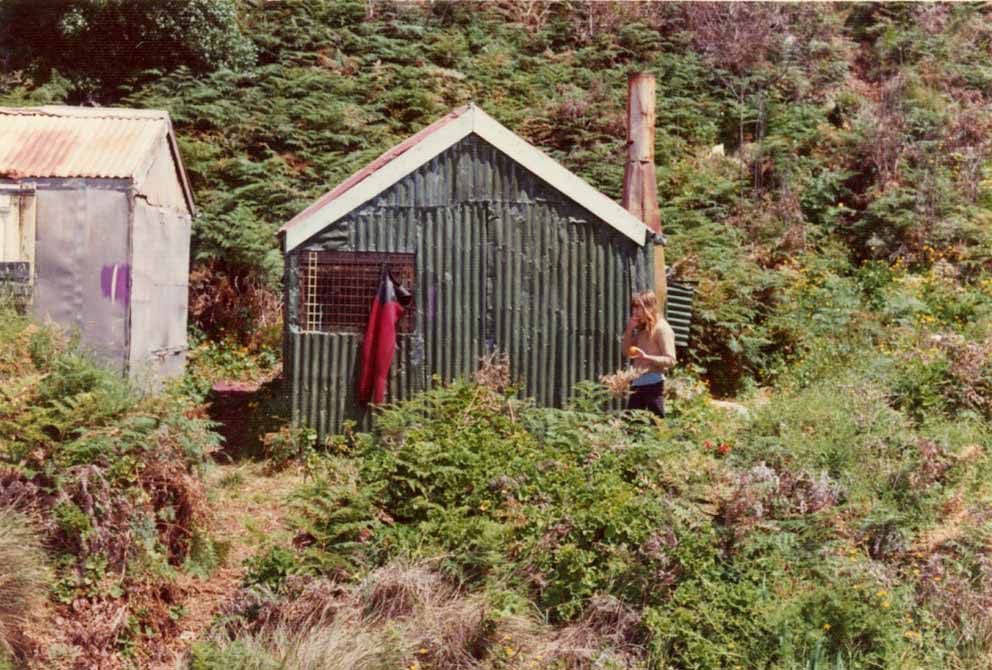

Ken would arrive at Shack Bay in his Kombi van on Friday night, after working in the city as a typesetter at The Age. If he had some spare space left in the classifieds he could slip in a free ad for you. He stayed in the smallest hut, which had been built by George Kiely. It was the standard single bloke’s hut. One room, green tin walls and a red roof. A single bed the length of the south wall doubled as a couch. Opposite was a small open fire with tin chimney, one chair, one fruit box, and a shelf table below the only window which faced the bay.

On a Saturday morning Ken would do shopping for Ethel and anybody else who didn’t want to deal with crowds and commerce, then head back to this free space ready to be filled with serendipitous random wandering, wondering and imagining.

Huts were held more in custodianship than ownership. Most weren’t locked so anybody could stay if a bunk was vacant.

One hut visitor was an anxious looking young man from NSW who was “hitching west”, possibly one of the thousands of draft dodgers on the track for anonymity. How did he know the huts existed? Did the local miners still have union connections in NSW?

Periodic strikes gave miners respite from the gas, dust and fumes of the coal face and a chance to regain their health at the beach. An old bloke said: “Ya know, I never once in my life voted to go back to work. It was just the way things were going for me.”

During the Depression and miners’ strikes, families shared a boat and net at Shack Bay. The primal adventure and excitement of food gathering helped to make the deprivation bearable. An old bloke told me: “In those days we shared a house cow, chooks, gardens, rabbit traps, hand lines, occasional kangaroo, wombat, ducks and fish. There wasn’t really a lot left to buy.”

Lila Williams told me: “It wasn’t easy feeding kids in the old days. The fish didn’t always bite. We ate a tremendous lot of rabbits.” She also grew climbing beans which earned her an instant rapport and friendship with the neighbouring Italians in the crescents of South Wonthaggi.

The coast dwellers were kind to the newly arrived migrants who also had experiences of depravation and hunger. They shared the belief that wasting food was a sin. An Italian day visitor exchanged a bag of onions for a bag of fish. Long after the Depression was over, and the home comforts arrived, they never lost the attitude towards precious resources. Feathers were kept for mattresses and pillows.

Most of the coast hut builders came from South Wonthaggi, where on a still night you could hear the sea murmuring its various moods and tunes. When the September school holidays came, the smell of the sea and the coastal flowers became an irresistible siren call. They held the beach as an aesthetic sensibility beyond religions.

Even after cars became common, some of the old people preferred to walk to the beach. The track to Shack Bay started at the corner of Carneys Road, crossed paddocks, wound through woodlands and skirted wetlands. This slow pilgrimage was part of the ritual, allowing the mind to leave behind the town’s clamour. The thin line of blue sea coming into view was a moment of pure joy.

A childhood place can be the custodian of your early memories. An old bloke with nice clothes turned up to revisit his childhood: times of 20 per cent unemployment and selling rabbit skins to feed the family.

Like other coast dwellers, Norm was a good bushman and camper with strong bronzed hands. Over decades the life of the coast had soaked into him. He never tied up his shoelaces, maybe from all the time spent in bare feet. He was weathered, earthy, steadfast and stoical. Ask him about his experience of the Depression and he answered “We got by”.

He drove an old Vanguard ute and shared an old boat with some mates. He only fished between Flat Rocks and Cape Paterson and only ever used a number four fishhook. Careful observing and listening in nature was his life vocation. He kept detailed records of all his fishing in a battered book. Ron Gilmour, a neighbour from his Broome Crescent days, said “Norm could not swim a stroke”.

With help from friends, she ignored authorities and lived a peaceful life at Shack Bay. The window of her hut looked across the bay. It had a string of cowrie shells draped across it.

With basic needs met, and connected to her place, her desires were focused solely on the wellbeing of grandchildren and those worse off than her. She reminded me of Ma Joad in the novel Grapes of Wrath. “If you're in trouble, or hurt or need - go to the poor people. They're the only ones that'll help - the only ones.”

My last memory of Ethel was a late Sunday afternoon. As the fading winter sunlight moved up the cliff, Ethel was standing on the edge of the rock platform closest to where Kenny was waiting for that one last wave before going back to the city. Ethel yelled, as many mothers of her generation were used to doing, “KENNYYYYY….. YA TEEEEAAAAA’S READYYYYY!!!!”

In the mid `70s the Lands Department put a notice on all the huts stating that if the owners could not produce a current lease they would be demolished.

Like a coast plant clinging to a cliff, with nowhere else to go, Ethel held on to her humble home for as long as she could. Her eviction was traumatic for the whole family. After much anxiety she moved to South Dudley. It might as well have been another country. Like any native with deep roots she did not transplant well. She died in a car accident not long after.

It filled a deep need for me at the time. Arriving at a coastal hut, a school uniform could be rolled up and put out of mind. Like some baptism, the sea cleared the nose, unclenched the brain and restored clarity. Time stretched; thoughts, movements and actions flowed naturally and the boundary between self and the natural world disappeared.

When the wind and sea stop, the deep stillness can be an almost spiritual experience. There were moments of unconscious splendour in the things we did, immersed and absorbed in the light, colour, sound and smell. Watching an eagle or seabird in effortless motion, the jewel flash of a bird through banksias, aimlessly wandering on rock platforms, cliffs and bush hinterland in all directions. We followed the creek inland to what was then a vast manna gum woodland, home to koalas and goannas.

We challenged the elements, took shortcuts up cliffs, tobogganed down the steep grassy hill on sheets of iron. Everything was possible and we felt indestructible. There were moments of wordless communication and understanding between close friends. Events manifested that later left us wondering if they had happened especially for us.

Leaving the huts on Sunday evening and returning to “civilisation” was a solemn process. I would get home late and exhausted, but feeling healed and ready for another round with the modern world.

Those carefree, dreamtime days with the hut people are rich in my memory.

August 27, 2016 - Jim McDonnell was still living in a hut on the coast between Harmers and Cape in the mid-1970s. Frank Coldebella recalls a man attuned to the natural rhythms of life.