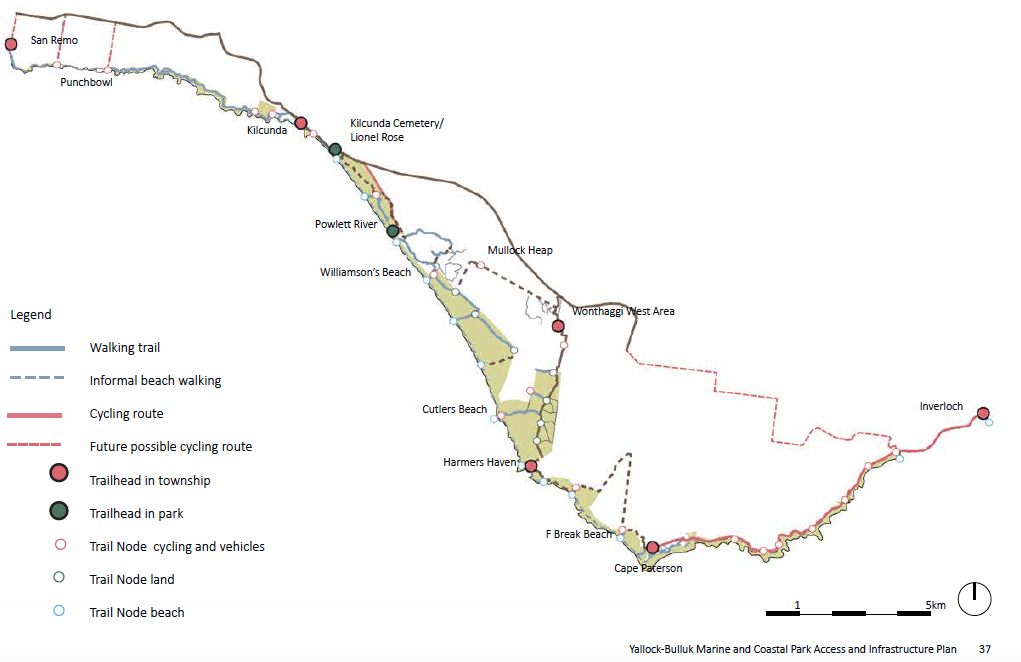

| By Julie Thomas THE push and pull of nature versus development is a recurring theme in our region. As Leticia Laing shows in her article on the proposed Yallock-Bulluk trail, Parks are for Everyone, the escalating impact by people is a continuing source of distress in the community. A walk is good. The designers dream of an iconic walk like Cape to Cape and those at Wilsons Prom. But these are through huge tracts of bushland. Bass Coast is not the Prom. If we are going to have thousands more walkers, it has to be done differently here. A look at the map in Leticia's article shows the desperately thin strip of land which remains for wildlife in this area. If they are disturbed here, where can they go? Nowhere. |

The tramping of more feet – walking on even a simple small path or moving around to construct a boardwalk – gradually destroys thousands upon thousands of these organisms. They are squashed, displaced or smothered by weeds and grasses tracked in on our shoes as seeds. They cannot come back. More leaf litter with its little bugs, gone. Nothing to eat for the birds and the others. They go too.

I have often heard: "What is the point of protecting these beautiful creatures/places if nobody can see them?"

The point is that it's not all about us. It's about morality. A fair go for all animals. It's their world too. Look at the map again. We've taken way more than our share already.

Yes, thousands of tourists visit the Penguin Parade to see wildlife in its natural habitat. But both the transition from beach blankets to viewing platforms and the acquisition/buyback on Summerland Peninsula were designed to keep people OUT of the penguins' way, not to facilitate walking through their habitat. Visitor access is comparable to watching from a lookout, not to a walk through the vegetation.

Penguin Parade infrastructure has been built on previously cleared land and a strong ongoing commitment to restoring natural vegetation on all the other disturbed land has been hugely successful in restoring once declining penguin numbers. That strategy is the opposite of the Yallock-Bulluk proposition to make formal tracks through existing habitat.

The concept of a trail which utilises adjacent, already cleared land makes more sense to me. Despite my anguish back when the desalination plant was proposed, I now applaud the restoration of that area from cleared farmland to a walk-accessible natural park. The project has resulted in new, thriving wildlife habitat and walks which people can enjoy.

The George Bass trail was once cleared land and look at it now.

Some of this will likely be somebody's productive farmland at present. That is another story. This is not a simple fix. But I agree with Leticia that this is an opportunity the Yallock-Bulluk project must seek: restoring vegetation on previously cleared land, making the trail through there and incorporating “offshoot” access to elevated lookouts over the beautiful areas they are seeking to showcase.

Working from a clean slate on the cleared land also allows low-impact access for ongoing track maintenance. This introduces another factor: projects MUST demonstrate that the grants which are sought include provision for the extra staff required, who will maintain this trail along its length for years and years to come. Because, sadly, for every visitor who, given easier access, learns to appreciate the beauty, there are other people who will come simply because it is a secluded spot they can now easily drive to, for dumping rubbish and other clandestine activity.

Countless examples of this, along with eroding tracks and deteriorated infrastructure across the country, show us that ongoing care of these places is often very difficult to achieve, once the fanfare is over, the novelty wears off and the funding dries up in ensuing years.